An often forgotten chapter in women’s labor history, the fight against marriage bans in Massachusetts eventually found success with activism, passionate union efforts, and nationwide economic change

Helen Leonard was not like other elementary school teachers in Boston.

In the 1940s, the Boston Teachers Union was dominated by middle and high school teachers, and among elementary school teachers, the organization was seen as “the sort of thing nice people stayed away from,” Leonard recalled in a 1981 interview with researcher Kathleen Murphey for her thesis on Boston teachers unions. Elementary school teachers “would usually rather shut up than put up,” Leonard said. “But I wasn’t willing to do that. I joined early. I thought things had to change.”

Leonard did, in fact, change things for women teachers across the state. In 1953, she petitioned to introduce into the Massachusetts legislature “An act providing that female teachers or superintendents of schools shall not be dismissed because of a change in marital status.” Sponsored by Sen. Leslie Cutler, the second woman elected to the state Senate, the measure was signed into law by then-governor Christian Herter on April 10, 1953.

A woman teacher’s marriage, finally, didn’t cost her her job.

The practice of firing married women was common in the US, Britain, and Ireland across professions. In Massachusetts, written and unwritten bans started to pop up after an 1844 act that ruled that school committees could fire teachers “whenever the said committee may think proper.” Boston’s married teacher ban became enshrined in 1883. Once a woman married, she was required to give up her job as a teacher (or clerk, nurse, or flight attendant), and was only sometimes permitted to return as a part-time substitute for less than one third of her previous pay.

Feminist activists, labor organizers, and affected teachers pushed against the policy, but it was difficult to counter what was a popular practice that had supporters in positions of power. The ban was even backed by some groups for women, like the Massachusetts Women’s Political Club, as well as non-union teachers coalitions, like the Boston Teachers Alliance, which not only fought to keep the marriage ban but also actively worked against the union.

The battle against marriage bans in Boston and throughout the state was hard fought and only successful when paired with a unique social and economic time, a postwar era in which the role of women in the workforce was constantly negotiated and changing. The workforce itself was destined for significant change, in part due to the increasingly contested policy. In Massachusetts, at least one third of all teacher turnover was due to women’s resignations over marriage. What was to come was unknown.

The history of marriage bans in the United States

While the fight against marriage bans was a reaction to the damage they did to married women, marriage bans themselves were a reaction. Women’s participation in the workforce was rising through the first half of the 20th century, constituting a threat to the standard vision of women belonging in homes as caretakers. Bans further cemented marriage as a sentence to life in service to the traditional family structure. The rapidly changing economic and social climate meant that practice of the bans was often in flux, rising and falling.

Nationally, the amount of school boards across the country with bans for retaining married teachers crept up from 52% in 1928 to 70% by 1942, according to research by Claudia Goldin, a Nobel prize-winning economist and professor at Harvard University. While that number sank rapidly to just 10% in 1952, Massachusetts in particular held tightly to its marriage bans. In 1926, about 30% of the state’s school committees banned married women for teaching. By 1952, that number had risen to 42%. While there isn’t data for the ’30s or ’40s, Massachusetts stands as an extreme outlier to the national average by 1952, the year before the end of the ban.

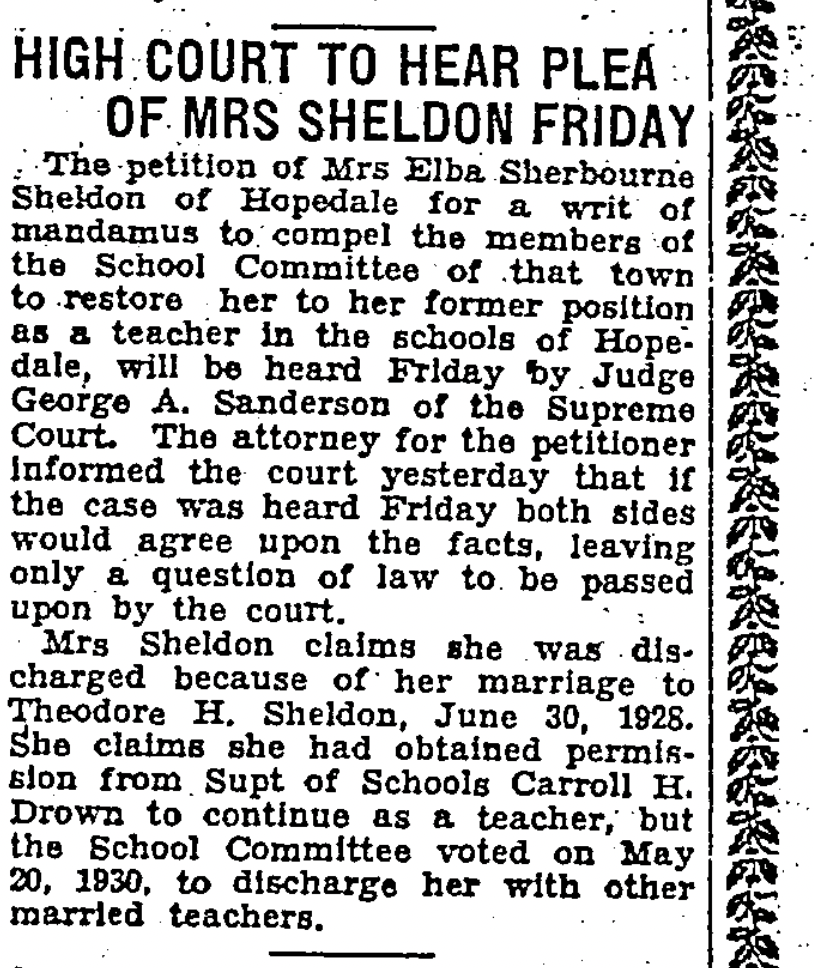

This increase played out incrementally. In the ’20s and ’30s, Massachusetts school boards started to implement more written rules against the marriage of women teachers. The Revere School Committee, for example, instated two rules—one in 1927, and one in 1929—that marriage for a woman teacher “shall operate as an automatic resignation of said teacher,” a rule that even applied to tenured instructors. The next year, the Hopedale School Committee voted unanimously to “eliminate from our teaching force female married teachers.” These two towns brought forth the state’s first Supreme Judicial Court rulings on marriage bans, their discriminatory rules spurring the ban’s first legal challenges in Massachusetts.

Elba Sheldon of Hopedale had been teaching for eight years when the town implemented its new rule. Two years prior, just before she married, she consulted the superintendent and was assured she could stay employed. Still, she was fired. Sheldon petitioned the Supreme Judicial Court to fix the injustice, but lost, the judge ruling that marriage bans were “not so irrational that it is inconsistent in law.”

Five years later in Revere, Clara Rinaldo petitioned for a similar reason, but the judge also decided that she had no case, saying “it is enough to say that … many local school boards in widely scattered parts of this country and in England have taken the same attitude which the respondents here take.” In essence, marriage bans didn’t have to be just or fair. If they were common, they must have been reasonable. These cases became more precedent for any legal challenges to come, further normalizing the bans.

The conservatives who backed the marriage ban in Massachusetts

The marriage ban had powerful defenders in the commonwealth. Conservative men on school committees, city councils, and in courts shut down repeated attempts to overturn bans across the state. Generally, it was near impossible to reverse the bans in court or by petitioning school boards, both of which typically defended the restrictive measures for teachers.

Rhetoric defending marriage bans often took the form of a defense of women. The argument followed that single women deserved teaching positions more than married women, who already had their husband’s income. The women’s groups that defended the bans typically used the second argument, and it was fairly popular as a way of dismissing the claim that the clearly repressive legislation was sexist.

Anywhere marriage bans occurred, advocates argued its supposed defense of single women. In a 1925 ruling against a fired teacher, a senior British judge summarized the argument well: “It is unfair to the large number of young unmarried teachers seeking situations that the positions should be occupied by married women,” he wrote, “who presumably have husbands capable of maintaining them.”

It wasn’t discrimination, ban supporters argued, but a better guarantee of a job for women who lacked support. While many single women advocated the position, it relied on a patriarchal belief that women, themselves included, ought to end up in the home, entirely financially supported by their husbands.

But the argument that bans protected women without support fell flat in practice. In the 1940 case of Houghton v. School Committee of Somerville, the court argued that Fernell Houghton’s claim that she wasn’t supported by her husband wasn’t enough to grant her an exception to the rule against married teachers (and neither was her tenure). If these firings made room for women without financial support, why was Houghton, a woman without financial support (despite her marriage), fired all the same?

Black schools, segregation, and the marriage ban

Arguments centering around “public welfare” were another form of defending marriage bans. A woman needed to fulfill her role in the home for a prosperous society, even at the cost of her individualism.

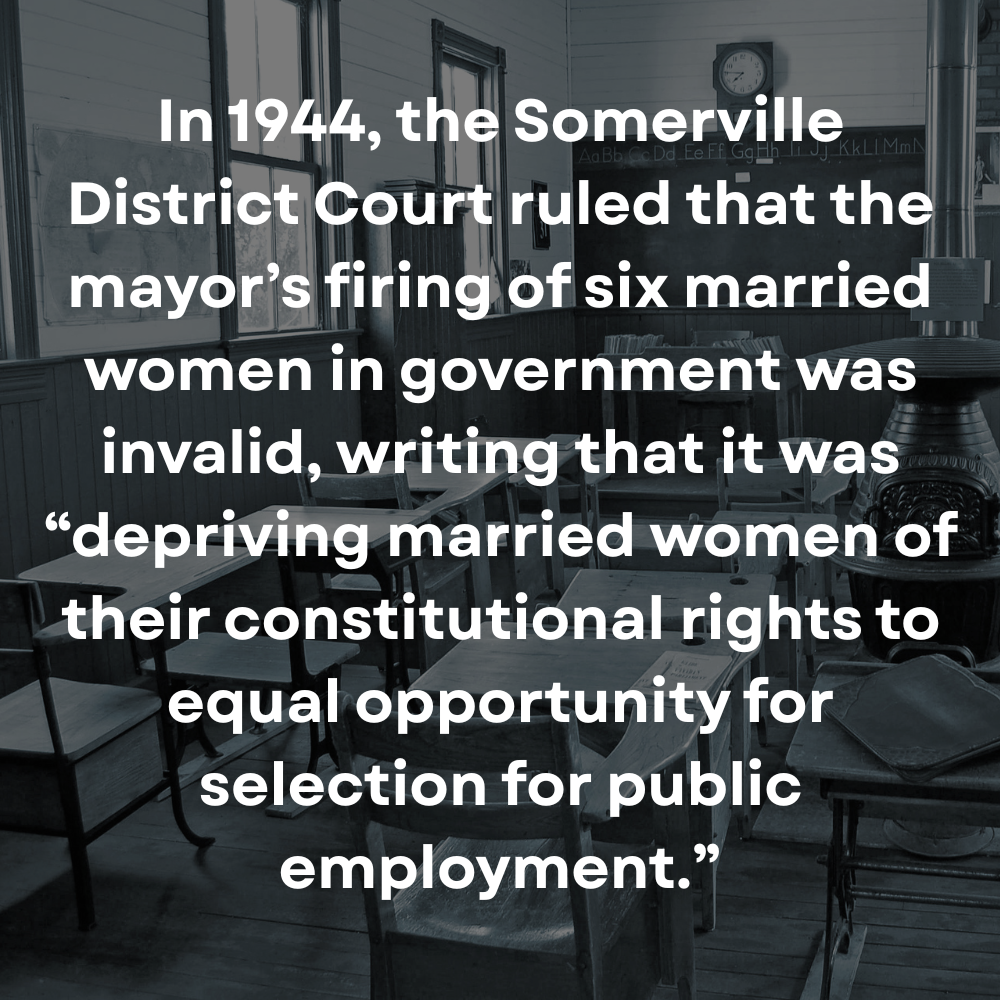

In 1944, the Somerville District Court ruled that the mayor’s firing of six married women in government was invalid, writing that it was “depriving married women of their constitutional rights to equal opportunity for selection for public employment.” This would have marked an impressive leap forward for the city—if it weren’t for teachers being entirely excluded from the court’s new protection. While the court overturned a previous decision to ban married women from employment in the public sector more generally, the precedent of aforementioned cases including Houghton’s, Rinaldo’s, and Sheldon’s, and the Somerville School Committee’s hard rule against married women as teachers was, apparently, too much to ignore. Why? Their firings “might be found to have some rational relation to the public welfare,” the court ruled.

This defense of “public welfare” was revealing of further insidious racist beliefs behind marriage bans. Despite the ban being widely practiced, Black women were largely unaffected, according to Goldin. In going through national census data for areas with bans in effect, she found that there were many married Black women teaching while married white women didn’t seem to keep their jobs. “There weren’t enough Black women to teach,” she said, and due to segregation, Black teachers couldn’t be replaced.

Eileen Boris, professor of feminist studies at the University of California Santa Barbara, noted that while Black women teachers were in shorter supply, school committees also felt there was much less of a reason to fire them. Marriage bans were intended to keep together the traditional family unit. If the Black family unit didn’t matter to those in power, then there was less need to keep them in a strict nuclear ideal.

“Who are the married women you want to stay out of the workforce, nurturing their family?” Boris asked. The exclusion of Black women reveals the intent of keeping white women (and white women only) tied to their family, fulfilling their role within a family unit that put the white male first. But “Black women,” Boris explained, “their family life isn’t important.”

Sabrina Thomas, a librarian and researcher, echoed this in her 2010 thesis, saying that eugenicists treated white married teachers as “suspect” since “they ignored their biological duties to their race and their class.” Women not only had their role in serving men and family, but by extension, serving their race. This traditional framework was deeply ingrained in understanding women’s work.

The marriage ban and the stigma against working mothers

“It was quite a stigma as a married mother to be working. It was quite unusual to stay in the workforce,” Linda Blum, professor of sociology at Northeastern University said.

This popular belief was especially strong during the depression—in a 1936 Fortune magazine poll, only 15% of respondents said that they believed a married woman should work full time. “The combination of economic crisis with social hostility,” Thomas wrote, “added to the economic discrimination placed on married middle-class women.” This could explain the bans’ rise in national occurrence through the ‘30s.

Balancing traditional standards for women and the need for two paychecks also explains the fact that married women could continue to teach part time and for minuscule pay. The “solution” offered by part time work as an option for fired teachers was a big part of marriage bans as they appeared more and more, both in Massachusetts and nationwide.

“Part time work became a touted solution to the work and family balance problem,” Boris said. “Rather than offering childcare, good takeaway food, different hours, that you had during the war, you get the solution of part time work.”

Goldin said that a supply and demand mechanism was the primary mechanism driving the ban across professions. She argued that in the eyes of a school committee, as time goes on, teachers’ pay raises outpace their competency. Marriage served as a convenient point for a cost cutting measure: by firing women before they could spend too much time in the system, schools had an economic incentive to maintain the ban, especially since women were expected to eventually leave to start a family regardless. “One might say this was a dumb thing to do,” Goldin said, as younger teachers are “really quite bad” in comparison to many of the married teachers fired.

Opposition to the marriage ban emerges

Teachers unions emerged as the main opposition to the marriage ban.

At a 1944 hearing, fired teacher Grace Lonergan Lorch, president of the Boston Federation of Teachers (a precursor to the Boston Teachers Union), made her case against the bans. Four of the five Boston School Committee members who heard her arguments scorned her behavior while they and the crowd drowned her out with jeers.

Lonergan Lorch’s strong leadership launched an effort to overturn the ban among teachers who rejected the sexist discrimination and felt that it worsened the existing teachers shortage. The situation was exacerbated by a growing population, threatened cuts to Boston’s teachers college, and the wartime loss of many male teachers.

With advice from its lawyers, the union was “convinced that the case could only be won by organizing public citywide or even statewide pressure,” according to Kathleen Murphey. This led to Lonergan Lorch’s widely publicized 1944 hearing. The immediate push was unsuccessful, but the issue remained a priority for the union. A 1941 Boston School Committee vote to uphold the ban and a 1943 refusal of a petition for the Committee to hold a vote further provoked the union.

The BFT was soon replaced with the surviving Boston Teachers Union, which continued the fight alongside the Massachusetts Federation of Teachers, slowly but successfully lobbying the state legislature on several key union issues. In 1945, MFT Secretary Hugh Nixon successfully petitioned to nearly double the pension allowance for teachers. In 1946, MFT president Frances Masterson, who spoke in support of Lonergan Lorch and against marriage bans at the 1944 hearing, successfully petitioned for a ballot measure to guarantee equal pay between men and women teachers. The referendum passed in 1947, a major victory of a yearslong campaign that had divided the male teachers from the female-led Boston Teachers Union.

The division was so intense that men felt discouraged from joining the BTU. But the union was uncompromising in its equal pay push. Union president Mary Cadigan, who had started the union in 1945 after separating from the BFT, was fierce and sometimes authoritarian, according to Kathleen Murphey, who said that Cadigan was “acknowledged by all who knew her as remarkable, talented, elegant, refined, and also the driving force behind the union.” Her leadership and her supporters were not so kindly viewed by men who opposed equal pay, who said the union was “dominated by selfish and greedy women,” according to letters from a male teacher to the president of the American Federation of Teachers obtained by Murphey.

Strong women, strong leaders

Cadigan’s power brought the union to new levels of strength, something needed in the aftermath of the war with an influx of women in the workforce who believed their work was temporary, hurting women’s identity of working class and union-worthy. “If you didn’t see yourself as a working person because you saw it as temporary, then it’s also difficult to build that identity,” Blum said.

Female leadership in the teaching profession was rare, even rarer was a body of teachers that placed emphasis on equal pay. “Patterns of fine grain segregation” in the power structures among teachers, Blum noted, was persistent, only gradually changing over time (though these patterns remain).

For male dominated unions, “There were limits on what they would do for women.” Blum said, “When we said equal pay for women, we always meant raise them up, but another way to lessen the gap is to bring men down.” This fear was prevented from becoming a reality with a provision in the 1947 equal pay law passed by ballot measure, which detailed that “Such equal pay shall not be effected by reducing the pay of men teachers.”

The movement to overturn the marriage ban

Union pushes were increasingly accompanied by sympathetic lawmakers, and efforts to overturn the ban gained momentum. After state Rep. Louis K. Nathanson told the legislature’s education committee that marriage bans were “outmoded” in 1948, a representative of the Parents Federation of Greater Boston sponsored yet another petition to the Boston School Committee urging the removal of the ban, on the basis that elementary schools were facing a teacher shortage. But yet again, the Boston School Committee voted against the proposition.

Helen Leonard put forward the petition that would undo the marriage ban in 1953, passing 25 to 14 in the Senate on its third time being introduced. In the House, both an attempt to defer the decision to school committees and an attempt to limit the bill to certain towns were rejected.

The ban finally had the opposition it needed on Beacon Hill. The Massachusetts Teacher, a publication of the Massachusetts Teachers Federation, opined that the reform bill “had the good fortune to be argued first in the Senate where three women senators could be of major help; namely, Senators Cutler, Fonseca, and Stanton.” Cutler sponsored the bill, and the latter were two of four new women to join the legislature in 1953.

That year, the union won on several issues, alongside the marriage ban. A slew of new bills passed by the state Senate granted new rights and protections for teachers: school committees could no longer deprive teachers of benefits without a hearing or fire teachers for being too old, teachers over 65 no longer had to pay into the retirement benefits they would receive. The minimum wage was increased and new minimum salary schedules enforced better pay for teachers.

The implications for the teaching profession in Massachusetts were huge. The Boston Public School Superintendent noted in that year’s annual report: “Resignations for marriage in recent years have averaged 50 a year. It will be interesting to observe how an average turnover of 140 to 150 will be affected by this new legislation.”

Despite the new legislation, hiring married women was still banned in some places. While the hiring ban grew and shifted alongside the ban on existing married teachers, ending it was separate and secondary to ending the retain ban. Establishing that married women did, in fact, belong in the classroom was prioritized, and would surely lead to ending the hiring bans. Sure enough, in 1954, the Boston School Committee unanimously voted to end its ban on hiring married women, and other towns and cities followed.

While states across the country had been overturning their own marriage bans, it wasn’t until 1965, with the Civil Rights Act, that marriage bans for any profession were officially over. Nationally, that effect on the workforce was notable—the lifting of bans accounted for over half of new married teachers’ labor force participation, strongly contributing to women’s access to wage labor, according to a 2024 study.

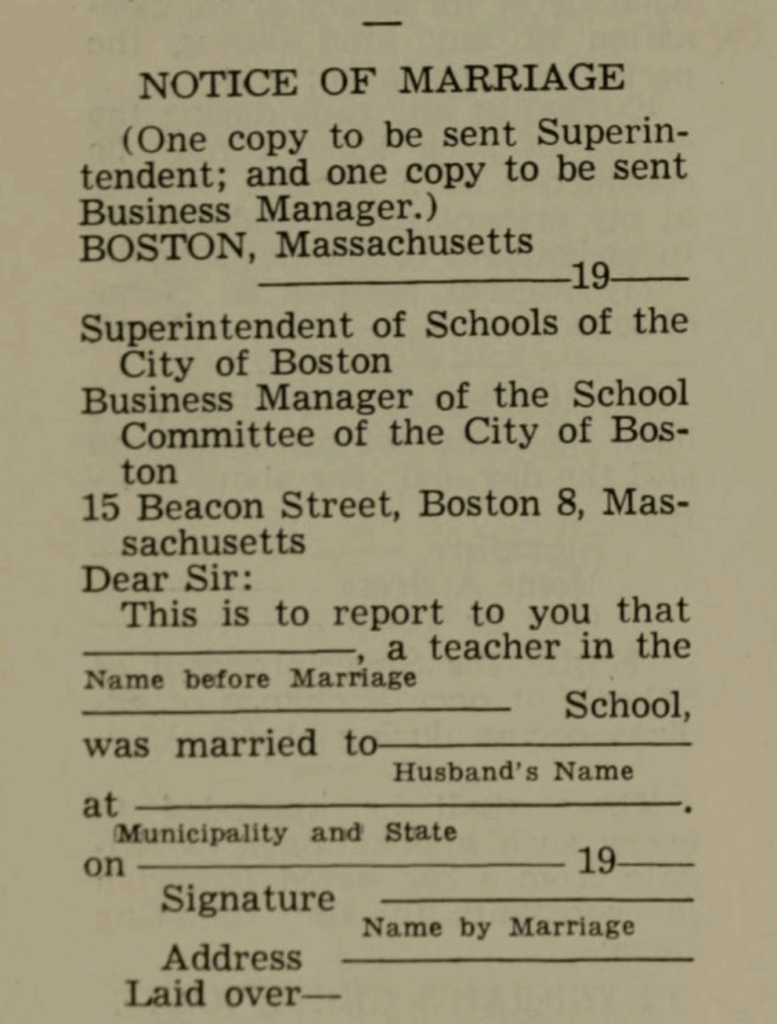

Reports on marriage of women teachers

Responses to the new legislation cropped up quickly. Immediately following the end of the ban, the Boston School Committee voted to enact a new rule that all new married women would have to report their marriages. The new policy, in section 283 of the Committee rules and regulations, followed that if a female teacher were married, “it shall be her duty to report such marriage forthwith” to her superiors. With careful attention, each woman’s maiden name, date of marriage, and new name was published diligently the decades following.

In the mid 1970s, these reports on married teachers were published fewer and further between, as marriages were less carefully tracked. Reports included women who were married months and even years before. It is unclear if the quiet dissolution of the policy was related to the ongoing second wave feminist movement, which emphasized women’s professional development. Originally labelled “Report on Marriage of Women Teachers,” they became “Report[s] of Change of Name” in 1978, separating women into name changes related to and unrelated to marriage. The policy was quietly axed in 1979, with the last recorded name-change report issued that May making no mention of marriage.

The section 283 rule tracking women’s marriages was a direct response to the lifting of the ban. Still, it’s hard to see the reports as purely clerical name change trackers in a time when many teachers would indeed have a new name on paperwork. For example, the language of the reports up until the last year of their existence specifically singled out married women. The form for reporting their name also included their address and husband’s name. This information was unrelated to a name change, but significant as a means of retaining power over these women.

The successors of marriage bans

Marriage bans’ true successor was pregnancy bans, rooted in a similarly socially conservative belief that it would be deeply inappropriate for a child to see their teacher pregnant. In 1954, the year following the prohibition of marriage bans, the Boston School Committee amended the same section with the rule to report and track new married teachers to include a rule that as soon as a superintendent was told that a teacher was pregnant, “he shall forthwith grant her a leave of absence without pay effective at once.”

This leave would extend to at least three months after the expected birth date and could last up to a year and a half, leaving pregnant women teachers without a source of income. Under these circumstances, there was no possibility of even a temporary position during the teacher’s pregnancy.

Pregnancy bans were voted in by the Boston School Committee 4-1. The lone dissenter, Michael Ward, didn’t dissent because of an opposition to the discrimination, but rather because of the idea that it condoned married women in schools. In his statement, representative of the pro-ban attitude up until that point, Ward said that to stop “juvenile delinquency,” mothers could not be allowed to teach. “If they want to visit their children in a reformatory in an automobile which they own because there are two salaries coming in,” he said, they should “give the car up and keep the child at home.”

While marriage bans ended nationally in 1965 with the Civil Rights Act, it wasn’t until 1974 that pregnancy bans were officially lifted by the Supreme Court.

Married and pregnant women’s access to wage labor was a major part of the shift towards a more equitable workforce and more equitable individual lives for women. But with marriage as such a central part of this specific fight for equality, the institution’s inherently misogynistic premise is a complicating factor. “It’s the ideology around the institution of marriage,” Boris said, “that a woman’s loyalties will be divided between work and her family and marriage.”

Boris points out in her 2003 book, “Mothers and Other Workers,” that the right to wage labor isn’t enough and that other social rights are required for the true advancement of women. While straightforwardly a matter of right to wage labor, ending marriage bans is “also a further right that familial status … should not be discriminated against,” Boris said.

Still, inherent inequalities in the wage labor system can shorten broad leaps forward like ending marriage bans. According to Boris, “If you don’t get a living wage because you’re discriminated against on the basis of your gender, then marriage bans are beside the point.”

It is impossible to imagine what the fight to end marriage bans could have looked like in another world, at another political and economic time. As an issue so tied to women’s introduction into the workforce, wartime changes to education and teacher employment, and the depression, the unique circumstances shaped every aspect of marriage bans, especially their resistance.

The teachers unions of Massachusetts of the time were sometimes messy, newly empowered, and in the case of the Boston Federation of Teachers and Boston Teachers Union, made strong by the women who led them.

“I think they were integral,” Boris said of these unions in the fight to end the bans. “They bargain for their workforce, but also for a larger social wage, and if a good portion of your workers are suffering discrimination, you’re gonna be bargaining for them.”