“Our watershed is connected, and any one individual impact makes a massive difference to people who are even a couple towns away.”

Ipswich, Mass. – Shendel Bakal bought an abandoned farm in Ipswich in 2016 with dreams of starting her own business cultivating organic produce. She never expected that farming in a coastal town would mean fighting a relentless battle against drought.

“[My partner and I] wanted to grow produce from the land that’s currently existing and has been in operation for maybe a century,” said Bakal, owner of Twin Birch Farms . While Bakal, 70, says she has no intention of selling her farm, she’s significantly cut back on what the land can produce.

“It kills me to let the land go,” she said.

The 2022 drought, one of Ipswich’s most severe, proved “excruciatingly expensive” for Twin Birch Farms, Bakal said. And she’s been trying to recover since.

“We have tried to grow crops that are more drought resistant and don’t require a lot of water,” said Bakal. “However, we aren’t able to water the crops fast and long enough”.

The operation receives its water from a pump from a nearby pond, but it is very labor intensive and expensive. Other means of water supply are an expense they can’t afford.

The farm used to supply produce to a number of local restaurants, but recently, they have been unable to support the demand. As a result, the restaurants have turned to bigger farms with more financial support, a devastating blow for a small-scale operation already struggling with rising water costs.

Despite applying to a state aid program, bureaucratic hurdles left her desperate.

“I’ve filled out enough papers to build a house,” she said.

Bakal’s story is a microcosm of a larger crisis that is unfolding across New England, a region celebrated for its vibrant autumn foliage, dense forests, rich soil, and abundant water sources. Over the past decade, New England has experienced historic drought conditions, drastically changing its landscape and economy.

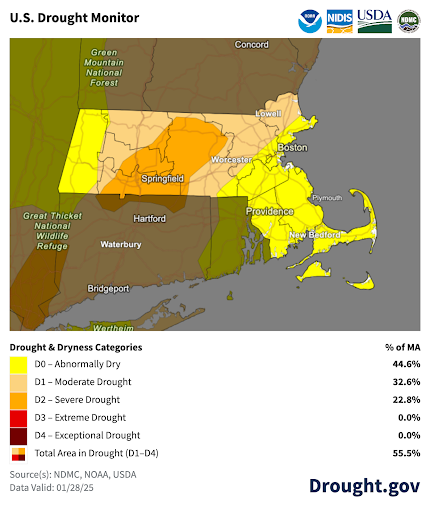

More than 3.2 million Massachusetts residents now live in drought-stricken areas. This unusual climate has posed disastrous effects for businesses that rely on fertile lands and plentiful water for its agriculture.

Click here for up-to-date Mass. drought data: https://www.drought.gov/states/massachusetts

Even rain and snowfall, which has downgraded some regions from a Level-3 Critical Drought to a Level-2 Significant Drought, hasn’t fully fixed the problem. Streamflow remains below normal in much of the state. This has resulted in dry conditions in brooks, ponds, and streambeds, as well as limited fish passages and exposed beaches and sediments. Even flash droughts, which are frequent in the Northeast and only last 2-6 months, can have serious consequences in local communities, such as agricultural losses, shortages in public water supplies, and low streamflows.

In Ipswich, where average household water usage trails state totals by more than 20 gallons daily, officials are pioneering conservation strategies that could model drought response across the region.

“We’re on the precipice of reimagining what commercial irrigation looks like in a drought and getting to be the first ones to take a leadership role for surrounding communities on a potential solution,” said Rachael Belisle-Toler, Ipswich’s Water Resources Manager.

The town has implemented a range of measures, from rebates for water efficiency to discounted rain barrels and supplies. They’ve also launched creative measures to educate residents about water infrastructure and the effects of climate change, such as book clubs and an exhibit which is currently in the works and will be premiering in April.

“Droughts have been getting frequent and more severe,” said Belisle-Toler. “We have one of the most robust approaches to conservation that I have ever seen for a municipality of this size.”

These efforts align with broader regional strategies such as Sen. Bruce Tarr’s (R-Mass.) North Shore Water Resilience Task Force, which recently broke ground on a $20 million water treatment plant in Ipswich designed to buffer future shortages.

As Massachusetts launches digital tools like the interactive Native Plant Palette, to replace thirsty lawns with drought-resilient species, Belisle-Toler stresses that water equity is a central issue that affects every resident.

“Water efficiency is for everyone,” she said. “You don’t have to be a long time environmentalist. You don’t have to be a scientist. You don’t have to be any specific type of person. Our watershed is connected, and any one individual impact makes a massive difference to people who are even a couple towns away.”

As rainfall and river levels remain at record lows in the region, the crisis underscores a looming question: Can New England’s patchwork of local solutions scale quickly enough to match the destabilizing effects of global warming on our climate?

For Bakal and other farmers, the cost of running a farm, even in drought conditions, is worth it.

To combat the rising scarcity of water, Bakal is using more sustainable agricultural practices such as perennial, drought resistant crops and high tunnels. To support local agriculture such as Twin Birch, they frequently sell their produce at the Rockport Farmers Market and the Ipswich Homegrown Market.

“We had this notion of owning land and growing things to help feed people, and that’s what we did and will continue to do,” said Bakal.