As police and civilian drone usage climbs despite a lack of clear guidelines and changing rules, authorities, advocates, and amateurs struggle to keep a close watch on each other

Although drones are seemingly suddenly everywhere these days, they have been floating above us for more than a century, and actually made their debut shortly after the makeshift Wright Flyer first took off in 1903.

Until recently, modern drones largely remained the domain of top-level researchers and military operators; Massachusetts-based Raytheon in particular continues to develop drone and anti-drone tech for the US government, among others. But over the last decade, their popularity with hobbyists around the world has coincided with use in everything from business and pro sports to espionage. In Boston, it was reported last week that the Massachusetts Department of Transportation is “exploring a future where drones could deliver prescriptions directly to your door.”

Late last year, with political upheaval in the air, people up and down the East Coast reported a number of intriguing if not terrifying drone sightings. To quell the masses, a Trump White House spokesperson later said many of those mysterious flights were approved by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for “research and many other reasons,” but also blamed the phenomenon of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sightings on amateurs. In New Jersey and New York, several airports were affected, while locals from Cape Cod all the way up to New Hampshire also got in on the action.

In mid December, a woman from Harwich, Massachusetts reported “large drones” hovering outside of her house. Before calling the police, she captured video of the crafts, which she shared with NBC10 Boston. Shortly after that incident, two copycats flew into trouble on Long Island in Boston Harbor when they sent a drone into restricted Logan Airport airspace. Boston police arrested two men who now face trespassing charges. During the investigation, local cops worked with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Mass State Police, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the Joint Terrorism Task Force, and Logan’s air traffic control team to locate the culprits.

Although authorities said they were looking for an additional third suspect, an arrest was never announced. With increasingly sophisticated anti-drone detection tools at the disposal of law enforcement agencies from the Berkshires to Boston, and some confusion among users around permissible boundaries, more fines and possibly arrests will likely follow.

A group response to drone proliferation

According to Spokesperson John Boyle, the Boston Police Department has addressed drone issues with other stakeholders for the last two years via the Metro Boston Homeland Security Region (MBHSR) UAS Detection Working Group. Established to manage the growing presence of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) in urban environments, Boyle explained in an email that its focus is “on collaboration among regional partners to enhance detection capabilities, share intelligence, and develop standardized response protocols for drone-related incidents.”

“Over the past year, the group has continued to assess emerging technologies, review federal guidance, and refine best practices to ensure public safety while respecting privacy and airspace regulations,” Boyle wrote. He added that the BPD is unable to provide exact numbers of incidents involving unauthorized drone flights, because they are addressed on a case-by-case basis in coordination with federal partners such as the FAA.

“When drones are found to be operating illegally or posing a potential threat, appropriate action is taken, which can include seizure or investigation into the operator’s intent,” he explained. Local and state police use a variety of tools and methods to detect drones operating in restricted or sensitive areas. These tools are designed to monitor and identify drone activity to ensure compliance with federal and local laws.”

BPD cites security reasons for withholding details about the specific tech and tactics used, but Boyle said the primary focus remains on “detection and risk assessment.” Helping out on that front, as drone use among armchair pilots and photographers has skyrocketed to potentially problematic levels, the free market has stepped in with innovative—or, depending on your perspective, potentially concerning—solutions to help aid police.

Federal grants for drone detection

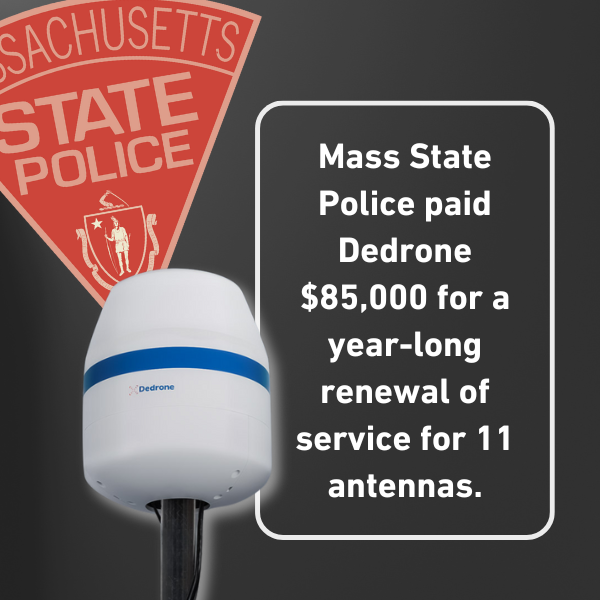

To keep ahead of the civilian drone swarms, authorities in Massachusetts are looking to countries like China and Japan, where drone technology has also exploded. In these places, police have tapped into relatively new tech that uses pirate signals to commandeer rogue drones. Now, counter-drone tech and detection equipment from companies like Dedrone are seeing mass adoption in the US, and not only in critical areas like near airports.

In 2024, according to the Mass Office of Grants and Research, state police paid Dedrone, which was acquired by Taser and body camera maker Axon last year, $85,000 for a year-long renewal of service for 11 antennas. Per the DHS grant program’s state share application, the funding was approved last October and runs through June 2026. Grant funding for a similar program was secured by MSP in 2023 to the tune of $60,000.

According to the application filed by the state police director of billing and grants, the system they acquired can detect a drone’s position and the location of the operator, as well as the spot where the drone was initially launched from.

“This grant will continue to provide the MSP and our partners with detecting drone operations in and around restricted airspace as well as areas of high security concern such as airports, stadiums, prisons and large open-air venues,” the MSP director said. Think the Boston Marathon, July 4th celebrations, MLB games, and concerts at Fenway Park.

Drone detection vs. drone mitigation

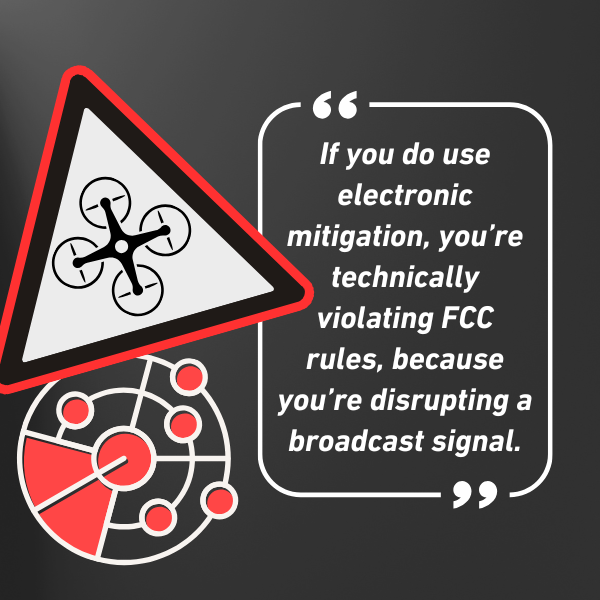

Although he wears many hats as a drone pilot, photographer, and videographer by trade, Vic Moss is also the CEO of the Drone Service Providers Alliance, an organization of 33,000 members who are drone pilots across the country. As a consultant, he has worked with agencies like the FAA to advise on regulatory measures concerning UAVs, and said counter-drone technology falls into two different categories—detection, and mitigation.

Detection is legal, Moss said, and can be done with almost any phone using remote ID apps. “I could literally find somebody flying a drone and where they’re standing,” he said. “Cops can do that. They have the Dedrone, they have AeroScope, and a bunch of different types of things where you can detect equipment.”

Mitigation, on the other hand, is trickier. Currently, Moss said, only federal agencies are allowed to use mitigation efforts—that includes the Department of Energy, Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security, Secret Service, and the Department of Justice. But that could change soon. Moss said a federal pilot program to offer counter-drone training to local and state-level agencies is in the works. For now, though, law enforcement is mostly playing catch up.

“The biggest issue with this type of stuff is training and identification,” Moss said. “I know people who do mapping—people who might map a residential street—they’re going to be flying back and forth. And so somebody calls the cops, cops show up, use their little remote ID app, find out where, and it’s up to them to find out if it’s a threat. Then what do you do? How do you mitigate?”

Moss explained the options: “You can do it electronically. You can do it kinetically. Another way to mitigate this is to find the operator and ask them to land. But if you do use electronic mitigation, you’re technically violating FCC rules, because you’re disrupting a broadcast signal.”

Moss said he believes that local and state agencies, under the right circumstances, should have the permissions and ability to mitigate, but not kinetically. There’s simply too much that can go wrong with just “shooting down” a drone—from fires set off by lithium polymer batteries, or drones landing in crowds.

“Clueless people, careless people, and criminal people. The laws and the regulations and the mitigation training, that kind of stuff is really kind of geared towards the clueless and careless, and education as well,” Moss said. “Mitigation itself is going to be a very, very tough, slow road. We have to be very careful with it to make sure it’s done right. It needs to happen.”

Ultimately, Moss said he’d like to see federal agencies be more proactive in their approach to training, public outreach and transparency, and coordination with state regulators. Speaking about the mass hysteria and sightings up and down the eastern seaboard last year, he said, “There were definitely drones in the air”—some of them he was personally familiar with. But “the vast majority of those,” Moss said, “were aircraft.”

Monitoring police drone use

While authorities are occupied with monitoring drone use by civilians and potential evildoers, civil liberties advocates have long been concerned with the unrestricted use of drones by cops and other agencies—local, state, and federal alike.

In the commonwealth, the ACLU of Massachusetts has spent years plumbing for all relevant records, and reports that “according to late 2023 data, it remains the case that almost half (43%) of active government drones in Massachusetts are registered to police departments.” The numbers are skyrocketing.

“The total number of drones registered by government agencies increased by 169 between 2021 and 2023,” according to an ACLU drone tracker. “The Massachusetts State Police acquired 19 additional drones, amounting to a 25% increase in the department’s drone fleet. Likewise, the Norfolk County Sheriff’s Department, which had a single drone in 2021, had acquired 19 more drones by 2023.”

In Boston, as BINJ reported in January, a self-described “leader in drone technology and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) solutions” announced that it secured FAA permission for “drone operations over people and moving vehicles.” The introduction of third-party contractors to the equation only further muddies matters. As Alex Marthews, the national chair of Restore the Fourth, an organization that “stands against mass government surveillance,” explained, there’s no law dictating what law enforcement can or cannot do with UAVs (for example, there are no rules that “prevent them from being armed or equipped with flamethrowers.”)

Even Cambridge, which has an ACLU-backed ordinance requiring community control over police surveillance, may soon have police drones overhead. Police there presented the request for them as urgent, and Fourth Amendment advocates and community members are still waiting on a draft policy and subsequent city council vote. Whether in Cambridge, where the acquisition of UAVs seems inevitable, or in a jurisdiction where they are already in the sky, the specifics of these policies are critical.

“For a long time, we have believed that law enforcement should obtain a warrant before using drones,” Marthews said. “In other words, law enforcement can and should use them for surveillance, but only when investigating an actual crime, not for the general purpose of keeping an eye on things. … As drones become cheaper to operate, and drone footage becomes cheaper to store and analyze, the risks grow of them being used as general-purpose mass surveillance tools.”

The ACLU, which pushes back on cop drone use for safety reasons citing crash reports as well as for privacy issues, has a similar position: “While Massachusetts has no laws on the books regulating police use of drones, the ACLU of Massachusetts supports legislation that would ban the weaponization of drones and other robots.”

New drone policies and Remote ID

In addition to offering stationary and mobile mitigation tech like their DroneDefender jammer and accompanying tracker software, Dedrone sells its monitoring services to cities like Boston to implement around places like Logan Airport through an app called DedroneCity. Notably, the company also offers vehicle-mounted drone protection and tactical options like complete Counter Unmanned Aerial Systems (C-UAS), as well as drones as first responders.

This stuff comes in handy for local or regional authorities looking to watch drones, because for the most part, the FAA doesn’t exactly know who’s flying what or where. A technology called Remote ID, which is slowly rolling out, will eventually change that; the trackers can be built in or purchased separately and added as a module. Still, the millions of amateur drones out there are hard to track. According to the FAA, there are more than a million registered drones in the US—approximately 412,000 commercial registrations and 384,000 recreational flyers—up from fewer than 800,000 in October 2024.

Part of that registration boom comes from two FAA directives on drone identification in the last two years. In September 2023, the agency issued a policy saying it would exercise discretion in determining whether to discipline drone operators who failed to comply with the Remote ID rule, but that policy ended last March.

The current rules call for drones that are used for recreation, business, or public safety—as well as those which are foreign registered—to be equipped with Remote ID. The technology acts as a digital license plate for your UAV, broadcasting information like location, altitude, and your registration number to nearby authorities and airspace users. The federal call for compliance, however, has grown much more complicated for civilian users this year, since the world’s largest drone manufacturer, DJI, put the onus on operators to avoid restricted airspace, like the area near Logan Airport. On Jan. 13, the company updated its geofencing system, effectively removing the automatic restriction feature.

Boyle, the BPD spokesperson, said that geofencing has traditionally served as a built-in safeguard to prevent drone flights near government buildings and other protected areas. He added that removal of these barriers increases the importance of user responsibility and compliance with regulations. “We continue to monitor these developments closely and work with our regional and federal partners to ensure any risks are mitigated,” Boyle wrote.

In an attempt to rein in public drone use and clarify the dos and don’ts for private operators plus municipalities and law enforcement officials trying to monitor them, Massachusetts lawmakers have proposed an Act relative to unmanned aerial systems. In addition to setting a fine of $100 for violations of FAA drone regulations, the comprehensive measure prohibits drone surveillance and also notes: “no person shall equip or operate a UAS or UAV armed with a weapon capable of causing serious bodily injury or death.”

Meanwhile, regarding the policing of police drones, there are bills proposed in the Mass House and Senate that would place restrictions on the use of unmanned aerial systems for state surveillance. Comparable measures have failed on Beacon Hill several times before.