What the Mattis decision means for parole in Massachusetts—unprecedented opportunities for release from life sentences, updated trainings for attorneys, and a big shift in the system

Since the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) announced its landmark ruling on Jan. 11, many with a sentence of life without parole (LWOP) have been given “new hope,” said Shawn Fisher, a prisoner at Old Colony Correctional Center. Protections against mandatory LWOP, which was declared unconstitutional for juveniles in 2013, will now be extended to emerging adults, meaning those who were 18 to 20 years of age at the time of the crime.

The watershed ruling, Commonwealth v. Mattis, a 4-3 decision, is based on the case of Sheldon Mattis. In 2011, as an 18-year-old, Mattis gave a gun to Nyasani Watt, and was later found guilty of encouraging Watt to shoot two boys who were allegedly members of a rival gang. One was killed, another wounded. Watt and Mattis were each convicted of murder, but the former, a juvenile, was deemed eligible for parole after 15 years. Mattis, now considered an emerging adult, was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

Fisher, a second-degree lifer who earned a positive parole vote last year, was overjoyed for the 208 men and women behind bars in Massachusetts, many who have served 20, 30, and 40 years in prison, and who will now be eligible for parole since the ruling is retroactive. That number of eligible prisoners was confirmed for this article by Mara Voukydis, director of the Parole Advocacy Unit at the Committee for Public Counsel Services. The CPCS is the state agency that oversees legal assistance for indigent defendants.

Parole eligibility gives people an opportunity to serve the remainder of their sentence in the community, but is no guarantee of release. Like Fisher, most who earn parole must complete six to 12 months in a lower-security facility, then go to transitional housing. Parole supervision, as we reported in a prior article, is always difficult, and can be like “dancing on banana peels” for those who are still in the state’s clutches.

Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly emphasized the significance of Mattis, in which “the SJC became the first state supreme court in the country to decide that sentencing an ‘emerging adult’ … is every bit a violation of the state constitution as when such a sentence is imposed on a juvenile.” And the Sentencing Project explained, “While two other states, Washington and Michigan, have judicially barred mandatory life without parole sentences for late adolescents, this decision marks the first state in the nation to categorically bar life without parole sentences—whether mandatory or discretionary—for this population.”

But while many of the 208 impacted people want to start the hearing process as soon as possible, more criminal defense attorneys need to be trained in light of the new SJC ruling in order to properly prepare their clients for proceedings.

“A fair number of these emerging adults have been behind bars for decades,” said Patty Garin, co-director of the Northeastern University School of Law’s Prisoners’ Rights Clinic. She added, “Not only will the Parole Board have questions about their readiness for release,” but petitioners “have to figure out where to live, find a job, and possibly complete additional programs the board wants them to take.”

According to Voukydis of CPCS, as well as Garin and Ryan Schiff, the attorney who argued Mattis in front of the SJC, the parole process is hardly quick or easy. All recent changes considered, training attorneys in the special needs of emerging adults will be crucial.

The status of parole

In 2016, under a previous chair of the Massachusetts Parole Board, Paul Treseler, the lifer parole rate was 18%, per Gordon Haas, who is incarcerated at MCI-Norfolk and keeps statistics on parole. Treseler has subsequently become a judge in Boston Municipal Court.

Since Tina Hurley was named chair of the Parole Board in November 2022, paroling rates for eligible lifers have improved significantly.

As of Jan. 25, 2024, 178 decisions had been posted for Hurley’s board. Per records kept by this reporter, about 57% of those who had hearings received positive votes.

The trend of increasing positive parole votes bodes well for the Mattis contingent. At the same time, those who petition for parole receive positive votes less often on their first appearance before the board. It can take several attempts to earn parole. According to advocate Jerry Breecher, who also keeps stats on the board, in the period from November 2022 to Jan. 25, 2024 (since Hurley has been chair), there have been 34 initial hearings. Records he sent to this reporter show that of those 34, there were nine who earned a positive parole vote, or 26%.

Those eligible because of the Mattis decision will face the Parole Board for the first time. Shawn Fisher and other lifers at Old Colony are planning to help prepare newly parole-eligible men for hearings by sharing the perspective of those who have been through the process. In an email, Fisher relayed a notice he posted at his facility (see inset).

Emerging adults, just like juveniles in the commonwealth, will be guaranteed counsel for their hearings. That is not true for all who appear before the Mass Parole Board. But according to CPCS, people with certain mental health diagnoses, and “prisoners with disabilities who require assistance to access a fair hearing,” can also be appointed counsel by the committee’s advocacy unit. Garin said appointed counsel for murder parole cases in Mass are paid $120 per hour, compared to private litigation lawyers whose average compensation is more than four times that amount.

In a phone interview, attorney Ryan Schiff said part of the challenge is answering the question, “How can [we] help illuminate a particular emerging adult’s circumstances?” For example, he asked rhetorically, How does an attorney represent to the board the specifics of a client “who commits a murder at age 20 and was drinking alcohol with friends who encouraged him to go after a ‘perceived enemy?’”

The training, unpacked

Voukydis said she expects the 10-hour training will be significant for at least 40 attorneys. It will be recorded, and participating lawyers will be able to access the videos on their own time. She added, “Many cases won’t go forward before six months due to the preparation needed.”

In an interview for this article, Garin said that “many very experienced criminal defense lawyers have not done work in parole.” She has taught and supervised hundreds of law students representing lifers at parole hearings, and recently taped several portions of the 10-hour training. Garin added that in order to help lawyers better understand the process and to illuminate “the difference between those who commit crimes as emerging adults and others they may have represented,” it is important “to educate [attorneys] about the law and practices regarding parole.”

The Northeastern professor said that she expects a relatively wide range of attorneys to take part in the professional development, from those “who have done lots of parole cases,” to some “who already represent their emerging adult clients,” and others who “are very interested in learning how to use Mattis and plan to take on cases.”

Part of the training will involve Ryan Schiff explaining how to apply the science behind the SJC ruling at parole hearings.

“Advancements in scientific research have confirmed what many know well through experience: the brains of emerging adults are not fully mature,” SJC Chief Justice Kimberly S. Budd wrote in the landmark decision. “Specifically, the scientific record strongly supports the contention that emerging adults have the same core neurological characteristics as juveniles have.”

Research indicates that this cohort, similar to juveniles, have developing brains that are not as fully-formed as those of adults. Thus, those in the 18-to-20 range can be reckless, impulsive, involved in risky behavior, and influenced by peers. They also “lack the ability to extricate themselves from horrific, crime-producing settings.”

Schiff’s part of the training will explain why it is important to hire an expert, often a forensic psychologist, “to help the board understand how an applicant’s age led to their crime.” His section will delineate how experts apply brain science and developmental psychology for emerging adults and will elaborate on risk-assessment tools to gauge their clients’ propensity for violence in the future. Schiff said some measurement tools are more effective than others.

Reached by email, Attorney Lisa Newman-Polk noted that she will provide information for the trainings about the Mass Department of Correction’s impact on parole attorneys—“especially related to classification, treatment, programming, and discipline charges, as well as [to methods of] advocating for clients inside.”

More board members needed

It is not yet clear how the Parole Board will arrange hearings for emerging adults. Some speculate that those prisoners held the longest will get hearings first. Others wonder how a six-member board will manage to fit Mattis cases into its currently packed calendar.

Advocates, as well as some legislators and members of the Governor’s Council, have urged Gov. Maura Healey to fill the seventh spot as soon as possible, citing the uptick in the body’s workload. As we reported last year, the board not only held more than 3,000 parole hearings in 2022 for lifers and non-lifers, but in its other role as the Advisory Board of Pardons, it will now review more commutation and pardon petitions, per new clemency guidelines.

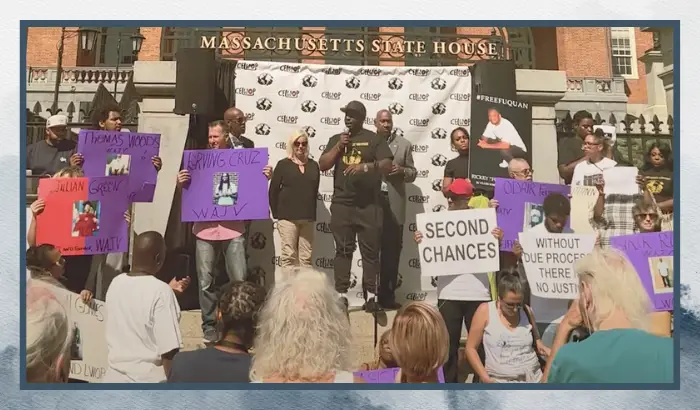

At a hearing held before the legislature’s Joint Committee on Public Safety and Homeland Security on Jan. 23, a number of people questioned whether or not the board should be expanded—especially in the context of the Mattis decision.

It was a historic hearing—the first for this committee featuring women and men from behind bars. At least 30 incarcerated people spoke on a number of bills, and many on behalf of others at their institution.

Abiona Sharpe, housed at MCI-Norfolk, said that he was testifying on behalf of six others. He supported legislation promoting An Act to Promote Equitable Access to Parole; versions filed by Sen. Liz Miranda and Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa that would, among other things, expand the board from seven to nine members, and require that candidates have at least five years of experience in psychiatry, psychology, social work, or the treatment of substance-use disorder. One board member must be formerly incarcerated and have completed the parole process.

Last year, Sen. Jamie Eldridge and Rep. Mary Keefe sent a letter to Gov. Healey saying, “An essential lived experience that has too often been excluded from the Parole Board is one that can only be derived from a period of incarceration.”

Sharpe said he came to prison as an adolescent. With 15 years behind him, he has been able to see the parole system up close, and expressed gratitude to the current board chair, Tina Hurley, for her “attempt to be more forward thinking.” Sharpe asked lawmakers to continue that progress, in part by expanding the Parole Board to nine members, and “lessening the workload.” He also said the parole bills before them would add diversity to the panel, and help address structural racism.

Remaining complications

Advocates including Voukydis and Garin are concerned about some of the difficulties that will face the board with newly parole-eligible applicants. Some questions remain.

It is not uncommon for a prisoner to be serving a consecutive sentence along with LWOP. What will the board or the courts do about those who received such punishments, i.e. a natural-life sentence to be followed by a sentence of 40 to 50 years?

Furthermore, many Mattis clients may have disabilities which could complicate their parole-planning process. According to a federal report published in 2021 by the Bureau of Justice, “the most commonly reported type of disability among both state and federal prisoners was a cognitive disability (23%), followed by ambulatory (12%) and vision (11%) disabilities.” How will they be handled for these hearings?

Parole applicants can also wait months for help with violence prevention and addiction, which will present another challenge. Because of the DOC’s policy, many programs have not been available to first-degree lifers.

“Even for people who are going to be released, the wait list is long,” Garin said. “To continue strong representation at parole hearings, we need a steady stream of highly qualified lawyers.

“That means we need legislators’ support in the budget to fully fund all appointed counsel.”