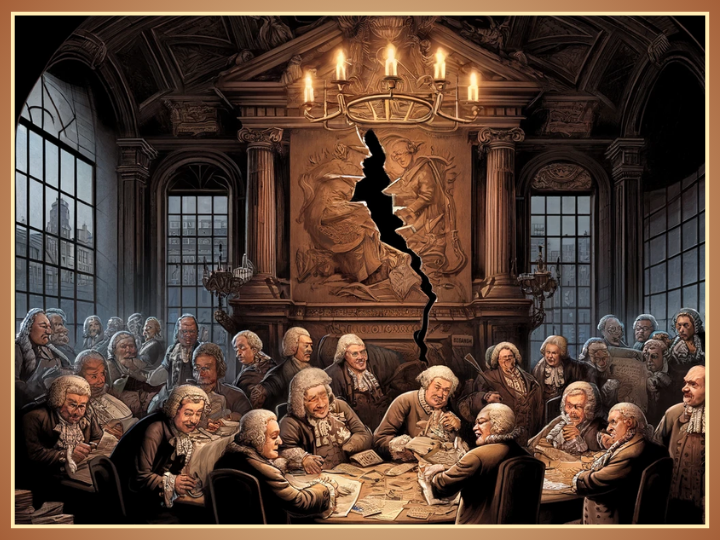

For centuries, critics have questioned whether the Governor’s Council, rife with conflict, should exist. In 2024, is the body obsolete?

This is the first installment of a three-part series by Jean Trounstine on the Massachusetts Governor’s Council. Parts 2 and 3 will follow in the coming weeks.

It’s been called a “clown committee” and a “side show filled with school children.”

Some critics have ominously declared it a “den of patronage,” saying the body simply “rubber-stamps” gubernatorial nominees for judgeships and other important positions.

Others have labeled it a “hock shop,” “dysfunctional,” and an “anachronism.”

We are of course talking about the Massachusetts Governor’s Council, which in many ways works in the shadows but wields enormous constitutional power to counsel the governor with “advice and consent,” including the authority to approve judicial candidates.

We have been investigating the obscure body for six months, unraveling records that only exist in paper files in the State House, delving into history, and scouring news archives. We want to know how the council operates, what’s behind consequential appointments, if constitutionally-required checks and balances are in place, and whether politics plays a role in these important decisions. Our mission: uncover how the council—and the process—produces certain kinds of nominees, and drastically overlooks others.

As the Sept. 3 primary looms for Mass voters, along with the subsequent Nov. 5 general election, and with several council seats up for grabs, this is a deep dive into the workings of a body that remains mysterious despite being around for nearly 400 years.

A dubious past

The Governor’s Council, or the Executive Council as it is also called, has eight elected members from districts across the commonwealth, each serving two-year terms and paid $36,000 annually for part-time work. They meet on Wednesdays and, according to the body’s listed charge, “record advice and consent on warrants for the state treasury, pardons and commutations,” and vote on “gubernatorial appointments such as judges, clerk-magistrates, public administrators, members of the Parole Board, Appellate Tax Board, Industrial Accident Board and Industrial Accident Reviewing Board, notaries, and justices of the peace.”

At one point long ago, the council had much more authority, voting on in excess of 1,000 different jobs appointed by the governor. A lot has changed over 400 years though. According to the citizen watchdog group Who Governs the Governor’s Council (in which this reporter participates), in the age before councilors were elected, the title was originally spelled “councillor” in the state constitution, while one early member, Isaac Royall Jr., was “the largest slave owner in Massachusetts whose family wealth was derived from his father’s slave-based plantation in Antigua.”

Between 1855 and 1964, the Governor’s Council’s record was peppered with impropriety. One well-known scandal centered around Councilor Daniel H. Coakley, who was disbarred in 1922 for, “among other things, extortion.” In a recap of the events on his blog, Mass attorney Peter Vickey wrote that “disbarment did not outweigh Coakley’s connections.” As such, “He was elected to the Governor’s Council in 1932.”

In 1964, with voters up in arms after multiple councilors were indicted on corruption charges, Bay State voters stripped the council of many of its powers. The ballot measure approved that year was intended to stop councilors from taking money or gifts in exchange for helping advance nominees. The body’s constitutional authority remained intact, however, including its role in advising—and consenting—on judges and other gubernatorial nominees.

Looking back on his time in office, in 2004, former Gov. Michael Dukakis bemoaned to an interviewer having “to confirm every single appointment.” At one point during his tenure, the Duke attempted to abolish the body, and famously banished its chambers to a less desirable corner of the State House.

“They had to practically give you permission to go to the bathroom if you were governor,” Dukakis said.

Vetting isn’t always enough

By 1975, Dukakis came up with the idea of what is now called the Judicial Nominating Commission to supposedly remove politics from the process. In its Guide to the Massachusetts Judicial Selection Process manual, the Massachusetts Bar Association writes that the 20-plus member JNC was designed to “identify and invite applications by persons qualified for judicial office,” and to “advise the governor” on appointments for clerk-magistrates and judges. This is all before the governor selects the nominee and sends them to the Governor’s Council.

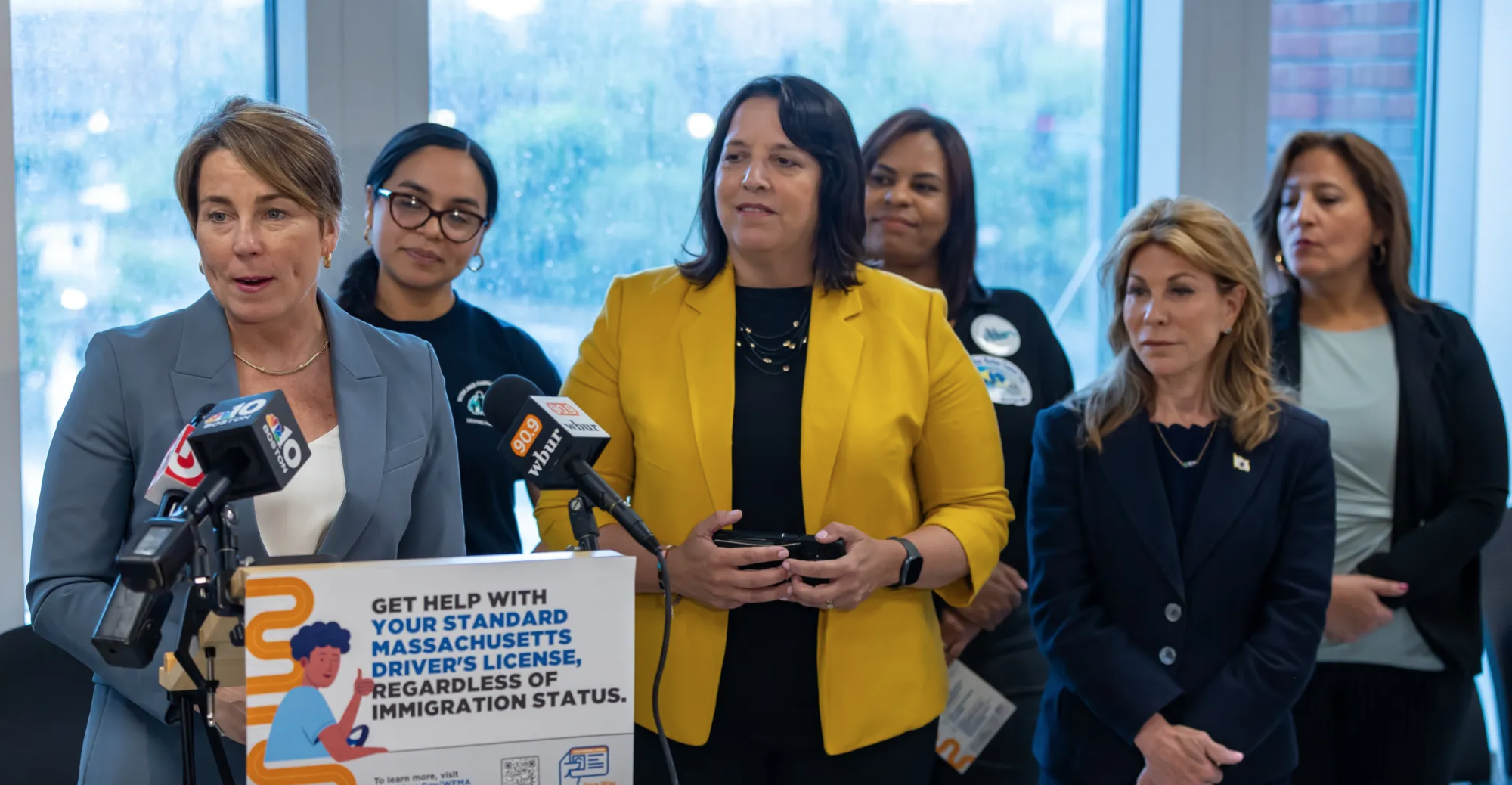

Since then, each governor has put his or her stamp on this commission and appointed their own members. For example, Gov. Mitt Romney insisted that blind review of applications, the first of its kind in the nation, would assure a better merit-based selection process. Gov. Deval Patrick put more members on the commission from the business community, “wanting them to have a seat at the table.” When Gov. Charlie Baker was in office and three Supreme Judicial Court judges were close to retirement, he created a separate Supreme Court Nominating Commission. And while most governors have sat a 21-person JNC, Gov. Maura Healey appointed 27 commissioners, mostly attorneys.

The JNC vetting of prospective nominees is extensive. Candidates meet with members individually and, if successful, must then meet with the whole commission. Interviews with outside sources and attorneys are held to vet the nominees. Then, for candidates who make it to her office, the governor’s chief legal counsel seeks opinions from the Joint Bar Committee on Judicial Appointments, which is composed of lawyers from the various bar associations across Mass.

Healey appointed JNC members last year, about four months after taking office. In the time since, the governor has been criticized by prison rights advocates and others for being slow to nominate judges. On July 11, the State House News Service reported on District 8 Governor’s Councilor Tara Jacobs having frustrations about vacancies in “one out of every seven full-time seats on the Superior Court bench.” Other members of the council joined the chorus, and on July 17, Healey finally announced five Superior Court nominees.

Where do Massachusetts judges come from?

There is still more criticism out there about the way Massachusetts has filled its courts. While data is not yet available for the new administration, critiques of the current bench might serve as a warning. Molly Coleman, executive director of the People’s Parity Project (PPP), a national movement of attorneys and law students, wrote in an email this month: “The Massachusetts state bench is full of corporate lawyers and former prosecutors. This isn’t a coincidence: it reflects a system designed to empower those who have experience representing the powerful at the expense of the people.” The group has flagged similar institutional issues in Arizona, Georgia, and Connecticut.

These observations aren’t new. In 2015, former District 8 councilor Michael Albano took Gov. Baker to task for keeping a statewide commission rather than creating regional commissions, which Albano said would draw attorneys from smaller firms. But Baker stuck with tradition, and Healey has as well.

PPP sent us information from a report due to come out, verifying what we also found in an independent Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism analysis: 60% of Massachusetts judges are ex-prosecutors. According to the group, only 3% “worked as public defenders, representing people accused of committing crimes who couldn’t afford lawyers,” while 2% “worked at legal aid organizations that help poor people in civil matters.” Nearly half (48%) of commonwealth judges are “former corporate lawyers.” As PPP explains, that “doesn’t just mean that they work in a fancy office.” Rather, “These are lawyers at firms that specialized in representing corporations, and they spent a significant portion of their career ensuring that corporations’ bottom lines prevail during any disputes with workers or consumers.”

Coleman added: “The Governor’s Council [should] make it a priority to ensure that the judiciary reflects the values of the people of Massachusetts, not the values of powerful interests.”

That is easier said than done, and it’s hard to see what work is underway to diversify the bench. The Governor’s Council has its own questionnaire for screening judges, but the forms are not available online. Similar to details about rules that govern the body around ethics and transparency, the candidate surveys are hard to come by, and took weeks to obtain for this article. Like so much about the council, the lack of transparency results in confusion for reporters and misinformation for the public.

Some members have noted that the labyrinthe process puts them in the passenger seat. When Baker first came into office, District 6 Councilor Terrence Kennedy complained to the State House News Service that the JNC “encroaches” on the Governor’s Council. “We only see the end result,” he said.

It’s true that councilors, like the rest of us, are not privy to the inner workings of the JNC. But even if they are excluded from the seminal vetting process, they still have the final say. How they make decisions is part of the opacity.

Abolish or reform?

The first step for BINJ was to go behind the scenes and find out how the councilors vote. Our idea was that the record would inform us about each member and we would proceed from there. We were not expecting to discover smoking guns like exchanges of cash for votes, as one governor accused his councilors of nearly a century ago. Rather, we wanted to see if members are performing due diligence.

Their voting records were the first measure. We began by picking through judges’ files, in the process researching how councilors weighed in on nominations during the eight-year administration of Gov. Charlie Baker. The resulting table includes all the kinds of judges—from superior to probate, district to accident, juvenile to housing, etc.—along with the councilors’ votes. (Some nominations where the votes were close are bolded in the document.) According to the data, a number of councilors voted in lock-step with Baker most of the time; others did not, and we will address the discrepancy in later parts of this series. The general finding, however, is that the “rubber stamp” description might fit after all.

Analysis of the records of councilors during the Baker administration show that overall, councilors approved Gov. Baker’s choices 80% of the time. Individually, three members most often backed Gov. Baker: Joseph Ferreira from District 1 (98.1%), Kennedy (97.7%), and Christopher Iannella from District 4 (96.2%).

As a group, this so-called independent body—after all the vetting by the JNC, Joint Bar Committee, and governor’s legal team, plus the private and public interviews conducted by the council—approved 350 of Baker’s nominees, with five people withdrawing their nominations, and only one negative vote. That includes the approximately 228 judges we could locate in the files.

All of which begs the question that observers have asked for ages: Does the Commonwealth even need the Governor’s Council?

Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, which has always advocated to “change the people not the process,” threw its hands up in 2022 and called for a replacement to the Governor’s Council, suggesting “convening a study committee” and examining what other states do.

But some still sing its praises. In an interview for this article, former Governor’s Councilor Thomas Merrigan said, “I think the council is very relevant and necessary, an important check and balance on the executive branch.” An attorney who also served as first justice in the Orange District Court from 1990 to 2002, he added, “The governor shouldn’t be making appointments unilaterally. Some states do it by having one of the legislative branches act on judicial nominations, but that would be even more politicized—they would have a lot more to horse trade.”

Still, Merrigan recognizes that the movement to get rid of the vestige of old Mass has been around as long as the Thanksgiving turkey. “Somebody’s always trying to take shots at it,” he said.

One person in recent memory was almost successful in his plot against the council. In 2011, former state Sen. Brian Joyce called it “an outdated relic of colonial times” and proposed a panel to approve judicial nominees. Speaking to the Brockton Enterprise, the Milton Democrat said the replacement body “could include the attorney general, the chief justice of the state Supreme Court, and the head of the Massachusetts Bar Association, and others.”

At the time, it was reported that Joyce had the support of then-Sen. President Therese Murray, along with influential senators Barry Finegold, Bruce Tarr, Robert Hedlund, James Eldridge, and Steven Baddour. The editorial board of the Boston Globe even opined that the “Governor’s Council must go,” but Joyce’s bill died in the legislature.

Almost eight years later, the Governor’s Council was the least of his problems. In 2017, the senator was indicted on more than 100 counts of racketeering, fraud, extortion, money laundering, and obstruction—much of it related to alleged political bribery. Appearing in federal court that December, Joyce pleaded not guilty to all charges.

One year later, the senator died, reportedly of an “overdose of a medication commonly used to treat insomnia.” Following his death, prosecutors dropped the case against him.

The battle wages on, however, and every few years the Governor’s Council is called out for its unruly behavior, infighting, undemocratic nature, and lack of transparency. This is an election year, so the fight is at the ballot box.

In Part 2, we will consider the ethical issues posed by attorneys on the council who appear before judges they vote on.