In some cases, our investigation found cities and towns using opioid abatement dollars to fund law enforcement

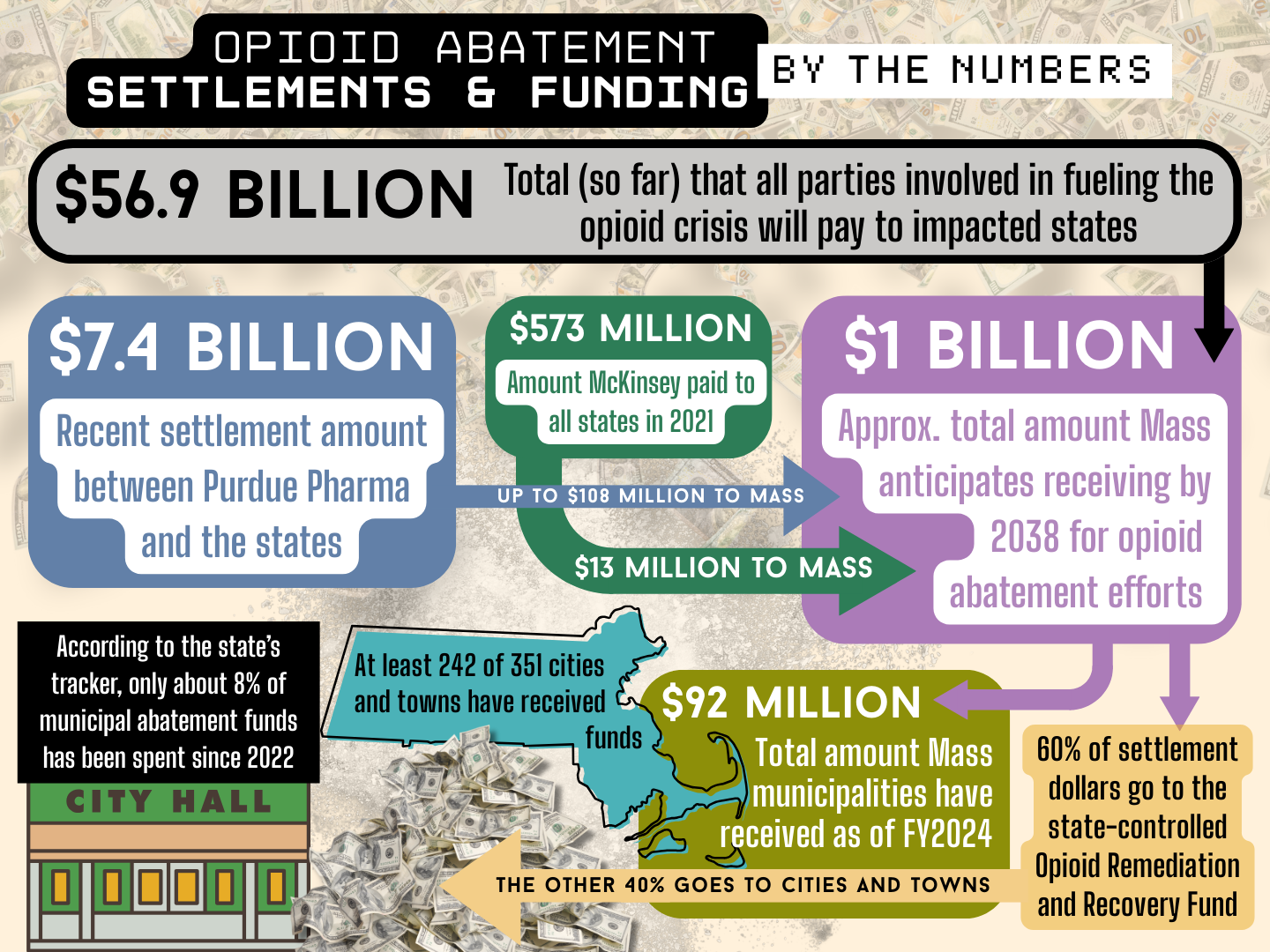

Just months after Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell and attorneys general from other states announced a new $7.4 billion settlement with Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family this January, on March 18, the company filed for Chapter 11 in the US Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York.

The deal will see the Sackler family pay state, local, and tribal governments around $6.5 billion over 15 years. They will also receive $900 million from Purdue—all of the company’s assets—after which it will be dissolved and replaced with a public benefit corporation.

State prosecutors have consistently blamed pharmaceutical companies and associated entities for fueling the opioid epidemic by aggressively marketing painkillers while systematically downplaying their addiction risks. This strategy, many have argued, caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands in the US since the late 1990s. As a consequence, 18 companies including Purdue will pay an estimated $56.9 billion over the next two decades following a series of successful national class action lawsuits.

Money from these settlements began flowing into Massachusetts about two years ago. An early contribution came in 2021 when consulting giant McKinsey & Company paid $573 million nationally (including $13 million to the commonwealth) to settle claims regarding its advice to pharmaceutical companies on maximizing opioid sales.

That same year, the cumulative number of fatal opioid overdose deaths since 1999 surpassed 600,000 in the US. Between 2022 and 2024, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data suggests approximately 300,000 more lives were lost to overdoses, an estimate reflecting the inclusion of provisional data for the most recent period.

Massachusetts anticipates receiving approximately $1 billion by 2038 for opioid abatement efforts, with around $300 million already disbursed. With that funding now arriving, state and local officials have been tasked with mitigating a public health crisis that, according to one study, reduced the nation’s life expectancy by eight months.

The arrival of these funds could mark a turning point in Massachusetts’ fight against the opioid epidemic, provided the money is spent wisely.

Where does opioid abatement funding go in Massachusetts?

The Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism examined how money meant to defray the impact of opioids and prevent further tragedy is allocated across Massachusetts. To date, significant funds have been directed towards administrative costs, and in some municipalities, money meant to address opioid fallout has gone to law enforcement. In most cities and towns, however, the money remains largely untouched.

Settlement funds are divided between local governments and the commonwealth under the State-Subdivision Agreement for Statewide Opioid Settlements. Under this agreement, 60% of abatement funds from settlement agreements go to the Opioid Remediation and Recovery Fund, under the control of the Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS), while cities and towns receive the remaining 40%, which is supposed to be allocated toward recovery efforts. As of last June, the end of fiscal year 2024, at least 242 of the 351 cities and towns in Mass have received funds totaling more than $92 million.

The state fund also receives 60% of any “additional restitution” negotiated in these settlements, with the remaining 40% of that being allocated to the attorney general’s office to “support efforts to enforce compliance with Commonwealth and federal laws and regulations that protect Massachusetts health care consumers or otherwise support initiatives to assist Massachusetts health care consumers and programs.” The state fund receives money awarded from opioid related lawsuits not subject to the subdivision agreement, such as the aforementioned $13 million settlement with McKinsey.

For 2024, the Opioid Remediation and Recovery Fund reported it received more than $200 million. These funds are managed by the state with guidance from a 21-member advisory council. The EOHHS secretary chairs the body, which includes a range of policymakers, public health professionals, legal experts, and clinicians appointed by the governor and attorney general.

How opioid abatement funds are supposed to be used

Abatement funds are intended solely to supplement and strengthen efforts to recover from the opioid epidemic, without supplanting funds that cities and towns would have already spent on substance use disorder treatment programs, and other public health initiatives.

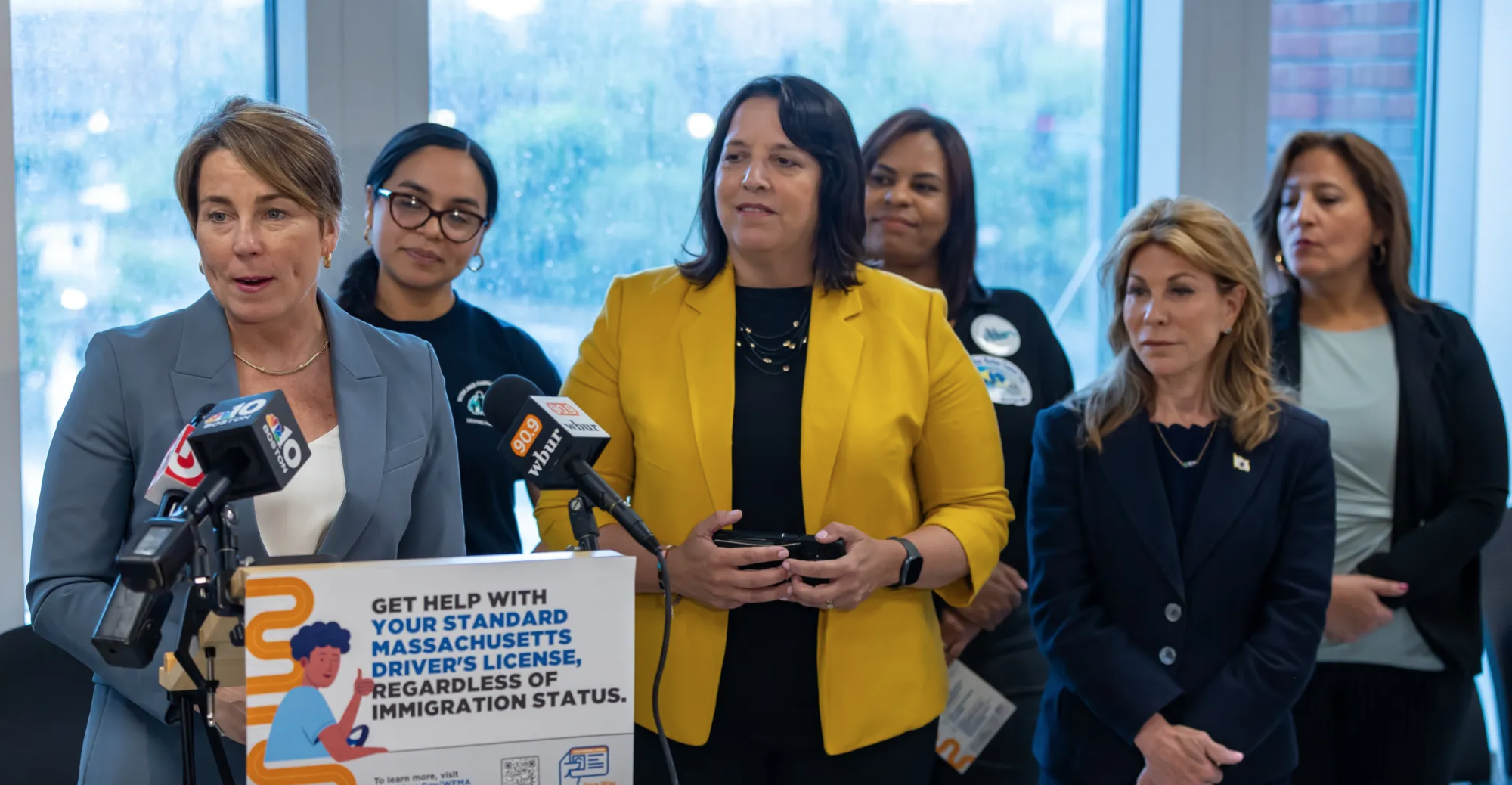

“They’re not grant dollars and they’re not federal funds,” said Erika Hensel, program manager for opioid response at the Massachusetts attorney general’s office. The explanation came during a February webinar hosted by Care Massachusetts, a public-private partnership between the Bureau of Substance and Addiction Services and the global public health and education organization John Snow, Inc.

Municipal workers who are tasked with spending these funds appear to need guidance. To date, few have spent any money at all. According to the state’s tracker, of the $92.1 million that cities and towns have received, only about 8% has been spent since 2022. Last year, the majority of municipalities did not report making any expenditures at all.

“I appreciate future planning. I love putting a budget together for the next however many years, but this is a crisis,” Jenn Robertson, a Care Mass representative, said during the webinar which saw around 100 attendees from local governments across the state.

It’s not clear if the lack of spending has been a strategic decision by local governments, or simply inaction. Policy guidance from RAND has warned against spending settlement money immediately, but few municipalities that did not make expenditures in fiscal year 2024 provided very much explanation for why they did not spend these funds.

The Mass municipalities spending opioid abatement money on administrative costs

For those towns that did report expenditures last year, the largest chunk of money went towards administrative costs, in total more than $1 million of the $4.7 million spent. The following cities and towns allocated 90% or more of their expenditures in fiscal year 2024 to administrative costs: Barnstable ($3,348); Holliston ($30,000); Haverhill ($63,830); New Bedford ($72,957); Springfield ($86,380); Wakefield ($100,000); Westfield ($48,660).

During that same period, Worcester spent 80% of $405,000 on administrative costs. It was the highest amount of abatement funds used by any city last fiscal year—$331,000 was used to pay for the salaries of nine employees.

While cities and towns are allowed to expend settlement money to cover costs associated with planning and operating services, guidance from the Bureau of Substance and Addiction services recommends that they spend no more than 20% of the amount received in a year on strategic planning activities.

We contacted the substance use outreach coordinator for Westfield, a city of 40,000 in the Pioneer Valley with nearly a hundred reported fatal drug-related overdoses in the past decade. They declined to answer specific questions about administrative costs, other than to say the money had been spent on the coordinator’s salary, “community engagement, and harm reduction support.”

Springfield, Haverhill, and New Bedford did not return requests for comment.

The Mass municipalities spending opioid abatement money on police

The state Department of Public Health advises municipalities against “funding law enforcement and/or first responders to engage people who use drugs (PWUD) through post-overdose outreach and/or other engagement efforts.” However, a review of expenditure reports shows that not all local governments are following this guidance.

In 2023 and 2024, the Town of Mansfield, which sits between Gillette Stadium and the Rhode Island border, voted to spend a total of $270,000 of its settlement money to “defray” the expenses of the police department. “We believe that we have used the funds in a way that supplements and does not supplant the funding of the POP [Problem Oriented Policing] Team,” Mansfield Assistant Town Manager Matthew Violette said. “Like many towns, Mansfield is facing difficult budget decisions and the opioid funding ensures we are able to keep our POP Team fully funded and active in the community.”

In Methuen, officials spent $60,000 to hire two patrol officers in 2024, and did not respond to an inquiry seeking additional information.

Spending decisions in Lawrence have also drawn scrutiny. The city reportedly spent about $42,000 to clear homeless encampments. When BINJ requested invoices detailing this expense, the respondent provided a video slideshow highlighting a warming station opened in its library—without addressing the encampment clearing costs.

Lawrence later provided invoices showing that the city paid about $1,700 to have its library auditorium cleaned by a biohazard remediation specialist in February 2023, and about $40,000 for “homeless camp cleanups,” including a $3,000 bill to repair a backhoe which broke down during a cleanup.

Lawrence also entered into a controversial $125,000 contract with Modelo Health, a mobile app company. “I think it was a political favor,” City Council President Jeovanny Rodriguez said in an interview for this article. “Those funds should not be used for the development of [a mobile app] … when we have suffered so much in Lawrence. There’s hundreds of them already developed.”

With or without opioid abatement funds, all hands on deck

In nearby Lowell, the purchase of a cargo van for $60,000 spurred an unnamed public official to alert the attorney general’s office. Documents obtained by BINJ through a public records request show that the van is used by a team of city employees which pick up used syringes in the city. The attorney general’s office is not investigating this expenditure.

“The bigger issue here feels like what is not yet spent much more than what has been spent,” said Hannah Tello, a project director at the Greater Lowell Health Alliance.

“Lowell is sitting on just under $1 million right now,” Tello said. “Sixty-thousand for a van is a drop in our bucket.”

She continued, “I think that the abatement funds were really framed as being this heroic opportunity to solve a major crisis. The reality is that they are helpful, they can be significant, but towns should only be expected to make progress. I think many feel paralyzed with the pressure to choose the perfect, heroic solution.”

According to Tello, the relentless work of dozens of organizations and groups—without any allocated abatement funds—has been instrumental in turning things around in Lowell, which she said in March saw its lowest overdose rate since 2013.

Regarding the bigger picture, the past decade has seen staggeringly high rates of fatal drug overdoses, largely attributable to the introduction of illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, into the black market. Fentanyl is significantly more potent than both prescription opioids and heroin, and its low cost and ease of production make it an attractive choice for drug cartels. In Massachusetts, fentanyl was detected in 90% of overdose deaths in 2023.

There is reason to be cautiously optimistic however. Preliminary data from the first three months of 2024 indicate a continued decline in opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts, following 10% year-over-year declines since 2022. That is despite the presence of a new class of synthetic opioids called nitazenes, which have been detected in counterfeit prescription pills. These substances can be even more potent than fentanyl, and due to their novelty are harder to detect, and can be manufactured with more easily available precursors than fentanyl.

Encouragingly, like other opioids, the effects of nitazenes can be reversed by opioid antagonists such as naloxone—a life-saving intervention that settlement funds are intended to support.