Will former chief parole supervisor Angelo Gomez help or hurt the overburdened board? Some say he is “the right man” and dedicated to “support not surveillance.” Others question his priorities.

Massachusetts parole officers, lawmakers, and prison reform advocates are clashing over the state’s newest Parole Board member. Angelo Gomez, Jr. has begun his tenure to unequivocally mixed reviews.

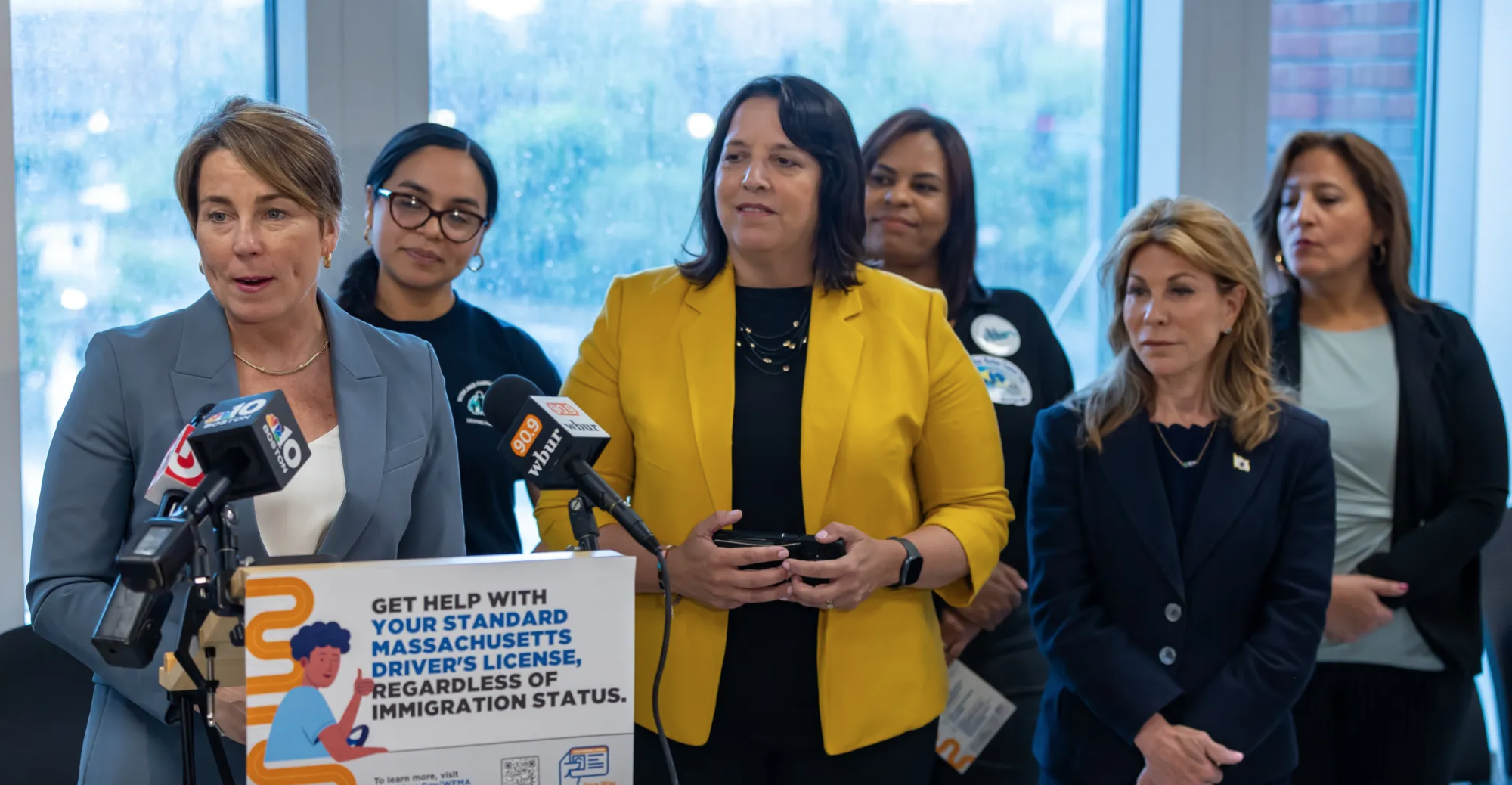

Gov. Maura Healey nominated Gomez, the former chief parole supervisor for the Field Services unit of the agency, on May 28 to fill the board opening left by Tina Hurley. The move came following what was described as a surprising resignation, with some contending that Hurley, who had served as the board chair since November 2022, was pushed out.

Meanwhile, rumors emerged that Gomez was being groomed to take her spot.

The recent record of parole in Massachusetts

Under Hurley, the paroling rate of life-sentenced prisoners had climbed to 65%, the highest in more than 20 years, according to records kept by this reporter and Gordon Haas, a lifer at MCI-Norfolk. The paroling rate for eligible lifers refers to the rate of positive votes for release on parole.

Per Massachusetts law, after at least 15 years behind bars, only those with life sentences who earn parole may serve the remainder of their sentence in the community under supervision by field officers. Before living in the community, parole often requires a year or more of “step down” time for lifers at lower-security facilities.

Rumors spread after Hurley’s departure. Board member Tonomey Coleman, a defense attorney who has served on the body since 2013, was named acting chair by the governor. Attorneys and activists predict that Coleman will soon be a judge, with Gomez then stepping in to be chair.

As the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism reported earlier this year, nine former members have used the Parole Board as a stepping stone to judgeships. Of those who sought and obtained judgeships, seven of them served as chair, while an overlapping seven were former assistant district attorneys.

Why is Gomez controversial?

Gomez was approved by the Governor’s Council (GC) to be a member of the board on June 25. The council is the obscure body that weighs in on a governor’s judicial nominees as well as on picks for the Parole Board and other officials. (We examined the GC in an in-depth three-part series last year.)

Gomez has many supporters, some of whom participated in the appointment process. He was called “an exceptional candidate” by Lt. Gov. Kim Driscoll in the nomination press release. The reputation came from the past three decades of working his way up from corrections officer to probation officer to parole officer to parole supervisor and eventually to chief of Field Services—a third-in-command position under board chair per the agency’s organizational chart.

Field Services is tasked with ensuring those under watch “remain in compliance with the conditions of parole.” Among other duties, officers are responsible for helping supervisees find treatment, housing, and a job, and reintegrate into the community. They also can appear at one’s home or work site at any time, administer drug tests and GPS monitoring, and send someone back to prison for a violation.

In a recent Boston Globe editorial, Sen. Jamie Eldridge, who co-chairs the Massachusetts Criminal Justice Reform Caucus, praised Gomez, saying he was one of “the newer parole officers [who are] much like social workers.” Sen. Eldridge said in an interview for this article that officers like Gomez see their roles as “coaches, not referees.” The notedly progressive senator said Gomez will promote a climate where POs are no longer merely rule enforcers but mentors and motivators.

But Bryan Westerman, a field officer for the past 11 years and president of the Coalition of Public Safety (COPS), the union that represents the Mass Parole Officers’ Association (MPOA), disagrees. Westerman worked under Gomez and calls him “calculating and self-serving.” In a letter to GC members opposing the nomination, he wrote, “I am extremely concerned that if confirmed … Chief Gomez will destroy agency morale, endanger the safety of many, and deter future progress of the agency.”

The letter is posted in full on the MPOA Facebook page and is also accessible here, along with several social media responses echoing Westerman. One of the union leader’s chief complaints is that Gomez “is more interested in politics than public safety. … He gives mixed messages based on his audience and ingratiates [himself to] those in power.”

Westerman added, “The fact that his own colleagues do not support one of our own should be alarming.”

A new council with its old rubber stamp

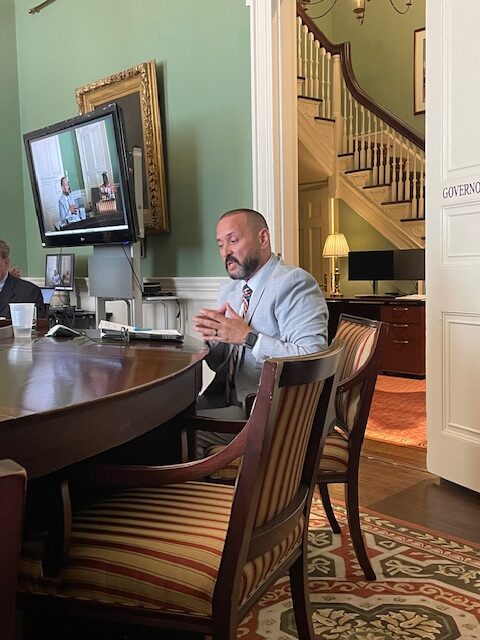

Only one councilor mentioned Westerman’s letter and none highlighted the controversy festering with field officers at Gomez’s hearing on June 18.

In his testimony, Gomez spoke about his family from Puerto Rico, laborers who taught him to be “just in all we do,” and never asking for a “hand-out” but rather a “hand-up.” He also said that he was certain his experience meant he could meet the “challenges” of serving as a board member.

No one asked Gomez to respond to Westerman’s concerns about his “lack of transparency” or his instruction to officers “to violate agency policy.” Nor were there questions about why someone would say he was “universally disrespected and untrustworthy.”

Instead, councilors threw softballs. Councilor Tara Jacobs from Western Mass asked about factors important to Gomez in granting a parole permit. Councilor and former police officer Joseph Ferreira called Gomez an “all-star” and told him, “I love your resumé.” Ferreira’s district extends to Cape Cod and other communities in the southern part of the state.

Overall, councilors grilled the man who came to testify for Gomez—Pamerson Ifill, the Massachusetts Probation Commissioner—more than they grilled the candidate himself. Ifill and Gomez were co-featured in a GBH article when they started their new jobs in 2023, and both described their approach to parole and probation supervision as “less surveillance, more support.”

Ifill said Gomez was “the right person at the right time,” and that he supported new advancements in rehabilitation. Twenty years ago, Field Services hired “wannabe police,” Ifill added, instead of people who wanted to focus on treatment.

Another Parole Board nominee with a law enforcement background

At the Governor’s Council, recently elected member Mara Dolan asked Ifill what he would say to her constituents who disputed another candidate joining the board from a law enforcement background. Dolan is a public defender whose district includes parts of Boston and Cambridge and suburbs from Brookline to Burlington.

Ifill responded that “the noise” around Gomez’s law enforcement background wasn’t nearly as important as Gomez’s belief in “second chances.”

Patricia Garin, a criminal defense attorney who runs the Northeastern Law School Prisoners’ Rights Clinic, testified against Gomez. She pushed back on Ifill, summarizing: “If Mr. Gomez gets on, we have three people who are coming out of probation. Three out of seven is a lot of law enforcement.”

Garin said that the board needs another psychologist to help process the more than 3,000 parole hearings of lifers and non-lifers every year. She also advocated for someone with brain development knowledge and a civil rights attorney, i.e. a larger board for an overworked body, and noted several problems she thought councilors should direct to Gomez, including the unreliability of polygraph tests and the poorly written and out-of-date termination procedures for those on parole.

Councilor and attorney Terrence Kennedy, whose district covers parts of Boston and Cambridge plus nearly 20 other municipalities, told Gomez he was “stunned” that the board uses “junk science.” He said if they wanted to, they “could get rid of [polygraphs] tomorrow.” Gomez said the board “does seem to be heading in that direction.”

A week later, the GC convened its weekly assembly to vote on council matters. Personal Injury attorney Christopher Iannella, whose district includes parts of Boston and the South Shore, was alone in openly opposing Gomez. Iannella, who voted for 96% of former Gov. Charlie Baker’s nominees sent to the GC, stated that he wanted someone with social work or similar experience on the board instead of another pick with a law enforcement background.

In the end, the Gomez nomination was approved in a seven-to-one vote.

Field officers unhappy with Gomez’s leadership

Around the time that Westerman published his letter, parole officer union members voted to determine if they would support Gomez to join the Parole Board. As of July 2025, those eligible to vote were 64 line officers, assistant supervisors, and supervisors, as well as 29 parole officers working in the institutions per the agency’s staff directory.

The poll revealed widespread discontent in the union. The results showed that 43 officers wanted to remain neutral (with no letter sent to the GC), while seven wanted to send a letter supporting Gomez, and 21 wanted a letter of opposition. As a result, no letter was sent.

BINJ spoke with a field officer who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation. The PO spoke openly about his concerns with Gomez, saying he agreed with Westerman’s letter and that Tina Hurley ran the Parole Board well. He commented on the idea that parole officers should be coaches instead of refs—a concept, he said, that was promoted by Gomez under “political pressure.”

He explained, “Angelo doesn’t care about public safety. He cares about whatever it is that whomever is above him wants him to care about—if it will get Angelo what he wants.” He said Gomez was a “puppet” of the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS).

The anonymous PO added that training for new parole officers was lacking under Gomez—only four to five weeks of basics instead of 16 weeks with “a week of criminal law, another week of constitutional law, a week of scenarios—every type of scenario we needed to focus on—CPR, first responders, defensive tactics, how to document and write reports.”

Gomez did not push for training, the anonymous PO said, meaning “he didn’t stick his neck out … not even [for] the free public safety training from the Municipal Police Training Commission (MPTC).” Gomez had done so early in his career, the anonymous PO noted, adding that he had been a “good officer.” He said that some of those MPTC courses included updates on subjects like “cultural differences” and “working with the deaf and blind,” as well as firearms and active shooter training. But the anonymous PO said that Gomez was pressured by EOPSS to ditch the additional training.

We contacted EOPSS for comment. A spokesperson emailed that the “Parole Board remains fully committed to rigorous training that advances its mission of public safety through the structured and supervised reintegration of individuals returning to the community … addressing complex needs such as housing, employment, behavioral health, and family reunification. All parole officers receive a minimum of 40-hours of agency-based, in-service training, aligned with American Correctional Association accreditation standards.”

In our phone conversation, Sen. Eldridge speculated that there is “a tension between the union leadership and the rank and file officers.” The old training, the senator guessed, focused more on surveillance than on support.

In their comments, many responding to Eldridge on his Facebook page appear to be POs who support the anonymous officer’s concerns. One identifying as Mike Jones wrote, “I respect reform. I support second chances. But parole officers aren’t babysitters or therapists—they’re trained to supervise people who are still under sentence. … Pretending like parole is just social work, with no enforcement, isn’t fair to victims, communities, or the people actually trying to do the right thing.”

Support vs. surveillance and concerns about caseloads

Dean Lucier shared similar concerns to those expressed by some of his colleagues online during the field PO’s testimony in April before the legislature’s Joint Committee on Ways and Means. The officer, who is also a doctoral student engaged in these issues, told lawmakers that POs are unable “to conduct safe and effective supervision” because they are now responsible not just for “supervision but also mentoring, case management, crisis response, and—whether acknowledged by policy makers or not—law enforcement duties.”

Workload, the role of officers, and agency priorities are at the center of the debate over the future of parole in Mass. At the Governor’s Council hearing in June, Gomez said he thought the job of a field officer now is “95% social work.” “We’re not police,” Gomez said. “Our mission is different.”

The abovementioned anonymous PO countered that the split should be 75% support and a quarter surveillance.

The average caseload, Lucier told Ways and Means members, is “roughly 39”—but he warned that with Mattis cases coming up for parole, more and more will be demanded of POs. Commonwealth v Mattis was the monumental ruling rendered by the Supreme Judicial Court in January 2024 holding that a sentence of life without parole is now a violation of the state constitution for those under the age of 21 at the time of their crime.

The Mattis decision made approximately 150 people immediately eligible for parole. Our records show that so far, the board has issued 24 Mattis decisions with 21 earning parole. That means most will spend some time in lower-security facilities and then live in the community under supervision.

The anonymous PO also indicated that Gomez may be looking for a pay raise. In 2024, as chief of Field Services, he earned almost $140,000. Tina Hurley earned $169,165 as chair of the Parole Board that year.

“We’re like the Swiss Army knife of the public,” the officer said. The average PO salary is $88,330. He added, “We do it all.”

Navigating the new job

BINJ wanted to see how Gomez approached his new position so we went to two lifer hearings and gathered information (in addition to intel from other hearings we did not attend).

As of this writing, board member Gomez, who is still rumored to become chair, has been on the job for two weeks, presiding with the full Parole Board over 10 lifer hearings. According to our sources who attended three hearings and our own experience, the questions Gomez has asked of parole applicants so far are in his wheelhouse, i.e. about parole plans.

Gomez has inquired about reentry with questions, sources said, such as, “As it relates to being in community, what resources do you need?” And, “In the community, relapse and relationship are the main factors that lead to failure of parole. What is your plan to handle those?”

He also queried about his field of expertise, with concerns such as, “What do you expect your relationship with your PO to be?” And, “Do you consider a parole officer one of your resources?”

One of the most challenging questions he has asked was, “Who in your life will hold you accountable?” And a standard but not easy-to-answer question: “Why should this board believe that you are ready to be supervised in the community?”

At the hearing for Joshua Rodriguez, who stabbed and killed a man in Providence in 2016, the candidate admitted he still had a drug problem behind bars. “I am here asking for help,” Rodriguez told the Parole Board at one point in the hearing.

In her turn, Dr. Charlene Bonner, who Gov. Healey re-nominated to the board in 2023, spoke about the loneliness and depression often leading to addiction and explained how drugs worsened the cycle. Board member Sarah Coughlin, a licensed social worker, asked what helped Rodriguez feel more connected, and less likely to need “to escape” with drugs. He could not answer. When acting chair Coleman asked him what the “prospect” of getting out brought up for him, Rodriguez said, “I want life to be my drugs.”

Board member Gomez took a less direct approach. He did not address the question of “help” for Mr. Rodriguez. He said he did not have the expertise of a social worker like Coughlin or a forensic psych like Bonner. He told Rodriguez that he thought he was “sincere in his remorse,” but “didn’t meet the legal standard for parole.” He then asked, “What does success for you on parole look like?”

Rodriguez, who had no attorney representing him at the hearing, fumbled: “I put my head down and hustle.”

Gomez followed up, “Do you have a plan?” He asked if Rodriguez had access to a tablet to learn more about prospects and opportunities during parole. When it became apparent that he didn’t have one, Gomez suggested that Rodriguez seek out such resources and “build upon his successes.”

As he settles into his new role with critics in the background, Gomez will likely seek a comparable course of action.