While Massachusetts seeks a contractor to provide healthcare services for people in state prisons, advocates are pushing for stronger oversight of private operators as incarcerated people describe “deplorable” neglect and mistreatment

By Dan Atkinson and Jean Trounstine

For the past six years, Massachusetts has paid more than half-a-billion dollars to a private, for-profit contractor to provide healthcare in its prisons—a service that incarcerated people say routinely ignores their medical plans and conditions, leading to severe health problems.

One incarcerated person described being told by a doctor that a hemorrhage “would eventually correct itself.” Another said that they were “worse off” after treatment for a knee injury. “My experience with the mental health department is deplorable,” a third said in an interview for this article.

The contractor, Wellpath, has come under increasing scrutiny—in other states, and here in Massachusetts, where the state agreed to give Wellpath millions of extra dollars to hire workers it’s already contracted to provide. Still, prison healthcare advocates say the problem is bigger than just one provider.

Wellpath’s contract with the Department of Correction expires in July, and state officials have put prison healthcare services for more than 6,000 incarcerated people out for bid. The solicitation is more than 200 pages long, but it’s missing crucial elements and requirements that could improve health for and prevent abuses of the incarcerated—and help prevent any for-profit health care provider from putting profits over prisoners, advocates argue.

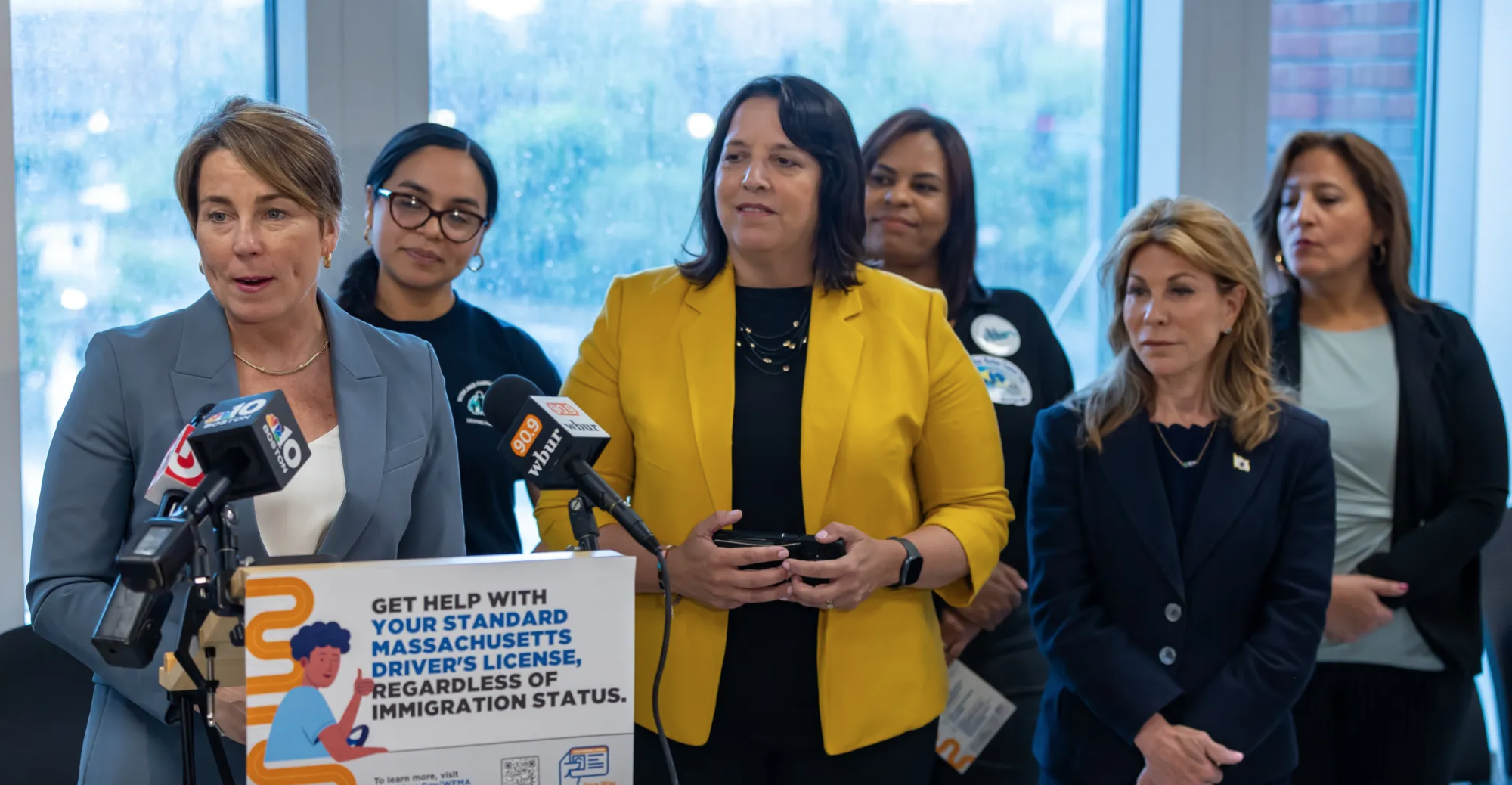

At a rally outside the State House last weekend, speakers described how they and family members did not receive basic medical care while in prison, in some cases leading to major health problems. While the group leading the rally, DeeperThanWater, promotes prison abolition as the ultimate solution to healthcare concerns, members said that in the short term, it could help to require an oversight board that includes incarcerated people, and to issue higher fines for failure to follow treatment plans.

“If these processes aren’t in place, people in prisons don’t have access to healthcare on a very basic level,” DeeperThanWater member Hannah Michelle Brower said. “That’s why we see these as needing to be written into the [request for proposals], so there’s no excuses for the provider.”

“A decline in quality of care”

DOC hired Correct Care Solutions to run its prison healthcare system through a competitive bidding process in 2018. That organization subsequently merged with Correctional Medical Group to create Wellpath, which is now owned by the private equity firm H.I.G. Capital.

Wellpath is the largest prison health provider in the country—it is currently contracted to serve approximately 275,000 incarcerated people at 500 facilities. Per a Project on Government Oversight report in 2019, by that time, Correct Care Solutions had been sued more than 1,000 times by prisoners or their families for negligence and medical malpractice.

DOC has paid Wellpath in excess of $666 million over the course of the Mass contract, according to state records. The agreement originally ran for five years and was renewed in 2023—but while DOC had the option to renew again, it instead put the entire prison healthcare contract out for bid again late last year.

This all comes in the wake of a federal civil rights investigation into DOC that began in 2018. The US Department of Justice looked into claims that prisons were placing incarcerated people with serious mental illnesses in restrictive housing for a prolonged period of time, and later expanded the investigation into whether the DOC furnished adequate mental health care and supervision to prevent self harm.

At the end of 2020, the Department of Justice concluded it had “reasonable cause to believe that conditions in MDOC prisons violate the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution through MDOC’s alleged failure to provide constitutionally adequate supervision and adequate mental health care to prisoners in mental health crisis, and its alleged placement of prisoners in Mental Health Watch under ‘restrictive housing’ conditions for prolonged periods of time.”

DOC disputed the DOJ findings, and the agencies came to a settlement in 2022 in which the state did not admit to any wrongdoing, but agreed to meet more than 100 policies and protocols laid out in the settlement in order to ensure adequate treatment. The settlement established a Designated Qualified Expert to monitor the state’s prisons over the next four years to determine if the DOC and its healthcare provider are following the requirements laid out in the settlement. The most recent report, released last September, noted the department and Wellpath are in compliance with some and partial compliance with other policies, but noncompliant with a dozen orders, particularly around the required staffing levels.

Brower of DeeperThanWater said the DOJ’s investigation reflects the results of a survey her group conducted over the past few years, in which they reached out to 141 incarcerated people in state prisons. Among the findings: almost 80% said they had a medical condition that is being ignored by staff; only 25% of people with a recommended treatment plan said it was being followed by medical staff; and nearly 20% of respondents said they were forced to receive medical treatment they did not want.”

That survey was cited by Senators Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren in a letter they sent to Wellpath in December, highlighting concerns about understaffing and mistreatment of incarcerated people with mental health issues and noting Wellpath’s contract will be up in July 2024. In the communication, the senators ask for Wellpath to provide information on its staffing, budgeting, lobbying of politicians, grievances and lawsuits filed against the corporation, and detail about services it provides.

“As members of the congressional delegation from Massachusetts, we are especially concerned with reports of Wellpath’s failure to provide proper care for incarcerated people in our state,” the senators wrote. “Anecdotally, incarcerated individuals in Massachusetts have noticed a decline in quality of care and longer delays since Wellpath took over the state’s carceral healthcare from the previous providers.”

“They seriously had me suffering in pain when I didn’t have to be”

The stories prisoners told BINJ describe more than just a decline in care. They’re descriptions of dismissal and mistreatment that show how their lives have gotten worse because of medical neglect.

Derrick Washington, currently incarcerated at MCI-Shirley, is a documented asthmatic. In an

email, Washington laid out why he is suing Wellpath for what he described as “egregious

conduct” while he was at Souza Baranowski Correctional Center (SBCC) in 2020.

In January 2020, more than 100 prisoners were viciously beaten and attacked after an assault on a corrections officer at Souza, according to a federal lawsuit. Washington alleges SBCC’s Wellpath director “authorized officers to spray me with chemical agents and refuse to give me my asthma inhaler.” He added, “I experienced life threatening, recurring asthma attacks, dizziness, and difficult breathing for one-and-a-half weeks.”

Then in March of that year, during another skirmish, Washington relayed that after he was beaten “relentlessly,” while officers sprayed him with “canisters of chemical agents,” leaving him in “a pool of my own blood.” Nurses didn’t allow him “to bathe or wash the chemical agents from my body,” Washington wrote.

At a facility across the state, several men at Old Colony Correctional Center (OCCC) in Bridgewater have echoed similar concerns about Wellpath.

William Soper, who suffered from sexual, physical, and mental abuse before he came to the residential treatment unit at OCCC, wrote in an email that Wellpath “waited too long to send him out for treatment,” which caused “permanent vision loss” in his right eye.

It wasn’t just delays, Soper said, but his sick call slips were ignored for three months although he continued to complain of “blurred vision.” Finally, when he got to see a Wellpath doctor, he was told he had a hemorrhage behind his right eye. Soper said the doctor claimed the hemorrhage “caused blood and fluid to build up,” but assured him “it would eventually correct itself.” Soper wrote he was supposed to see an optometrist, which never happened, was given shots in his eye which did not do much, and ultimately wound up with only “peripheral vision” in his right eye and “no depth perception.”

“Regardless of being in prison or not, I’m still a human and deserve human care,” Soper said.

Mark Taylor, also housed at OCCC, said in an email that he was another “victim of delayed treatment and misleading statements.” Taylor stated that he’s “worse off now” than before treatment for his medical issues. The first involved a total knee replacement he needed but never had. Instead, Wellpath tried to “repair the tear of the medial meniscus,” Taylor said. That “did not work,” he said. Taylor “was given a cane.”

The second issue involved the removal of a lipoma which left him with a multitude of complications such as “nasty scarring, infections, hematoma, numbness, and burning.” Taylor added, “I have no one to turn to.”

“Wellpath is not providing adequate medical care,” said Charles Dyous, a prisoner at OCCC who is currently fighting what he says is a wrongful conviction. In terms of medical care, Dyous said it took three years for Wellpath docs to finally diagnose him with a torn meniscus that requires surgery.

“It is 2024 and I still haven’t had that surgery,” Dyous wrote. He also suffers from untreated GI issues and improper support for what he described as “a bilateral foot drop requiring me to wear medical ankle braces, socks and shoes.”

Medical neglect at OCCC has also reportedly plagued Umar Salahuddin, Sam Smith, and Malachi Yahtues, who all say Wellpath ignored their grievances. Like with Soper and Taylor, they said the medical staff needlessly prolonged the time it took to respond to their concerns.

It took Salahuddin months to get an MRI after injuring himself working out, only to be mistreated with physical therapy for what ultimately he discovered was “a torn hip socket and two torn groin muscles.” He wrote in an email, “They seriously had me suffering in pain when I didn’t have to be.” He has yet to receive any treatment that would alleviate his pain, Salahuddin said. “Everyone knows what the problem is,” he added, “and physical therapy won’t fix that.”

Smith’s troubles began in 2018, when he was sent to the health services unit (HSU) for what he said was “a small scratch measured out to be no more than 1.3 inches long.” Ointment and Band-Aids seemed to provoke the scratch and, 90 days later, still with no treatment, “the wound on my leg had changed colors three or four times.” Another delay, and he got infection medication, and days later, was finally sent to Shattuck Hospital where he ultimately had to stay for a month. Since then, Smith has had constant flare ups with infections. He wrote in an email, “My temperature skyrockets out of nowhere.” The problem, he noted, has not been resolved.

Yahtues, a transfer to Massachusetts from New Hampshire, said he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and treated with Wellbutrin for depression while incarcerated in New Hampshire. But when he got to Mass, he wrote in an email, doctors regarded him as a “crash-test dummy,” switching him from medication to medication, none of which worked.

“My experience with the mental health department is deplorable,” Yahtues wrote. Like the others who spoke for this article, Yahtues said that Wellpath has caused serious harm to prisoners in the Bay State.

At last week’s rally, Angelia Jefferson described seeing fellow incarcerated people mistreated, and also recounted her own medical neglect while she was incarcerated at MCI-Framingham. Now a staff member with Families for Justice as Healing, Jefferson said she and other women were pressured to take doses of suboxone and methadone for pain management, leading some to become addicted to painkillers.

“I chose not to take them, I chose to deal with the pain and just hope and pray that one day I could get out and get everything fixed,” Jefferson said. She recently got reconstructive surgery on her foot after being given a medical boot as treatment in prison.

Prisoners have to file “sick slips” to request treatment, and those previously cost $3, Jefferson added. And the slips are often ignored, or not responded to with urgency.

“We’re giving you our money but you’re not giving us what we need,” Jefferson said. “Wellpath is the worst, out of 10 nurses you get one that genuinely cares but they can’t do much. They do not do the job they are paid to do.”

“Quality and compassionate care”?

Wellpath did not respond to a request for comment. In a statement, a DOC spokesperson said the “Massachusetts Department of Correction remains deeply committed to providing comprehensive health services to the approximately 6,000 incarcerated individuals in our care. … In correctional settings, the success of the rehabilitative mission relies on a system’s ability to provide quality and compassionate care. We continue to work in close partnership with our contracted medical provider to address the challenges of caring for a population that often has complex and significant health needs.”

But as the DOC searches for a new medical provider, it has ignored basic recommendations that would make sure prisoners get proper care, Brower said. The department paid researchers at the UMass Chan Medical School $510,000 to help write the bid solicitation for prison health services, and Brower said DeeperThanWater suggested numerous requirements be enshrined in the solicitation, including:

- Having an oversight board with incarcerated people on it

- Letting incarcerated people see providers outside of the selected contractor

- Including language requiring the contractor to respond to sick slips in a timely manner

- Requiring higher fines for not following treatment plans

- Requiring sufficient staff and staff with valid credentials

“We came up with revised language, we made it as easy as possible for them to add it to the [request for proposals],” Brower said. “We’ve written out language requiring response to sick slips and to provide care in a timely manner—neither of those is happening right now. … These feel like very basic processes that should be followed by anyone.”

The bid solicitation doesn’t have DeeperThanWater’s recommendations, but Brower said the document was clear about the DOC’s priorities of saving money. When describing the contractor’s responsibility to prisoners needing Specialty Care services, the RFR states care must be provided “in a timely and cost-effective method and consistent with professional standards of quality care.” It continues, “These Services shall be provided on-site to the extent practicable and off-site only as necessary. Within the first 12 months of the Contract, Contractor shall review the current system of specialty clinic utilization and may propose alternatives that may be more cost-effective.”

“They set their priorities and the top priority is cost savings,” Brower said. “Their priority is to save money, this needs to change immediately.”

“Pocketing the money”

That prioritization of cost over safety, Brower said, is also reflected in staffing. While Wellpath is required to provide an adequate number of workers, and the request for proposal makes similar requirements, Wellpath and DOC can add staff, move staff around, or reduce staff at various facilities if both parties agree. A 2019 contract amendment shows MCI-Concord gaining a part-time dentist at the same time MCI-Framingham lost that position.

The DOJ settlement named staffing as a major issue, and the September Designated Qualified Expert report noted that 33% of mental health staffing positions were unfilled as of last January. A DOC spokesperson said as of December, 81% of Wellpath’s positions are filled across departments.

In another amendment to the existing contract from January 2022, Wellpath is described as “facing the immediate challenge of retaining, recruiting, and hiring healthcare staff in the current climate,” because “local market midpoint wages have increased approximately 15 percent in the last year, as opposed to historical 3 percent COLA increase for the subject contract.” So with a market demanding higher wages for services it was contracted to provide, Wellpath hit on a solution—get more money from the state.

The amendment reads: “DOC shall compensate Wellpath up to $3.2M over the six-month period of December 2021 through May 2022. This compensation shall be utilized solely for recruitment and retention incentive bonuses paid directly to specific Personnel as defined by DOC and Wellpath.” A DOC spokesperson did not immediately have information about which personnel received how much money in bonuses.

Brower questioned the extra pay for a company already getting $120 million a year from the state: “They’re already pocketing the money they’re making—they shouldn’t need extra to provide additional medical neglect,” she said.

Brower said DOC can still amend its bid solicitation through Jan. 17 in order to add the stronger staffing and other requirements suggested by DeeperThanWater. But regardless of whether that language is added, Brower said she hopes Warren and Markey continue to shine a light on prison healthcare and fight for better treatment.

“This is an issue often so invisible to the public,” Brower said, “so we’re hoping they continue to press not just Wellpath but DOC to make changes to ensure the situation with medical neglect is addressed.”