Who are the Massachusetts governor’s councilors? What professional baggage do they bring to the body? And can this motley crew stumble toward reform?

This is the third installment of a three-part series by Jean Trounstine on the Massachusetts Governor’s Council.

Though an obscure body, the Massachusetts Governor’s Council wields enormous constitutional power. The eight-member council, established in 1629, votes on judicial, Parole Board, and other court nominations from the governor. It also approves or disapproves her recommendations for pardons and commutations, most sanctioned by the Parole Board.

Since 1854, a seat on the Governor’s Council has been an elected position, but most residents have no idea who their councilor is. It’s common for incumbents to run unopposed, like in two of the eight districts in the current election cycle.

Critics who want to see the council abolished call it a rubber stamp for the governor. Among other observations, they note how councilors approved all but one of former Gov. Charlie Baker’s 350 nominees in an eight-year stretch, with only five people withdrawing their nominations when they realized they would not be approved. The People’s Parity Project (PPP), a coalition of law students and attorneys who want a more democratized legal system, have asked why councilors don’t scrutinize nominations more carefully.

During six months of research for this series, we have also heard from some stakeholders who claim the council can be salvaged. A number of them said that voters should impugn the current councilors and implore them to represent their constituents’ interests. Others put more weight into reforming council practices than into changing the cast of characters. And yet another faction wants to change representation, arguing that the way Massachusetts residents vote for councilors makes no sense. They point to how there has been only one person of color on the body in its 400-year history.

Some proponents of the council are engaged in educating the public about the current race. (The primary is Sept. 3 to determine who competes in the final election on Nov. 5.) Only if challengers defeat incumbents, they say, and bring in new blood, can the council regain its intended independence.

What would it take to change public perception? And, what proof is there, if any, that the Governor’s Council is not what political blogger Charles P. Pierce once called “a relic of colonial government that now functions as a job-lot store for second-to-fifth-rate politicians?”

In short, what would it take to truly reform the council?

The “independent” councilors

With the Governor’s Council being the last gateway to the state’s judiciary, government watchdog groups say it is important to scrutinize candidates closely. With such scrutiny comes the question of who is willing to say no to the governor’s choices, whomever that governor may be.

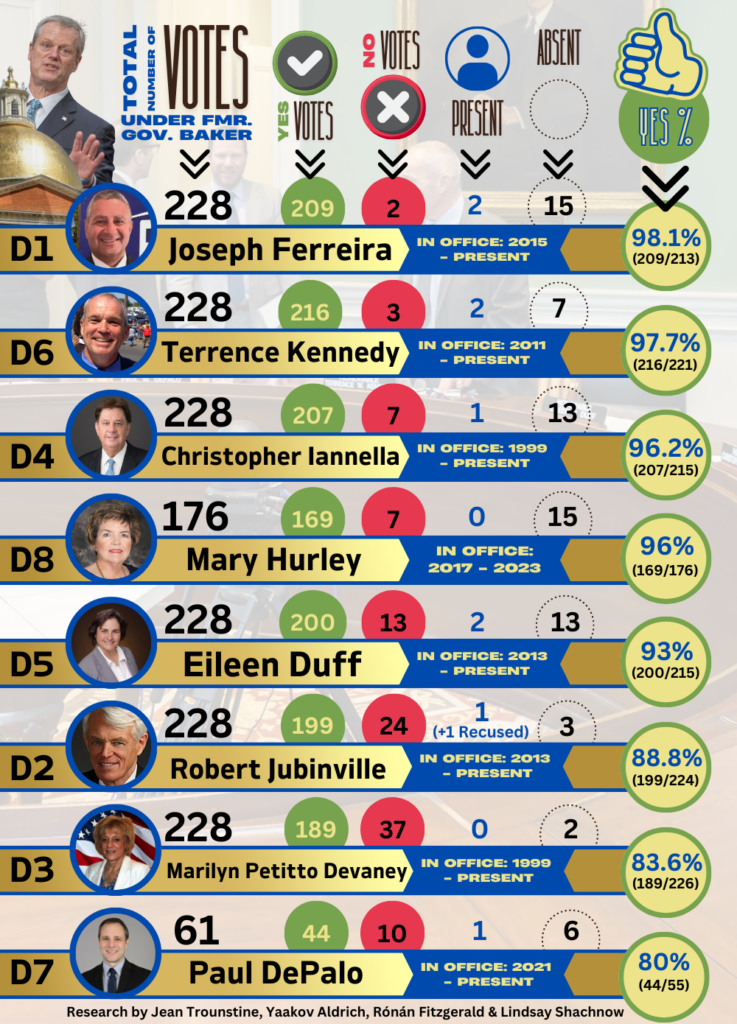

In our deep dive, we found that one way to measure the independence of current council members—i.e. how much scrutiny they put into their consideration of nominees—is via their voting records.

The councilor with the most independent voting record during Charlie Baker’s tenure was Paul DePalo of District 7. In other words, he voted least with the former governor on nominations ranging from judges to court clerks to Parole Board members—at 80%.

DePalo was first elected to the council in 2020. At the time, he called himself “a new voice” and gave supporters yard signs with the slogan “Judges Matter.” DePalo said on his campaign site in 2024 that he was proud of his “no votes,” and recently remarked that he pores over candidates’ applications. In an email exchange provided for this story, DePalo wrote about his approach, “I certainly recruit and coach applicants through the process, as well as advocate within the Governor’s Office [to her] Legal Counsel.”

While DePalo has the most independent voting record, District 3 Councilor Marilyn Petitto-Devaney comes in at a close second, with 83.3%. Petitto-Devaney has been criticized in the press for a number of issues ranging from dubious endorsement claims, to fights with other councilors, an alleged assault with a curling iron, and questions of who threw a dime at whom after a council meeting. She has also been excoriated for her ignorance on issues and for allegedly fiddling with someone else’s mail.

In spite of criticisms, Petitto-Devaney, a non-lawyer who was first elected to the council in 1998, has fought off challengers, and managed to maintain some independence in her voting record. As we covered in the second part of this series, she was largely responsible for pushing the council to livestream after COVID, while some of her colleagues had tried to end that practice.

One of Petitto-Devaney’s harshest critics has been District 5 Councilor Eileen Duff, who once told a reporter that she “seriously think[s]” her colleague “is mentally ill.” Also a non-lawyer, Duff voted with Baker 93% of the time. She is not running for reelection, but is instead leaving the council to run for Essex County register of deeds.

District 8 Councilor Tara Jacobs was elected to the council in 2022, and does not have a voting record on Baker’s nominees. A non-lawyer as well, she bills herself as the social justice voice of Western Mass, saying she wants to “dismantle systemic injustice.”

Jacobs recently took a stand that separates her from the mainstream. In February 2024, she was the lone councilor to vote against Gov. Maura Healey’s second appointee to the Supreme Judicial Court, Gabrielle Wolohojian. She stated her perception of Wolohojian: “She intellectualizes the marginalized community’s struggle in a way that feels very much a bubble of privilege and detached from the struggle itself.”

While a few councilors vote with more independence than others, some still say the council has outlived its shelf-life because of the perception it is glued to the governor’s hip.

Stars of the show

The councilors who voted most with Baker are three attorneys, and they are some of the longest-serving members: 10 years (Joseph Ferreira); 14 years (Terrence Kennedy); and 36 years (Christopher Iannella). Their voting records signify a lack of autonomy from the previous administration. (As we covered in the first installment of this series, there is not yet enough data from the tenure of incumbent Gov. Healey to meaningfully analyze those votes.)

District 1 Councilor Ferreira voted with Baker 98.1% of the time, while Kennedy from District 6 and Iannella from District 4, respectively, cast 97.7% and 96.2% of their votes in support of Baker’s choices.

As for the results of this kind of lockstep approval, it leads to what the People’s Parity Project describes as a path to installing judges from big corporate firms, instead of ensuring there are “pro-people judges” (see Part 1). As of this writing, all eight judges on the commonwealth’s Supreme Judicial Court are former corporate lawyers, what PPP calls “a bench that is out-of-touch with the needs of the state.”

Councilor Ferreira’s law firm’s website notes that he’s a former police officer who earned his law degree from Southern New England School of Law in 1992, and was elected to the council in 2014. In an interview from when he first joined the council, Ferreira did not specify why he wanted the job, only that it opened a new chapter in his life, and that, if he was asked to run for district attorney, the councilor “would give it deep and careful consideration.”

Sandy Sweetnam, a member of the all-volunteer group called Who Governs the Governor’s Council or WGCC (in which this reporter participates), has attended more than 10 hearings in the past year, and has many first-hand observations. According to WGGC, Ferreira, like most of the councilors, “grandstands” on certain issues to make points he wants to hammer home to nominees. In an email interview for this series, Sweetnam wrote, “Ferreira frequently mentions his background as a ‘cop’ and mentions the Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Commission which he says reported racial bias in sentencing. He claims as a result [of their report] cops are frightened to make arrests.”

Sweetnam has identified “pet issues” for all of the councilors. Criminal defense attorney Terrence Kennedy, for example, tells attorneys who want to be judges that there are too many “court procedures which make [life] difficult for private practice attorneys.” Councilor Iannella, meanwhile, often comments on custody issues when interviewing judges at hearings. In her report from a December 2023 hearing for a probate and family court judge, Sweetnam emphasized Iannella’s focus on custody arrangements and equitable sharing.

He mocked [the candidate] and became increasingly rude: “Would you make things 50-50? I haven’t got that from you yet” he said. She responded “It would be 50-50 if I can.” He barked, “Why can’t you, you are the judge? Is that what your heart says or are you trying to please me? Would you have the courage?”

The lawyer

Councilor Kennedy was elected to the body in 2010 and has defeated challengers ever since. He comes from a political family; his father, John P. Kennedy, a former state rep. from Everett, served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1958 to 1964.

Kennedy was supported in his reelection bid in 2020 by then-Attorney General Maura Healey. That year, close allies to Gov. Baker contributed to a Super PAC (political action committee) to support mailings for Kennedy to the tune of $34,770. At the time, Scott Ferson, a Democratic consultant and strategist, suggested Baker was “kicking the tires on a third term,” hoping for Democratic support.

Heading into this year’s election, Kennedy raised more money than for any of his previous bids; according to the Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance, as of July 31, he had $130,458 on hand. In nearly 14 years in office, Kennedy’s campaigns have taken more money from attorneys than from any other occupation—in excess of $143,000.

Philosophically, Kennedy has said that members of the Governor’s Council should be attorneys. He told a reporter in 2016, “It’s important you have someone in there who knows what they’re doing and is qualified to do it and is a lawyer.”

In his own private legal practice, Kennedy has defended high-profile political figures accused of—and, in some cases, found guilty of—sexual crimes. Those include former state Sen. James Marzilli, who pleaded guilty to accosting women, attempting to commit indecent assault and battery, disorderly conduct, and resisting arrest. Kennedy also represented a former transit cop accused of sexual assault, a man charged with rape who is the brother of a former big-city mayor in Mass, and a North Shore police chief who was fired for “destroying and tampering with evidence,” and charged with “disturbing allegations regarding certain relationships with women.” Speaking to the press about the latter, Kennedy called the investigation a “witch hunt.”

We attempted to contact Kennedy to ask about his defense of these clients, but the councilor did not reply.

When Kennedy first ran for the Governor’s Council in 2010, he said, “Justice for the accused and justice for the victim depend on judges who both understand the law, and recognize that fairness and impartiality are crucial to maintaining the public’s support and confidence in our justice system.” To that end, the councilor recently supported the historic blanket “megapardon” granted by Gov. Healey for misdemeanor pot convictions. Kennedy said the commonwealth should do more to actually reach those who were unnamed: “Most people that have a marijuana conviction don’t know what’s going on in this room today, and never will,” he said at the hearing.

The third wheel

Like Kennedy, Christopher Iannella, cofounder of the Boston-based Iannella & Mummolo law firm, comes from a well-connected political family. We also asked him to comment on this and other issues relating to his years as a councilor but received no response.

Iannella’s brother and sister have both been politically active and employed in government jobs, what the Boston Globe called “a family business.” In 1997, reporter Frank Phillips wrote that former Gov. Mitt Romney took aim at possible improprieties in the family, insinuating that Christopher had lobbied to get family members jobs. Romney called it political “patronage.”

Iannella is the longest-serving councilor. He was first elected to the council in 1984, then defeated in 1990 by Michael M. Murphy, the only Black councilor to ever serve on the body. Iannella regained his seat in 1993, and has served ever since. In one race, he was accused of “wrongly gaining access to absentee ballots” by his opponent in a vicious battle that Iannella ultimately won by 26 votes.

Our investigation found more than 40 cases involving Iannella as a party (or a public administrator) in Suffolk County Probate and Family Court, 15 cases in Superior Court, and several in federal court. As we covered in Part 2 of this series, councilors who are lawyers have opportunities of appearing before judges they have voted on or will vote on; in those cases, more possible ethical issues can arise.

This past April, after a debate with two challengers vying for his council seat, a reporter from the Patriot Ledger asked Iannella “if his law practice ever brought him before a judge he had confirmed on the bench.” The incumbent responded “that has never occurred in [my] time on the council.” Iannella added, “In all my years on the council, I’ve probably been in court representing two different people … I don’t go to court.”

However, one 2018 case in which Iannella and his firm were among multiple co-defendants reflected on his role as a councilor-attorney. In the complaint filed in Suffolk Superior Court, another attorney accused Iannella of being a “deceptive bully,” and of “rascality” in his practices to get paid by a former client. Iannella disputed legal fees related to the case, and in an email to the parties involved, an administrative judge who heard the case expressed concern about “making a decision about the attorneys’ fees” and over “seeking future reappointment to a judgeship for which Iannella is a sitting Governor’s Councillor.” In other words, the administrative judge was worried about what might happen if he tried to move to another court and would have to appear before Iannella, who was a party in this case.

There is no public information available about how this case was eventually resolved.

How about an informed electorate?

Attorney Harry S. Margolis ran for Governor’s Council against Marilyn Petitto-Devaney in 2012, and lost. Years later, he posted on his law firm’s website, “Few people know anything about the Governor’s Council because it gets little publicity.” Without the public knowing who they’re voting for, Margolis argued, it is an “undemocratic” body.

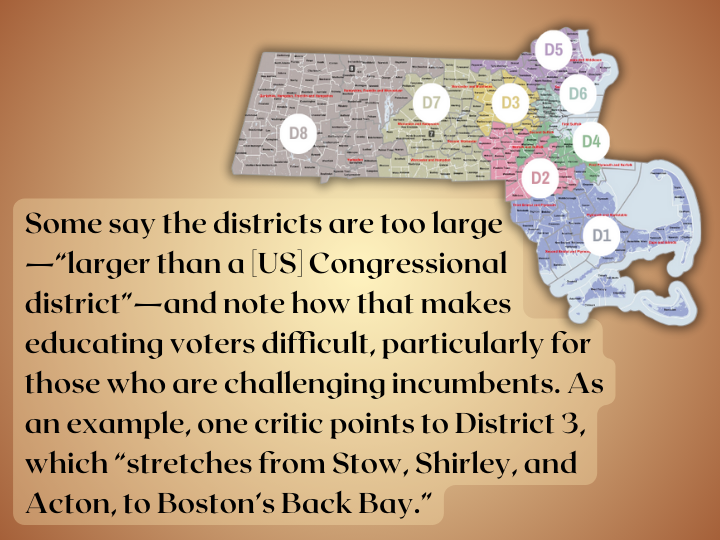

Margolis, who works with WGGC, suggested that the districts are too large—“larger than a [US] Congressional district”—and said that makes educating voters difficult, particularly for those who are challenging incumbents. As an example, Margolis points to District 3, which “stretches from Stow, Shirley, and Acton, to Boston’s Back Bay.”

Congressional districts can be reapportioned every 10 years, according to state law, but Peter Wagner, executive director of Prison Policy Initiative, explained in an email that it is not clear about how Governor’s Council districts get changed.

Former District 8 Councilor Michael Albano recognized that the large districts make it hard to communicate with constituents. While in office, he held meetings to educate the people of Western Mass and get their input on nominees. “Not everyone can get to the State House on a Wednesday,” he said in a phone interview for this article.

Albano put the transparency bug in the ear of Councilor Tara Jacobs, a successor in his district. She convened a similar gathering so that people could learn about Deepika Shukla, who recently was approved by the full council to be an associate justice of the Superior Court. Jacobs plans to continue having such local convenings, while Albano noted that outgoing Councilor Eileen Duff also hosted similar events. These are the exceptions, however, as most councilors do not prioritize informing the public.

Albano said he feels strongly that the Governor’s Council should be subject to the Open Meeting Law, which requires public bodies to open most meetings to anyone who wants to attend. Currently, councilors can meet behind closed doors with nominees, and are not required to share notes from their meetings with constituents, or for that matter, with other councilors. Albano also said that “councilors should have a set of rules,” and that the body should issue reports to constituents about council activities and positions on nominees.

In an interview for this article, David Harris, a former executive director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute of Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, said he wants to carry Albano’s point even further and see the council “anchored in community justice.” In a phone interview, Harris, who is one of WGGC’s founding members, explained that the current council is not “representative in a democratic way—that speaks for the people.” He wants to see Mass residents “demanding representation,” and “those who have been excluded raise their voices in terms of policies that they want enacted in their community.”

The council is another example of systemic racism in our society, said Harris, and it’s not surprising that only one councilor in centuries has been a person of color. “Blacks need allies to make the changes that are needed to create a society that’s just for everyone,” he said. “By influencing the Governor’s Council, they can make changes with judges and parole board members.”

Harris also emphasized the importance of monitoring what councilors are doing, how they are voting, and why. “It’s appalling to me that I have never received even one email from my governor’s councilor,” he said. He added that councilors should “have more public events in the community and seek input from community members,” suggesting that kind of accountability could “reinvent the role of the Governor’s Council.”

Do elections matter?

The commonwealth’s elections process has been less than helpful in bringing the council out of the shadows. Voters take note: the Massachusetts ballot does not say the words “Governor’s Councilor,” but instead only has the word “Councillor” (the original spelling from the Massachusetts Constitution) on both the primary ballot in September and the election ballot in November.

This past session, state lawmakers considered legislation that would add the word “Governor’s” to the ballot. The bill had a hearing, was reported out favorably, and went to the Senate Committee on Rules. As of this writing, no action has been taken.

John Griffin, the managing partner for strategy at Partners in Democracy, founded by Harvard political philosophy professor Danielle Allen to pursue “democracy renovation,” said people mistakenly tend to “equate democracy with elections.” Because governor councilor races are so “low-profile”—scant coverage of candidates, incumbents often win, etc.—he suggested randomly choosing councilors rather than electing them, in the same way we choose juries. Griffin spelled out his idea in a recent blog post, acknowledging it would take years to change the constitution, but concluding that we’d have a far more independent council that is not beholden to the governor.

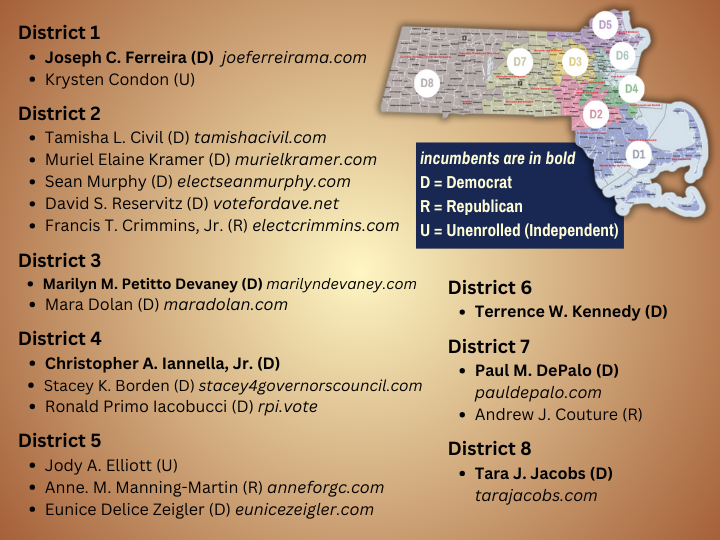

To change the council, some say, change the people, not the process. Others simply want to spread awareness about the obscure powerful body. (The accompanying chart shows the contests (or lack of) in all eight districts.) To that democratic end, League of Women Voters of Massachusetts sponsored a nonpartisan educational forum with WGGC this month to discuss the Governor’s Council in depth. This reporter participated and, with fellow panelists, addressed a number of the issues covered in this “Governing in Darkness” series, including the potential of reforming the council.

David Harris, the former ED of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute, also participated. “This is no longer a position of privilege,” he said. “We must expect, indeed demand, more from those who claim to represent us.”