With its hollow rules, ethical dilemmas, and reluctance to address a lack of transparency and other problems, the Governor’s Council has no clothes

This is the second installment of a three-part series by Jean Trounstine on the Massachusetts Governor’s Council. Part 3 will follow later this month.

Anyone who wants to view a Massachusetts Governor’s Council meeting can visit the State House on Wednesdays and head to Room 360, the council chamber. There, they’ll find a body first established in 1629 that still wields enormous constitutional power to counsel the governor with “advice and consent.” This includes its authority to approve judicial candidates and Parole Board members, as well as to sanction pardons and commutations recommended by the governor and approved by the board.

The council’s dazzling home with high ceilings is just outside the governor’s office, and is filled with portraits of former top officials and a polished table around which the councilors sit. It’s a major part of state history, with the space echoing—for better or worse—a political world that is mostly long gone, but not entirely.

Unfortunately, regulations governing the council seem almost as ancient. Vestiges of how the council operates were enshrined on paper more than two decades ago, in 1993, and stored in the state archives. Archaic language permeates those 31-year-old rules; for example, “Every Councillor [the spelling in the Massachusetts Constitution], when about to speak, shall rise and respectfully address the Governor as ‘Your Excellency’ or the Lieutenant Governor when presiding as ‘Your Honor,’ and shall confine himself to the issue before the Council, and avoid personalities.”

Councilors ratified some new rules in 2023. Most of them are procedural, but overall, they’re not too different from the old ones. While the language of the new rules and the councilor behavior they recommend is somewhat less formal, many directives still seem outworn. In one case, the new version of the above rule reads: “When two or more members raise his or her hands to speak at the same time, the Governor or Lieutenant Governor when presiding, shall designate the Councillor entitled to the floor. Councillors shall confine themselves to the issue before the Council and avoid personalities.”

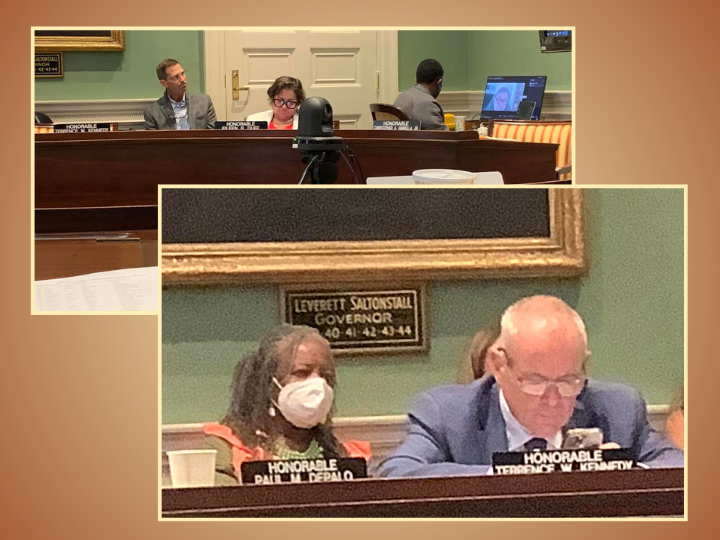

The new rules clearly attempt to deal with unwieldy council members, such as: “No Councillor shall interrupt another while speaking.” But unsurprisingly, such guidelines are often ignored, since outbursts occur frequently.

Activists and other close observers say the new guidance offers nothing to curb what critics call “bad behavior.” Some have even documented these actions on a website, Who Governs The Governor’s Council (a group in which this reporter participates). Offenses include: the incessant use of cell phones by councilors during meetings, and the habit some have of leaving the room while community members are testifying.

There are also no protections against arbitrary rulemaking by the chair. The chair is almost always the councilor in whose district the nominee resides. While one rule permits the public to testify—in person or virtually—that same rule does not specify any time limits for testimonies. As such, it’s common for a councilor who is chairing a hearing to declare time limits on the spot, cutting off those who testify. Councilors also spar openly in spite of rules asking for decorum, which the chair often ignores.

In delving into the body’s poorly-articulated procedures and councilors’ problematic behavior, an investigation that has taken the past six months, we found that few best practices and fewer ethical conflicts are actually spelled out for the council or for the public. With questionable standards and its potential for partisanship, the Governor’s Council operates in a shroud of darkness.

Lack of public records

The new rules from last year shed no light on how to obtain public records about the Governor’s Council. As a result, prison activist Laura Berland ran into roadblocks when she wanted to find out how each councilor voted on judicial nominees.

Massachusetts doesn’t elect judges as voters do in the majority of states—a practice which research finds undermines the rule of law. Here, the governor nominates them and then they are voted on by the council (see Governing in Darkness: Part 1).

Because Berland advocates for New Beginnings Executive Director Stacey Borden, who is currently running for a seat on the council, she felt her candidate could benefit from knowing how councilors voted under former Gov. Charlie Baker. Berland was unsure of who to contact in order to obtain a record of the votes, or if she had to file a formal public records request.

In both the old and new sets of rules that govern the body, Rule #5 dictates: “The Administrative Secretary shall keep a record of the proceedings of the Council in accordance with the law.” However, there is no requirement that the record—i.e. the actual individual votes—be digitized. Throughout the years, hundreds of votes held on hearings have all been recorded by hand. To repeat: in an age when Mass spends millions of dollars a year on hundreds of software contracts, this critical information is still recorded by hand.

Berland called the administrative office of the council and was told that there are not enough people working there to respond to cumbersome public records requests. She also knew that if a request is extensive—and asking for eight years of votes on judicial nominees by the council is apparently extensive—the commonwealth can charge hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars in processing fees. To avoid high costs and still track down votes, Berland was told to do the work herself—at the Governor’s Council administrative office, in the State House, where records are kept in file boxes. And so she went, thumbing through files upon files pertaining to judicial nominees, hand-recording vote results for each petitioner. In order to find out how councilors individually voted, she had to find the votes in each nominee’s file.

It took two hours for Berland to go through one year of judges. While wondering why the council has yet to digitize its voting, we also took matters into our own hands, bringing three interns to the State House to finish the job. They dug through files to record the other seven years of Baker’s judicial nominations, and posted results for the public to view (See more about these votes in Part 1.)

In our months-long investigation of the council, nobody was able to explain why comprehensive vote-recording was not updated.

Berland asked the administrative staff, “Shouldn’t the council have access to technology to record these votes?” The council did not reply.

Ethics and attorneys

Because councilors serve part-time (for $36,000 a year), most have other jobs. And because the work of the council involves familiarity with the judicial system, parole, and other aspects of the criminal legal system, the majority of those who compete to be councilors are attorneys.

Some say it helps for a councilor to be an attorney, particularly in vetting judges. Others say the appearance of a conflict is almost certain to arise when a councilor/attorney argues a case before a judge whose nomination to the judiciary they had previously voted for—or against.

In the new rules, there is no mention of the ethical issues that a councilor can face, particularly when that councilor is a practicing attorney. We wanted to understand if there are such issues in play, and sent out a questionnaire to all the current councilors to get some insight, asking questions about how they handle disagreements, conflicts of interest, and ethics.

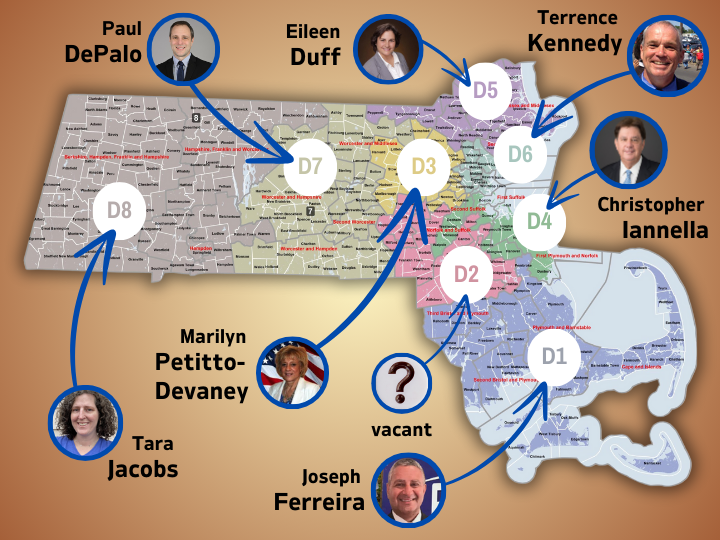

At present, four of the seven councilors are lawyers (one seat is vacant). District 6 Councilor Terrence Kennedy is a criminal defense attorney and former prosecutor; District 4 Councilor Christopher Iannella does personal injury law; District 1 Councilor Joseph Ferreira does general practice and personal injury law, and is a former prosecutor; District 7 Councilor Paul DePalo represents workers and labor unions and does education law. District 3 Councilor Marilyn Petitto-Devaney, District 5 Councilor Eileen Duff, and District 8 Councilor Tara Jacobs are not lawyers. (We look at council members in more depth in Part 3 of this series).

Petitto-Devaney was the only councilor who responded to the BINJ questionnaire. We asked: We have looked for written ethical guidelines for the GC. Why are there no ethical issues and rules for such put in writing for the GC? She answered, simply, that councilors, like all state employees, must complete a “Conflict of Interest” form, with questions about whether one’s work for the commonwealth is compromised. Petitto-Devaney did answer our question about why ethical issues were not addressed while writing the 2023 rules.

The councilors who are attorneys did not weigh in on why ethical issues are not spelled out.

Recusals and other ethical dilemmas

Without responses to questions about ethical issues from the current councilors, we turned to those who previously served in these roles. Thomas Merrigan, an attorney who we interviewed for this series (see: Part 1), was elected to the council in 2006. Prior to winning that position, he was a district court judge for 12 years and told us that, at the time he started on the council, he was uncomfortable appearing before judges he had voted on—even though “no one paid attention to it.”

In a phone interview, retired Judge Jay Blitzman, a law professor and former first justice of the Middlesex Juvenile Court, explained the judge’s responsibility in this situation. He clarified that the question isn’t just whether the councilor/attorney is comfortable, but whether the lawyer and party on the other side of the case is comfortable. The concern then becomes: Could a councilor/attorney be getting preferential treatment from a judge based on approving his or her judgeship? And, Could a future vote for a judge also seal preferential treatment for a councilor/attorney when he or she appears in court?

“It’s a parallel to Judge Aileen Cannon who [Donald] Trump appointed to be a judge,” Blitzman said. Referencing the controversial federal judge who recently dismissed the former President’s classified documents case, he added, “Should she hear a case involving him? It has the appearance of impropriety—and the question has been, Should there have been a motion to recuse?”

According to the Massachusetts Code of Judicial Conduct, judges must recuse themselves when any appearance of impropriety or conflict of interest causes concern. To clarify this, I asked Terrence Kennedy about appearing before judges he’s voted on. Kennedy has been on the council as a practicing attorney since 2011, and in a phone interview said, “A lot of judges recuse themselves from my cases.”

The main issue appears to be that judges want to avoid the appearance of favoritism, while at the same time, they can feel pressured when councilor/attorneys appear before them. In a phone interview, attorney Daniel Medwed, a law professor at Northeastern University, said a “judge is not going to want to antagonize someone, especially if he wants to move to another judgeship.” That means he either recuses himself, or appears to be subject to influence in terms of his decision.

The conflict of interest issue has been raised before. In 2018, the Boston Herald published an opinion column with the headline, “Law allows attorneys on Governor’s Council to face judges they voted on.” This reporter went down a rabbit hole to find this law, and discovered that former Councilor Merrigan had been its instigator.

As Medwed noted in our interview, Massachusetts has an “anti-bribery” law for employees. It was on the books in 2006, when Merrigan began his stint on the body, and the new councilor noticed some exemptions in that law which would apply to legislators who are also lawyers. In other words, it wouldn’t be illegal to practice law outside of their job as an elected Mass lawmaker.

Merrigan realized that the words “governor’s councilor” were not specifically included in the language in that statute, and recently told me that he wanted to change the law to feel protected as a member of the body. “I contacted my legislators at the time to amend the statute,” he recalled. “Sen. Stan Rosenberg and Rep. Chris Donelan were able to get the words ‘executive council’ added to the statute.”

The legislature passed An Act Relative to Members of the Executive Council in 2007. Merrigan’s interpretation: it allowed him to practice in front of judges he had voted on.

Gov. Baker weighed in on this issue in 2018. After he discovered two members of the Governor’s Council—including current member Christopher Iannella—were advertising that they were councilors on their professional websites, the governor told the Herald, “… it does create an appearance issue.”

Currently, the site for Councilor Paul DePalo’s firm mentions his elected role, as does the law group of Councilor Joseph Ferreira, and that of Iannella, whose firm features a dedicated page about the Governor’s Council linked from his bio.

In one paragraph, Iannella’s site addresses the approval process for judicial nominees: “This includes all Department of Industrial Accident administrative judges and administrative law judges, who preside over workers’ compensation matters, as well as the District and Superior Court judges who have jurisdiction over a variety of cases, including personal injury lawsuits.” The links forward to pages on the Iannella & Mummolo site for those areas of practice.

Is it ethical for a councilor/attorney who is voting on judges to advertise it on their website, where they’re seeking clients in their personal law practice? As Baker put it, “In my perfect world, I’d rather have them not do that . . . But I don’t think there’s anything I can do to compel them to change that.”

More transparency needed

There are no written rules addressing when or if a councilor/lawyer should or should not self disclose when appearing before a judge he or she voted on. And while I asked all the councilors who are lawyers to weigh in on this issue, none responded.

Interpreting the current statute is not easy. A legislative aide who asked to remain anonymous told me the law “prohibits a state employee from ‘prosecuting any claim against the commonwealth.’” Here’s how they put it: “Imagine that there is an attorney who works for a state agency. The Environmental Protection Agency, for example. And that attorney also practices private law on the side. The attorney cannot sue the Department of Correction for prisoner abuse.”

With the words “executive councilor” added in 2007, the law permits a councilor to sue the commonwealth, the aide told me. But according to Medwed, “because the statute focuses on compensation, it does not seem to address more subtle forms of favoritism, like bias.” The Northeastern professor said that based on his reading, the statute doesn’t affect whether a councilor/attorney can appear before a judge they voted upon. Another lawyer, speaking anonymously about the statute as a way to justify such an action, said, “That would never hold up in a court of law.”

As far as we could find, there has not been such a legal test.

Considering the stakes, Judge Blitzman suggested, “In the spirit of transparency, there should be a requirement for councilors who appear in court to disclose whether or not they’ve weighed in on a judicial candidate.” The former Middlesex Juvenile Court justice said such a requirement is only fair for opposing counsel, and pointed out that judges depend on the councilor in their district when they are nominated to appear before the council: their councilor walks them through the process, and “strategizes” with them before the hearing.

Councilors have an obligation to “put this on the record” as well, Blitzman added. “There should be a rule in terms of fairness,” he said, “a procedure which requires disclosure.”

Mountains of unclarified ethical issues

Another open question that has ethical implications: Is it a conflict of interest for councilors to vote on a governor’s nomination when that nomination is for a colleague on the council? The Governor’s Council’s 2023 rules do not speak to that. I also contacted the Massachusetts State Ethics Commission, and received no answers from them either.

Councilor Petitto-Devaney has adamantly stated that she believes it’s unethical to vote for “a sitting colleague on the Governor’s Council” when appointed to a position by the governor. If this rule had been spelled out, political connections might have been questioned more vigorously when clerk-magistrate candidates with close ties to former Lt. Gov. Karyn Polito, for example, landed lifetime appointments.

Ethics researchers at the University of Santa Clara define patronage as “giving public service jobs to those who may have helped elect the person who has the power of appointment.” In a paper on cronyism, they explain that patronage may “undermine the public good” because it means you’re not hiring the most “competent” candidate.

In 2019, Shrewsbury Police Department Lt. Joseph McCarthy Jr. was approved by the council to serve as clerk magistrate of Westboro District Court. He had previously coached Polito’s son in youth football, as had another Shrewsbury resident who was appointed as associate justice of the same court. Also in 2019, another clerk-magistrate job went to a college friend of Polito’s.

Members of the Governor’s Council complained, yet the nominations sailed through. In another case where there was pushback, Councilor Petitto-Devaney raised a ruckus in 2019 when Jennie Caissie, a sitting councilor at the time, was nominated for a clerk-magistrate position. Councilor Robert Jubinville also protested; he and Petitto-Devaney voted against her nomination, in part because of her political ties to the Baker administration. The final vote was 5-2.

Three years later, ironically, Jubinville threw his own hat into the ring to serve as a clerk-magistrate while he was still a sitting councilor. Following his own hearing before the body on which he was elected to serve, only Petitto-Devaney voted against him. Clerk magistrates are full-time positions; Jubinville’s starting salary on the bench: $174,532 a year.

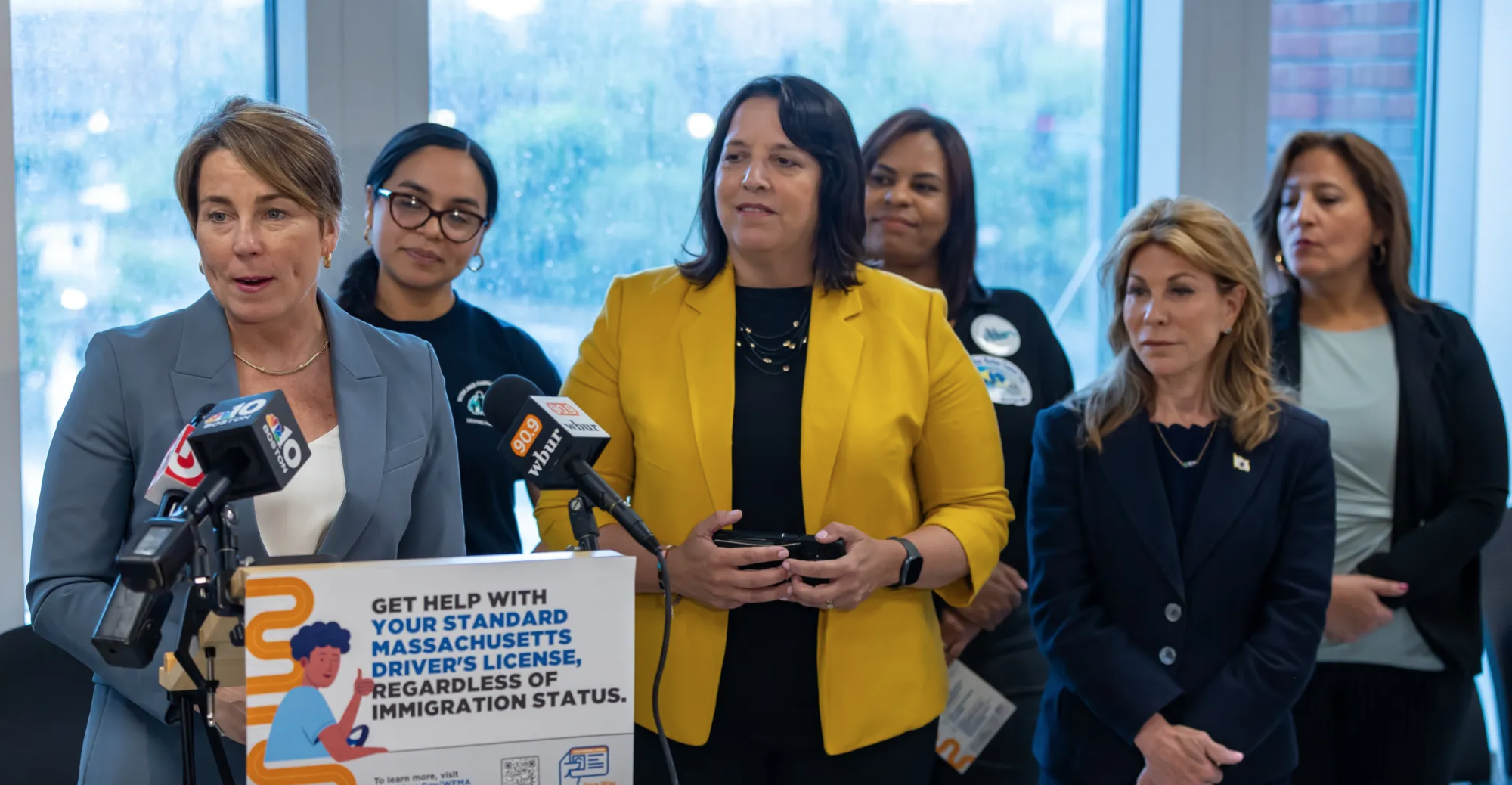

More recently, questions emerged in the press this year when Gov. Maura Healey nominated her former romantic partner, Justice Gabrielle Wolohojian, to the Supreme Judicial Court.

Councilors differed in their views of the appointment. District 8 Councilor Tara Jacobs wondered aloud about the ethical issues of nominating Wolohojian. At the February council hearing for the nominee, Jacobs called her past relationship with Healey “the elephant in the room.” Councilor Kennedy, however, said, “I have never asked a nominee anything about their personal life and I never will.”

Six members voted in favor of Wolohojian, with Jacobs the lone vote against the appointment. The question then became: What is the relevance of a judge’s personal life in terms of his or her nomination to the court? And, Is it ethical for the council to consider “personal life?” One might also ask, Is a comment about one’s personal beliefs the same as a comment about one’s personal life?

In a December 2023 hearing for Elizabeth Dewar to serve as associate justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, Kennedy said he believed standing against the death penalty was a “litmus test for nominees.” When Dewar did not reveal how she would vote if that issue came up, Kennedy added, “I respect your answer that you cannot say 100% . . . how you would rule, but it’s pretty clear your personal views will affect your decisions as it does everybody.”

Such circumstances summon the question: Should the judgment of nominees, both in terms of their personal life and personal beliefs, be spelled out more clearly? Couldn’t that help councilors-to-be—and, by extension, the public—see how the Governor’s Council specifically evaluates nominees?

Some councilors have even criticized candidates for their beliefs. When attorney Joseph Berman said at his hearing that he was proud of his work as a lawyer defending a prisoner at Guantanamo Bay, former Councilor Caissie said, “It was simply done to pad his resumé.” Because of this and other council member concerns, Berman was not approved for a judgeship.

In spite of rules which call for civility, councilors also attack each other beyond ethical organizational norms. In one hearing, Councilor Eileen Duff snarled at Petitto-Devaney, “I wish you’d get your facts straight.”

When Petitto-Devaney fought to keep livestreaming of council hearings after the pandemic, other councilors tried to move the hearings offline, out of the public view. According to Mass Lawyers Weekly, the coverup was clear: They reported that the Governor’s Council blamed Gov. Baker, only to be assured by the governor’s office that its video equipment was readily available.

Following pressure from outside groups including the ACLU, the Disability Law Center, League of Women Voters of Mass, and the Massachusetts Newspaper Publishers Association, livestreaming resumed. As Mass Lawyers Weekly noted, “A Massachusetts government body wanting to do its business without anyone watching is hardly unique, sadly.”

The council now has a YouTube channel, and recordings from hearings are stored online and searchable from the Governor’s Council website. However, videos regularly only show the nominees and those who testify before them, and not the councilors asking questions. In the opinion of advocates and others, this is another stealth move that compromises transparency.

Per an administrative staffer at the Governor’s Council who spoke for this article, the majority of councilors felt livestreaming that focuses on nominees is “advantageous to public viewing.” But they disagree about particulars. In videos of council hearings, for instance, you can hear Petitto-Devaney claiming the cameras are only focused on petitioners.

And those are just the ethical issues they face as a group. As individuals, there is even less clarity around permissible behavior. Next, we will take a closer look at the stars of the show.

In Part 3, we consider the personalities that make up the council, examine solutions that advocates have suggested to reform the body, and look at the current district races heading into the September primary and November election.