An interview with Eoin Higgins, author of ‘Owned: How Tech Billionaires on the Right Bought the Loudest Voices on the Left’

Those who barely pay attention to modern political discourse via rapid and vapid social media mutiny may not notice the phenomenon with the close gaze of daily readers and online combatants, but pundits change, their voices morph. It’s why journalists often get friends asking us questions like, What the hell happened to that Matt Taibbi guy? Didn’t he used to, like, speak out against insane bigots and the one percent?

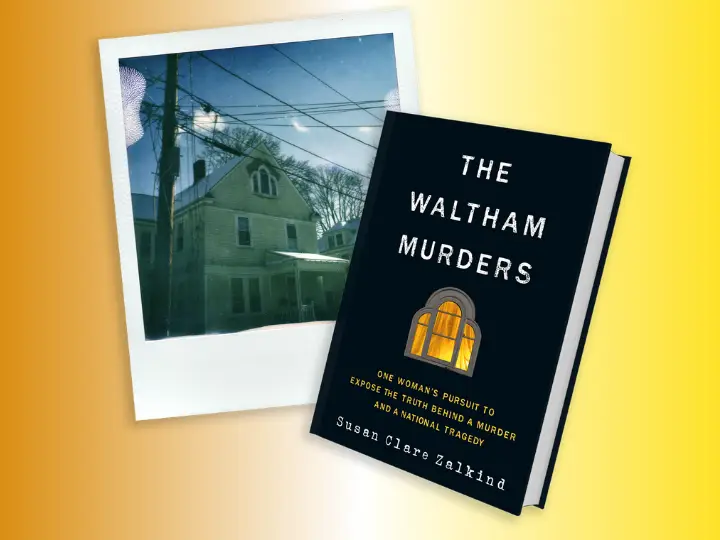

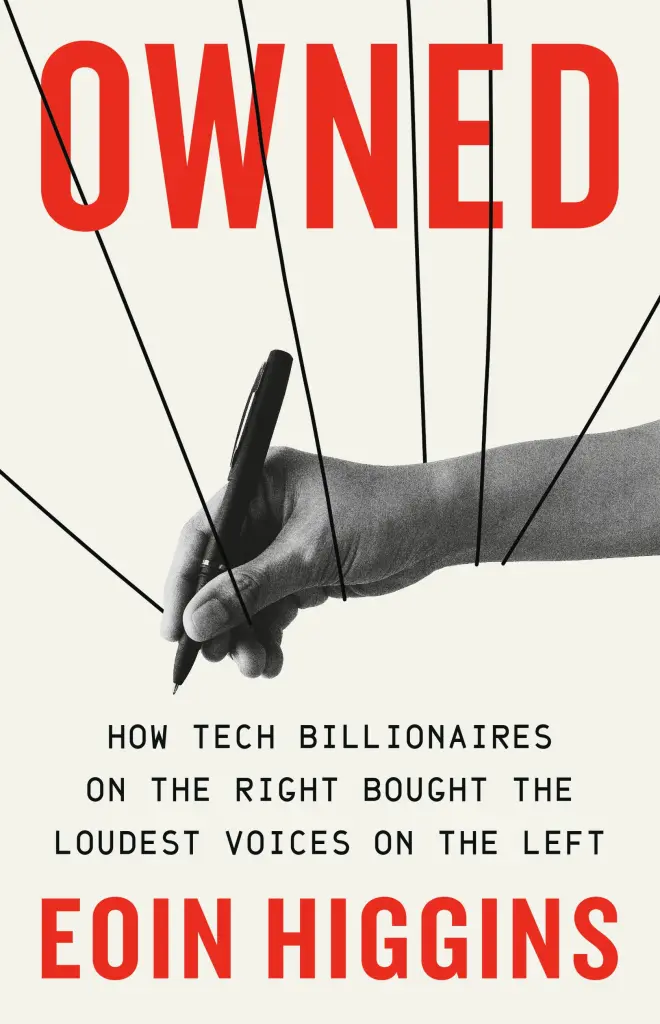

For reporter Eoin Higgins, it wasn’t enough to ask questions—or even just to closely watch the rightward shift of journalists like Glenn Greenwald and Taibbi. Higgins has spent years in the polemicist arena, trading barbs with the best (and worst) of them, and took the deeper plunge. His new book, “Owned: How Tech Billionaires on the Right Bought the Loudest Voices on the Left,” doesn’t just impugn the messaging and motives of the aforementioned writers among others, but also examines the money and power which apparently lured them astray.

With Donald Trump in office and characters like tech billionaires Peter Thiel and Elon Musk in the forefront—in the case of the former, it’s more often his data-mining firm Palantir than the man himself making headlines—it’s no surprise that “Owned” is all the rage, earning props from left-leaning outlets like the American Prospect along with recognition up to the New York Times among others. We asked Higgins, who has written for the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, about all the juicy Musk stuff that the nationals are interested in, but also had the Berkshire County native walk us through his rise from a late bloomer in the scrum to the rare gladiator willing to challenge some of the most powerful people in tech and contemporary media.

CF: When you were putting the finishing touches on the book and looking at your publishing schedule, were you thinking of this as like a pre- or post-election book, and does that mean anything to you, besides from the pure marketing dynamic of it?

EH: This was my first book. My instinct, you know this, having edited me, is always to get it out as quickly as possible. But in this case, I was contracted to write it in August of 2023 and I delivered the first version of the manuscript March 1st, 2024. And then we edited it, and even then I was like, Do you think we can get it out before the election? I think this would be really important before the election.

As it turns out, they got it out as quickly as possible (Feb. 4). And I think that it was probably the best timing.

CF: It’s a great background on a lot of the characters that we’re seeing in the second Trump administration.

EH: I hear you, but I didn’t want to get too deep in the weeds with that stuff. … I didn’t think that Trump was going to win—not because I thought that [Kamala] Harris was a particularly strong candidate, but once it wasn’t Biden, I thought it was pretty much sewn up. I didn’t think that there was really much of a chance that Trump could do it. Obviously I’m wrong, but I didn’t know in the back of my head if I [acknowledged], If he does win, this book becomes a lot more relevant, like real fast.

CF: Let’s start at the beginning for you. Even as someone like me who worked with you when you were starting doing reporting that would lead to having a real national profile, it still seems this all kind of happened relatively quickly, but I know that from where you’re sitting, that’s probably not the case. Has this been a whirlwind for you? Or are you just in it day to day?

EH: I don’t know, man. I’m like a high school dropout. I dropped out of high school and I didn’t do anything for 10 years, and then I went back to college in my late 20s, and then I ended up getting my master’s, and then I couldn’t do anything with a master’s of history.

When the Intercept started, even though I wasn’t a writer or a reporter or anything, I do remember applying for a job there anyway. I just wanted to write. I always knew that I wanted to write. I was working as a bartender and I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, and my wife was like, You need to do something. You said that you want to be a writer, like you want to be a journalist, why don’t you just start blogging?

And so I started blogging, and that was about 10 years ago in March. And I started doing that, and I started applying to places, and I applied to this local paper called the Berkshire Record that was looking for a front desk person. It was just a way for me to do something in the Berkshires where there isn’t really much anyway. We went on vacation and came back and there was a message on my parents’ machine—not our machine and not my phone—from that paper saying, Hey, we don’t have this position available. But if you’re interested, we are looking for a reporter. Would you like to try that? And I was like, Yeah, sure. So I tried it and I fell in love with it.

Then I moved to the Berkshire Eagle, but the reason that I have a national profile, I think, is that it’s a couple of things. So one, while this was happening, in 2015 coming into 2016, when online writing and social media were really big, my friend Gabby Squailia, who is a writer and author in the Berkshires, was like, You should get on Twitter. You like to fight with people online. Why don’t you just get on Twitter and you can do it there and you can fight with people. And I was like, Okay.

And I started doing that. And I do enjoy arguing with people, so that was fun. And then I just started to build a profile, and basically I just pitched every single place I could possibly pitch. And I made a promise to myself, in the beginning, I was like, I will not work for free.

That’s my only thing, I won’t work for free. I’ll write for free for myself, on a newsletter, or like my website, but I’ll never write for somebody else for free. Because I have to treat it like a job. And so I did that, and I just pitched everywhere I possibly could, and I just patched together a living through freelancing for a long time, and that’s why I have the profile that I have, because I just wrote for everybody I possibly could. And then, the next time that I would come to them or come to anybody with something, my work would be stronger. And all the while, I was building up a social media platform. So that’s how I ended up where I am.

CF: It seems like the book is a combination of reporting that you did but also the situation you were in that led to this book—namely, writing for the Intercept at a time when Greenwald was sliding rightward. … But what ultimately led to this book?

EH: I was certainly influenced by Glenn, I think, a lot in my career, but first of all the fact that he, like me, didn’t go to journalism school. He had no background in it. I looked at that as a career model. I was like, if this guy can do it, I can do it. … He was a lawyer, I’m a historian. We both had an expertise that was somewhat related to journalism. And so we’re able to go into it and be like, okay, I’ll use that. And in the case of Glenn, yeah, I’d followed him online for a long time and interacted with him quite a bit.

I started writing for the Intercept as a contributor back in 2017, shortly before I lost my job at the Berkshire Eagle. My first story was the one on the free speech rally in Boston. … So I started writing for them, and I did some surveillance ICE documents and stuff for them, and I got some praise from Greenwald. After him, I think I was the first person in the US Intercept to write about [Brazilian politician Jair] Bolsonaro. And it plays into the narrative of the book. In 2020 I was working for Common Dreams, and that job ended and right after that I was approached by another reporter who was looking for a place to land reporting on this Alex Morse-Richard Neal scandal. … That’s the moment in the book, in the beginning, when [Greenwald] somewhat jokingly but in a praising way said that I should win a Pulitzer for it.

CF: And as for your relationship, you write that you ultimately got along with Greenwald while you were at the Intercept and your interviews in the book seem pretty cordial despite the subject matter. I definitely want to hear about that.

EH: So this reporting happened with the Alex Morse story and then, at the time, Glenn was doing a lot of media hits on Tucker Carlson, which I thought was a smart idea for him, but also I was willing to give him the benefit of the doubt. I remember messaging him a few times and being like, Hey, I don’t know if this is like the best thing, but whatever. I don’t think that you’re like racist or anything, but Tucker Carlson definitely is.

We weren’t fighting, we were just starting to have disagreements in our politics where we’re starting to really diverge. And then, after he left the Intercept, he just shifted to the right in such a noticeable way, and in what I consider to be a really transparently motivated way. … And so I felt like there was a lot of hypocrisy there, and I started to get annoyed. And then we just started to snipe at each other a little bit. And then I wrote this article for my Substack comparing his tweets about Fox before and after he started going on there, and it just showed very clearly that the positive posting about them increased in direct relation to him going on there.

And based on the strength of that, I was approached by Norman Solomon at the Institute for Public Accuracy. He asked me to write a few articles about Glenn’s rightward tilt. Those were articles about Glenn and Tucker Carlson and the Great Replacement Theory. And also Glenn’s transphobia. And then there was Glenn and Alex Jones, all of which kind of have been folded into the book.

I pretty much had the whole thing written. And then I went to the Cape for two weeks to finish it. And while I was there, I had set up an interview with Glenn, one of the last things I had before I filed. And so I sat there with him for two hours. He was in Brazil, I was in Massachusetts. And I just talked to him. I had this whole list of questions, totally cordial. Despite all the things that we’ve said about each other, it was totally fine. Like really pleasant conversation. Without that interview, I don’t think the book would be as strong as it is. It really forms the backbone to have him responding to a lot of this stuff.

CF: But I assume at the end there’s fact checks and everything else that comes with a book project. Was Greenwald available for all of that as needed? Or did he cut you off?

EH: The agreement we had was totally reasonable. He was like, I’ll totally talk to you. I just want to see the quotes that you’re going to use. I’m not going to tell you can’t use anything. I’m not going to ask for quote approval. I just want to be absolutely sure that if you’re quoting me, that there’s context. … I just don’t want to be quoted in a way that makes me seem like I’m saying something I’m not. That’s fair, I said.

CF: Has Greenwald reacted?

EH: I don’t think he’s seen the book yet, he certainly has not acknowledged it or anything.

CF: I don’t want to get sidetracked by it, but I was surprised that Christopher Hitchens didn’t come up.

EH: The first thing that I wrote for this book, the first little section that I wrote, was about Hitchens. I eventually ended up just discarding it for a couple of reasons. Primarily, I can’t stand Hitchens, I don’t find him particularly interesting. That’s why I didn’t do it. I really just don’t like him very much. I think he’s overrated, and fine, he’s a decent stylist, but I also think that he’s just a really repulsive individual.

CF: Back to what’s in the book though, it’s amazing how far getting banged up by the left can push some people to the right. Having learned what you learned, what do you make of how quick the left is to abandon someone like Taibbi?

EH: The real problem was with liberals, not with the left. Because what happened with him is he was writing about Russiagate and liberals didn’t like that. He tried to reset his relationship with them by writing this Eric Garner book, and then during the release, he gets fucked … with [right-wing rabblerouser Mike] Cernovich cynically using the Me Too movement to fuck him over. And, I’m not saying that the things that he wrote were, like, good or anything. … His behavior in Russia, also not good. But, it was certainly being used in a way that was not great.

But [Taibbi] did have a measure of support from the left in the beginning when this was happening. Mostly because people, even if they found his writing and his behavior back then repulsive, they did have an understanding that he was being ratfucked. And they did understand why it was happening. And that it was a coalition of far-right people who always hated him, and liberals who hated him for the Russiagate stuff. And they were working together to fuck him over. … To the extent that any of this stuff might be true or not, there’s not a lot of evidence for it.

It just seems like he is a bore and an asshole, but that’s not the same. … I think that the left rejecting him comes later. And that comes when he shifts to the right because of this. And then starts endorsing further and further crazy conspiracy theories. To the point that during COVID, he’s completely lost his fucking mind. And that’s a big problem. … I went on his page last night, and it was just like a bunch of anti vaxx shit. Just Rob Schneider level.

CF: Were these people progressives to begin with? You really nailed down a lot, I think, on Greenwald just loving that First Amendment, just basically a First Amendment shit fight, but what’s really going on here?

EH: I think there are a couple of things. Certainly the motivations of somebody like Taibbi or Greenwald are going to be different from the motivations of somebody like [venture capitalist Marc] Andreessen, right? Andreessen’s a multi billionaire. … I think that Taibbi’s [motivation] is maybe equally financial and equally [that] he’s a culture warrior on the right now.

Glenn I see as more cynical. I think that his turn is a little bit more about self preservation within his career, and I think that he just tends to be a smarter person in general. … But it’s always about money with these guys, ultimately. Same thing with [Peter] Thiel. They’re conservatives, but they’re leaning into the current far-right movement because it’s an acceleration of their pre-existing political beliefs.

CF: But does it mean something to them to have somebody who’s had prestige on the left like Taibbi as opposed to any old schmuck? They could try out 150 wannabees a year, and maybe 10 end up being the new conservative celebrities. Why poach from the left? Is it worth it to still get that P.J. O’Rourke factor in 2025?

EH: That’s good, I should have made that comparison in the book, PJ O’Rourke’s a good one. Yeah, I think that their prestige does matter. I think that if you are promoting a video site, for example, as an alternative to YouTube, because YouTube is not boosting conservative voices enough, not boosting the kind of politics that you want, then you want something that’s going to attract other creators that can get a base, and that’s why you get Glenn Greenwald to come over to Rumble, right? If you want to get out a message about the social media company you just bought, and to get people to get mad at the former owners and think highly of you—and also to make it seem like the Democrats are working alongside social media to censor people—then you get somebody like Matt Taibbi, who has credibility.

CF: Clearly we’re all now living in a Peter Thiel and Elon Musk world, so please address that. I’m not going to read the zillion other books about them, but the way that the relationship between them comes up in the context of your book seems especially interesting.

EH: Thiel has a dominant relationship with Musk. They started PayPal together, or technically, Thiel started it, but they needed each other basically to make PayPal work. Thiel was always the more dominant part of that relationship.

Thiel is an ideological true believer. And that’s one of the reasons why I feel like he’s a little hesitant to publicly embrace Trump. Because he’s such an ideologue, and this I’m just hypothesizing here, but he doesn’t want to embrace Trump because Trump is not going to really ideologically be perfect, if that makes sense. Musk is much more valuable. His politics, they may come and go. He said that he sat in line for hours to shake Obama’s hand back in the day. He embraced liberal culture for a long time, when that suited him, and then he didn’t once it didn’t. If Harris was president, I think it’s quite likely that Musk would be at least tempering some of the stuff he’s doing now, but because it’s Trump, and Musk has all this access to him, he did that neo Nazi salute. And he wouldn’t be doing that if Harris was president.

CF: On the media side of things, I think with Thiel, there is of course the Gawker situation, and the war he waged with them over personal grudges. In setting out to show that connection between media and tech, where did you go looking for answers and what did you find and what did you not find? And how much of that gap are you filling with this book?

EH: When it came to this stuff, [former Gawker site] Valleywag had covered [Thiel]. I had a few books that I used as reference points, but for the most part, I was just reading everything I possibly could find archived—old Gawker articles, old articles from the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, wherever. As far as the amount of books that I cited for this, probably between 40 and 50. The amount of articles is in the hundreds.

But what I was trying to connect … I wrote this article for Business Insider, an opinion piece from back in 2021 (“The media landscape shifted under Silicon Valley’s feet, so now they’re trying to silence criticism”). This is like one of the central pieces of the book, the beginning of this idea. It’s that Silicon Valley billionaires did not like [when] online media started to turn against them and to report on them critically. And so what they want to do is they want to create their own alternative media ecosystem that essentially acts as their sophisticated stenographer PR.

That’s what they want. That’s where it started, where it ended up is now they have this, and I really dislike using this terminology, but almost like an influencer campaign, where now they have certain ideological beliefs that they want to promote. And so people who are going to repeat that kind of stuff are allowed to promote it. Does that mean that they agree with everything that the people who are benefiting from their largesse are saying? No, I know that they don’t. For example, I’m sure they hate a lot of the things that Greenwald says about Palestine, right? But I don’t think that matters. Because what Greenwald is doing is he’s disrupting the media model that they don’t like. And that’s the thing that they really want to happen.

CF: It’s all about your enemy getting shit on.

EH: Yeah, it doesn’t mean that mainstream media is like some amazing good thing that needs to be protected. But what it means is you have to look at the reason that they’re opposing, right? These guys are not opposing it because they want real independent media that will actually act independently. They want the exact opposite of that. Their problem with mainstream media is not the fact that it exists and that it’s powerful, but it exists and it’s powerful—and it targets them.