Talking vinyl, Boston mob and music history, and sex toy sales at an enduring Boston record shop

Looney Tunes Records is a cauldron of music history and vinyl, cooked up by a mad scientist.

Wedged between a hardware store and a Chinese restaurant, the Allston shop’s graffiti-covered exterior makes it easy to miss. The entrance is tucked beneath a café, across from a hair salon.

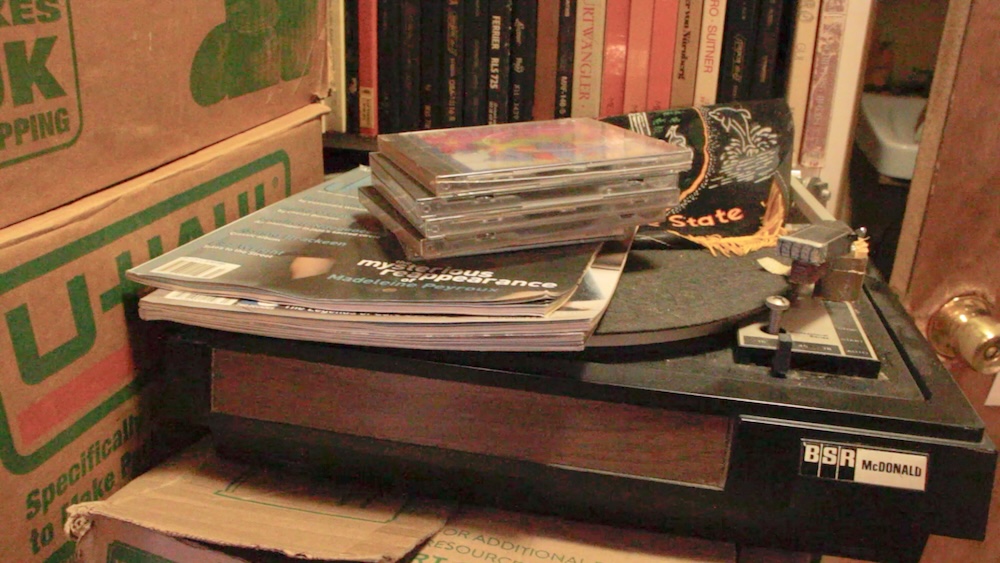

Inside, the world narrows to rows of sound, shelves packed with vinyl in controlled chaos, record stacks spilling onto the floor. A cat slinks through aisles of teetering cardboard boxes; a jazz record spins from a corner setup, its warm crackle filling the dimly lit basement where posters, string lights, and album art blanket every surface. A skeleton, decked with lanyards, headphones, and a baseball cap, stands guard in the middle of the store.

This strange temple of analog sound is run by Pat McGrath, a wiry man with wild hair, dry wit, and the twitchy energy of someone who hasn’t heard enough. He’s been running record stores in Boston since the early 1980s, when he bought into the original Looney Tunes on Boylston Street. That store ran for decades. The current incarnation, equal parts shop, museum, and personal archive, opened six years ago in this subterranean space.

“I have a dingy basement full of records that I try, through my enthusiasm, to sell to people,” McGrath says. “So that they, too, may have these sounds etched in plastic nourish their souls and free their minds from the tyranny of conscious thought.”

Genesis of a vinylphile

Growing up on the Ohio-West Virginia border, records were one of his few portals into a wider world.

“There weren’t many windows,” he recalls. “Three TV stations, four if you count educational. You could read books, go to the movies, or listen to records. My mom had a few. I found them fascinating.”

By high school, McGrath was working in a record shop. That pattern continued into college, with short detours into landscaping and, briefly, selling sex toys.

“Surprisingly dull,” he says. “You’d just be counting boxes of rubber dicks. Seven, eight … very uninspiring.”

Music was the opposite—unpredictable, endless, alive.

“Any kind of art has an infinite variety. You never get bored.”

McGrath’s stories bounce between the absurd and the unbelievable. In one, he recalls working at Strawberries, the chain once owned by Morris Levy, a record mogul with ties to the Genovese crime family.

“These guys were as cliché a gangster as could be,” he says. “You didn’t ask too many questions.” According to legend, one deal gone wrong involved trucks filled with garbage records and a buyer who ended up beaten in a warehouse.

“Allegedly,” he grins. “At least that’s what I was told.”

From the stage to the stacks

Despite, or perhaps in part because of its eccentricities, the Boston music scene of the 1970s and ’80s thrived.

“Every club had its niche,” McGrath remembers. “The Rat was punk. The Jazz Workshop was jazz. … Between here and Comm Ave, you had maybe seven venues with live music. Now? Maybe three or four.”

McGrath played at Johnny D’s in the mid-’80s, even opening for Faith No More and Throwing Muses before either band made it big. But as a performer, he took a winding route to calling himself an artist.

“To tell you the truth, I didn’t consider myself a musician until I was 25 or 26,” he says. “Before that, I was just dabbling. I wanted to be one, but I wasn’t working towards it, I was imagining it more than anything else.”

Years of listening to virtuosos left him discouraged. “I’d think, I can’t do this. I’ve got to quit. But then I realized that technique and virtuosity aren’t the only routes to expression.”

He gestures to a white Epiphone acoustic guitar placed on a stand nearby: “Want to hear something?”

McGrath picks it up and begins a soft rendition of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” by The Beatles. The sounds drift through the store like incense, wrapping around dusty corners and forgotten albums. It isn’t perfect, but it doesn’t have to be.

In this world, perfection’s not the point.