Reclaiming civic power from outside developers

In February, eight members of the Cambridge City Council voted to pass a sweeping upzoning ordinance that dramatically alters the character of our residential streets. Residents were largely shut out of the process. Local neighborhoods—those most impacted—were told to stand aside while outside developers, political donors, and self-styled experts redefined our city without us.

This is not just a Cambridge story. It’s happening in Somerville, in Newton, in Arlington—and across the Commonwealth. Whether the rhetoric is about affordability, sustainability, or “smart growth,” the result is often the same: top-down planning rewarding outside “bottom line” beneficiaries.

As a longtime Cambridge resident, civic leader, and historian of art and architecture, I’ve spent my life thinking about the built environment—not just what we build, but who we build it for. Cities are not blank slates or development zones. They are living, breathing cultural fabrics, shaped by the people who inhabit them. When we let speculative capital override community voice, we don’t just lose historic houses or trees—we lose trust, rootedness, and the ability to make collective decisions about the places we call home.

We are told that public participation slows things down. But what’s the rush—when the stakes are permanent? Good planning takes time. And it starts not with zoning overlays or investment portfolios, but with listening.

The question I pose is simple but urgent: Who owns the city?

If we mean ownership in the deepest sense—stewardship, responsibility, belonging—then it must be the people who live here, not those who profit from transforming it.

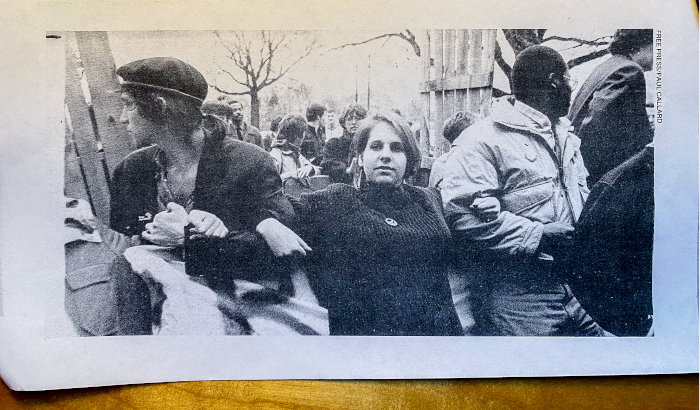

Across Massachusetts, residents are waking up. They’re reading the fine print, attending hearings, organizing neighbors. They’re saying no—not to growth, but to the wrong kind of growth. And they’re saying yes—to democratic process, to preservation, and to policies that reflect the complexity of actual communities.

Many of us would like to steer away deregulated, market-driven housing approaches that too often have not worked in other cities to bring down housing costs. These approaches often enrich developers and result in larger luxury single family homes and high-rises. Most importantly, these policies simply will not provide the affordable housing they promise, especially for those at the lowest income levels. One model of what does work is reflected in a recent decision in Berkeley, California to add new housing specifically for teachers. Read more here.

My broader civic interests lie in the realities and politics of planning, the language and outcomes of development, the erasure of community voice, and alternatives that give power back to people. I write from Cambridge, but this is not only about Cambridge. Because what’s at stake is much broader: the future of our cities as civic, cultural, and human places.

If we want to preserve the soul of our communities, we must reclaim the ground beneath our feet—street by street, vote by vote, plan by plan.