How Massachusetts State Police are using the opioid crisis to pursue “profound and dangerous erosions of privacy and civil liberties”

Imagine tailgaters partying in the parking lot of Gillette Stadium.

A large Silverado slowly rolls past the revelers. On the outside, it looks like every other pickup at the game, minus the Patriots bumper stickers. But behind the tinted windows and under the hardcover cargo shell covering the bed is a cluster of antennas and blinking lights.

The truck belongs to the Massachusetts State Police, and it’s carrying a so-called cell-site simulator—a sophisticated surveillance unit used to gather mobile phone data and locate users. Police say they are trying to track one person, but in practice they are actually accessing every phone in the lot, and possibly into the stadium itself.

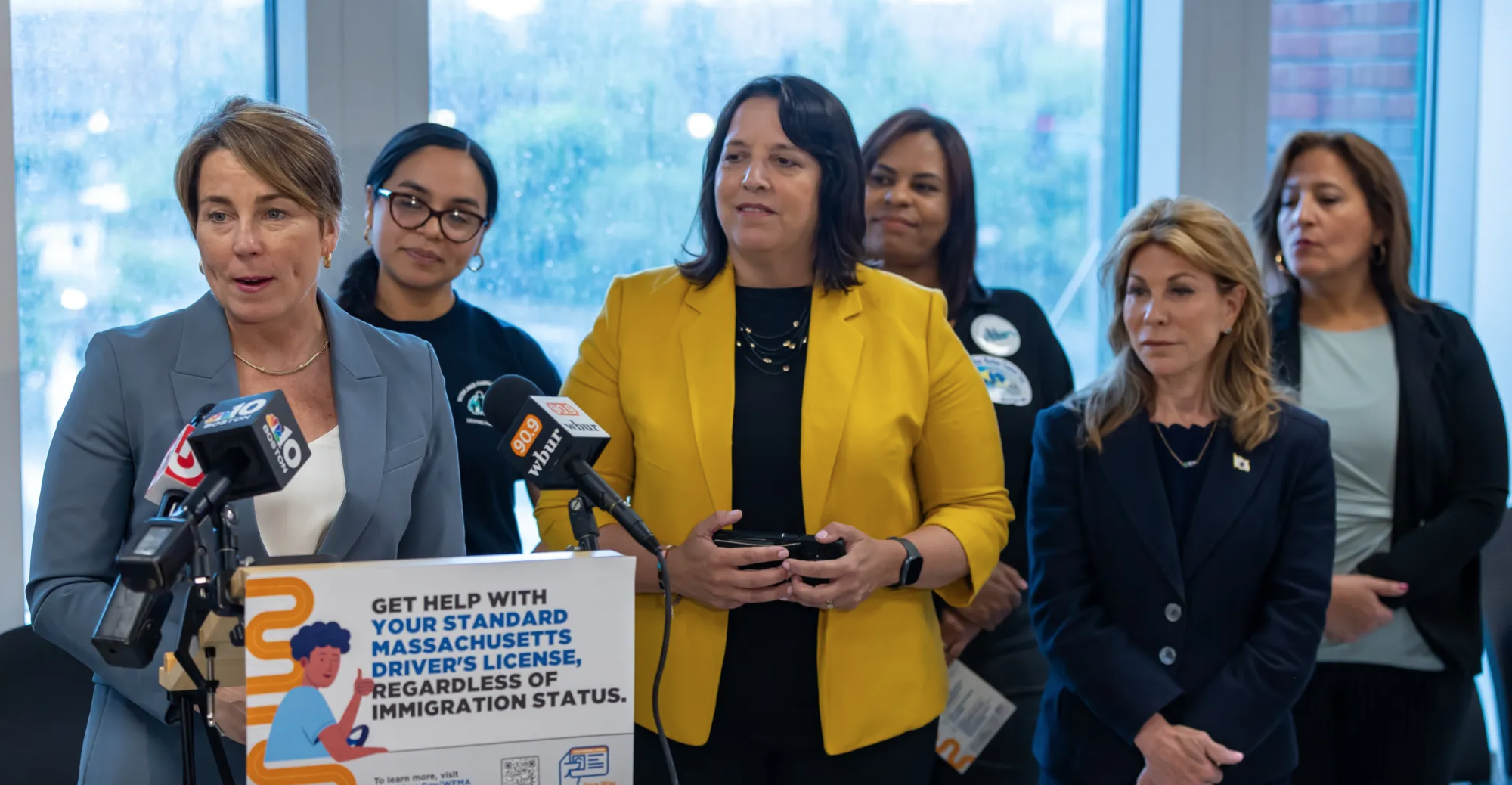

The above scenario could soon become reality throughout Massachusetts later this year, as state police look to purchase a new cell-site simulator (along with a Chevy heavy enough for the spy equipment) that can be used across the commonwealth, tracking tens of thousands—if not millions—of personal devices. The systems would be run by the same department that is currently rocked by a bribery scheme, in which troopers allegedly accepted snow blowers and bottled water as bribes in exchange for helping unsafe drivers secure commercial truck-driving licenses.

As the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism has shown in prior reporting, there is no substantial oversight of MSP procurement. In this latest example of the apparent opacity, civil liberties advocates said the department is downplaying the way simulators can invade cell phones and retain information. They fear the new tech could lead to suppression of free speech and questionable criminal cases, where prosecutors won’t reveal where they acquired information used to target suspects.

And while the police say they will use simulators to track fugitives and find kidnapped children, the million-dollar system is being paid for by a federal anti-heroin grant—which suggests the focus will be on drug cases, advocates said.

“The people in Massachusetts and the US really need to be aware of the degree to which the completely failed war on drugs is leading to profound and dangerous erosion of privacy and civil liberties,” said Kade Crockford, Director of the Technology for Liberty Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts. “They are impacted by the militarization of police and departments getting military-style technology to wage a failed war they’ll never win.”

The Committee for Public Counsel Services has sued the state police for failing to turn over information about surveillance, and CPCS Forensic Services Director Ira Gant said use of a cell-site simulator could lead to citizens’ rights being violated.

“Capturing a person’s cell-phone signal and tracking them in real-time, as the State Police aim to do with truck-mounted and handheld cell-site simulators, require a warrant supported by probable cause. To do otherwise violates the most basic of our constitutional rights,” Gant said. “The federal and state courts have routinely held that people have the right—absent proof they have committed a crime—to be free from police intrusion, including their devices.”

State police did not respond to questions about what kind of oversight the cell simulator program would have, how it plans to use the program, or how police would retain data collected through the simulator.

Fooling phones

According to a request for response released last month, the state police are specifically shopping for a cell-site simulator—commonly known as a “Stingray,” after the brand name of one popular product option—with a potential price tag of $1 million. The department wants to use the device for at least three, and possibly eight years.

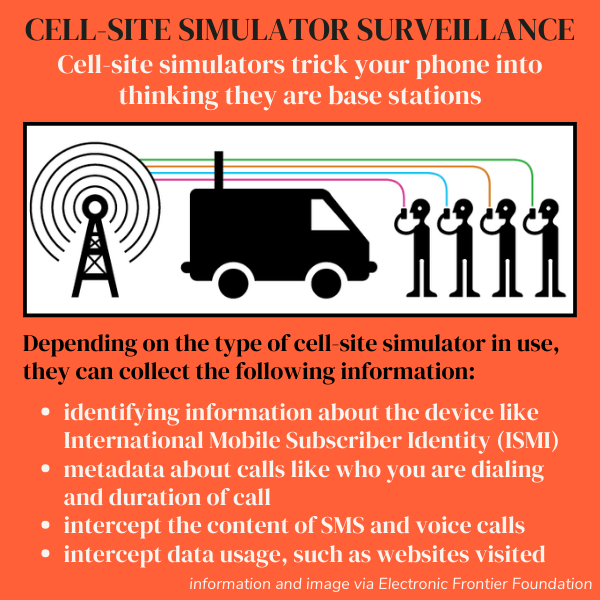

As a person carrying a cell phone moves from place to place, their device connects with the closest tower in range, which is putting out its own signal to maintain service. Cell-site simulators work by broadcasting stronger signals, fooling phones into disengaging from towers and connecting with the imposter instead.

Once they are connected, police can then collect the International Mobile Subscriber Identifiers—the numbers unique to each phone’s SIM card—and use triangulation and antennas to determine direction and distance to locate individual phones, according to Cooper Quintin, senior public interest technologist at the tech watchdog Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Just by turning on cell-site simulators, police can cause harm, Quintin said. Washington Sen. Ron Wyden confirmed that when the simulators connect with phones, they can interrupt 911 calls instead of passing them through to emergency responders. Wyden has even pushed for federal regulations of cell-site simulators.

Quintin said police may get phone information for a specific suspect through the phone company and then use a simulator to track them. Authorities often use “exigent circumstances” like kidnapping or an escaped fugitive to justify tracking. But a simulator grabs every phone in its radius, and as most simulators are mobile, that means it can pick up IMSIs from everywhere it travels.

According to experts, cell-site simulators have a working range of about 1,600 feet—and because they’re mobile, that range extends as they move. A simulator at a Pats game could potentially scoop up the IMSIs of everyone there.

“Looking at a map of the stadium, it would depend where in the parking lot police were and where in the stadium somebody was,” Quintin said, “but it would be accurate to say some people at the game itself would get captured by the [simulator], and if the police went on a tour of all the parking lots, probably everyone would get caught.”

Having those IMSIs gathered at that time and place means police can triangulate that location information as well. And if police retain that data, they could use it against people in future cases.

“We already know the Massachusetts [Supreme Judicial Court] is very concerned about police using information they’ve acquired through one investigation against someone in a separate investigation,” Crockford said, referring to a ruling related to body camera footage being used to prosecute an unrelated case. “Obviously the danger is [that] police could bust this technology out once a week to find someone in circumstances they believe to be exigent, and sweep up hundreds of thousands or millions of cell phone records in a dense area like Boston, and then retain that information and use it however they choose to.”

Law enforcement agencies have used Stingrays for years, and while civil rights advocates and legislators have pushed back on the practice, they’ve had limited results. A 2023 bill that would have prohibited cell-site simulator use in Rhode Island without a court order died in committee.

Meanwhile, the federal Office of the Inspector General found that Secret Service and ICE used Stingray tech without a court order.

Cell-site simulators aren’t only hidden from view of the public they’re surveilling, but from potential political and legal oversight. In 2021, WBUR reported how the Boston Police Department secretly purchased their own simulator—without approval from the City Council—using civil forfeiture funds.

As for MSP oversight, BINJ has reported about the department (in conjunction with other state law enforcement agencies) spending millions over budget on everything from practice ammo and handguns, to tasers, chemical munitions, and ballistic blankets. There is no internal board, state entity, hired outside apparatus, or effective legislative mechanism in place to block any state police purchases.

Collecting and obfuscating

The state police request is clear about the desire for mobility—and secrecy. It calls not only for a simulator, but a Chevrolet Silverado 2500 to carry it, complete with a cargo bed “preferably with antenna elements installed under [a] false ceiling so as not to be visible from the outside.”

And the request also contains language that advocates said seemed to downplay the scope of a simulator’s capabilities, protesting too much about its alleged lack of intrusion.

“Cell-site simulators do not function as a GPS locator, as they do not obtain or download any location information from the device or its applications,” the request reads (emphases included in the bid solicitation). “Cell-site simulators do not collect the contents of any communication, nor does it capture any data contained on the device such as emails, texts, contact information or images and does not capture or provide subscriber account information such as names, addresses or telephone numbers.”

But downloading is irrelevant, Quintin said—police can still track the locations of thousands of people with the technology.

“It’s a classic use of weasel words … It’s dodging the question of how and what it’s actually used for—to track a specific person, and to potentially use it to gather the IMSIs of everyone in a specific area, then send them to the phone company and get names,” Quintin said. “You can use it at a gun shop to see who’s buying guns, at an abortion clinic to see who’s getting abortions, at a protest to see who’s protesting. That’s where there are pretty significant concerns.”

“The language is obfuscatory,” agreed Alex Marthews, founder of the privacy advocacy group Digital Fourth. “Even if the police technology doesn’t download information, it will still be obvious that every phone that was collected was near a simulator at that time. I think police will likely get to at least see the list of numbers pinging off the tower. Usually, they may then retain and exploit that information for other law enforcement purposes.”

And Gant said the request’s language ignored how some simulators have far-reaching capabilities.

“I am concerned that the State Police are downplaying the abilities of these devices. Many cell-site simulators can be used to obtain and store the data or contents of a phone, which can include call history and text messages,” Gant said. “These devices can also be used to sweep up and identify every operating cell phone in the cell-site simulator’s area—even those who are not the target of police activity.”

And the mobility of these units makes it easy to use this tech to easily collect info about people at mass events. Marthews said that even if police apply for a warrant to locate a particular IMSI, the collection process will still pull in phones belonging to people outside of the warrant’s scope.

“The warrant can be authorized for a particular person, but a cell-site simulator collects all devices in its radius—that collection is not particularized, there’s no probable cause to suspect everyone else. This has implications for surveillance of mass events in general, like protest activities.”

Marthews continued, “For example, police would be hugely interested in having all of the phone numbers of people attending a protest against police brutality. They could hold onto those numbers and exploit the communications links they disclose without bringing prosecutions against those involved. Data is leverage.”

Pulled prosecutions and parallel constructions

Police will often not specify they’re using a cell-site simulator when applying for warrants for surveillance. Crockford of the ACLU said that often keeps their use from being scrutinized. But in Mass, the Supreme Judicial Court has ruled that police needed to obtain a warrant before demanding a cell provider locate a phone in real time, and in a footnote said alternate uses of surveillance technology would also require warrants.

“It doesn’t take a legal genius to see that … if you want to hijack someone’s cell phone and use a device to track their location, you need a warrant for that. That’s not exactly a fringe idea,” Crockford said. “It was always obvious courts would end up concluding the use of Stingray requires a warrant. I think law enforcement knows that this is the case, and that’s why it’s shrouded in intense and troubling secrecy.”

Crockford added that the ACLU filed a public records request about BPD’s Stingray use. From the resulting documents, privacy advocates learned that even though department policy required cops to get a warrant before using the device, they never did. Instead, they invoked emergency or exigent circumstances instead every time.

As a result of its frequent clandestine deployment, people charged with crimes based on evidence gathered via cell-site simulators often have no idea the technology has been used against them.

“Not only is the public at the mercy of police departments and whether they want to disclose the truth, so are criminal defendants,” Crockford said, explaining how police can use “parallel construction,” creating a fake chain of evidence to obscure how they obtained information leading to charges. “Defense attorneys can’t object to surveillance that they don’t know happens, that’s the purpose that secrecy serves when it comes to tech like this.”

The use of false info by cops helps keep mentions of cell-site simulators out of the courts, and that is just how cell-site simulator manufacturers and law enforcement officials like things to be. The FBI has told prosecutors to drop cases if it looks like a defense attorney might force disclosure of how a Stingray was used in the investigation.

“Manufacturers do not want a situation where the use of a cell-site simulator is challenged in court and then is excluded because it led to non-particularized over-seizing of innocent people’s data,” Marthews said. “That would be very damaging to the business model.”

Crockford said, “If the court had the opportunity to evaluate Stingray use, they could have the opportunity to rule on the constitutionality of that surveillance, and for years police have wanted to avoid being forced to use a warrant for this surveillance.”

Drug money

In the request, state police emphasize the exigent circumstances aspect of Stingray use.

The solicitation reads: “Cell-site simulator technology provides valuable assistance in support of important public safety objectives. Whether deployed as part of a fugitive apprehension effort, or an exigent circumstance to locate or rescue a kidnapped child, cell-site simulators fulfill a critical operational need.”

Further down, the request notes the simulator is being procured “to support activities associated with 2023 COPS AntiHeroin Grant award received by the MSP.” And the federal government’s description of how that grant money should be used is clear, saying it is “designed to advance public safety by providing funds directly to state law enforcement agencies in states with high per capita rates of primary treatment admissions for the purpose of locating or investigating illicit activities through statewide collaboration relating to the distribution of heroin, fentanyl, or carfentanil, or to the unlawful distribution of prescription opioids.”

The grant funding does not focus on treatment for those admissions, though. A Department of Justice FAQ makes spending under the grant even more explicit, saying it can be used for “Equipment directly related to anti-heroin and other opioids investigation activities,” and “overtime for sworn officers and civilians engaging in anti-heroin and other opioids investigation activities.” And while the DOJ encourages “collaboration with agencies involved with treatment [and] prevention,” these funds cannot be used for prevention itself: “Agencies may only request funding for costs directly related to anti-heroin and other opioids investigative activities.”

Crockford said the ACLU’s investigation of the BPD’s cell-site simulator program found it was almost exclusively focused on drug cases. The organization criticized spending on Stingrays instead of treatment programs.

“You still see a tremendous amount of money and resources being poured into fighting back against an illegal drug market,” Crockford said. “It’s a failed enterprise. It’s not only led to more death and more despair, but people need treatment.”

Crockford said there needs to be strong oversight of any cell-site simulator used by state police. While communities like Boston have ordinances that require law enforcement to disclose what surveillance equipment they’re deploying and what they plan to acquire, there are no similar laws at the state level.

“It’s more of a challenge because it’s unlikely the legislature wants that responsibility. It is a real problem, and one that collectively we need to figure out how to address.”

Crockford noted that the legal system can provide some limitations: “Courts have the opportunity to and ought to limit police in the warrants they authorize, limit what police can do with the information they get from people that are not targeted. There ought to be language that orders police to immediately delete information not pertinent to the phone they’re targeting. That doesn’t happen if police say they’re using Stingray in exigent circumstances.”

There is one important restriction in the state police request. Because the funding is coming from the federal government, the department agrees to not “enter into any contract to procure or obtain any covered telecommunication and video surveillance services or equipment produced or provided by … an entity that the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of the National Intelligence or the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, reasonably believes to be an entity owned or controlled by, or otherwise connected to, the government of China.”

For the record, the Chinese government isn’t allowed to spy on people in Massachusetts. That’s the job of state police.