Speaking of high fares and tardiness, will the T have to pay private lenders for being late to deliver its new collection system?

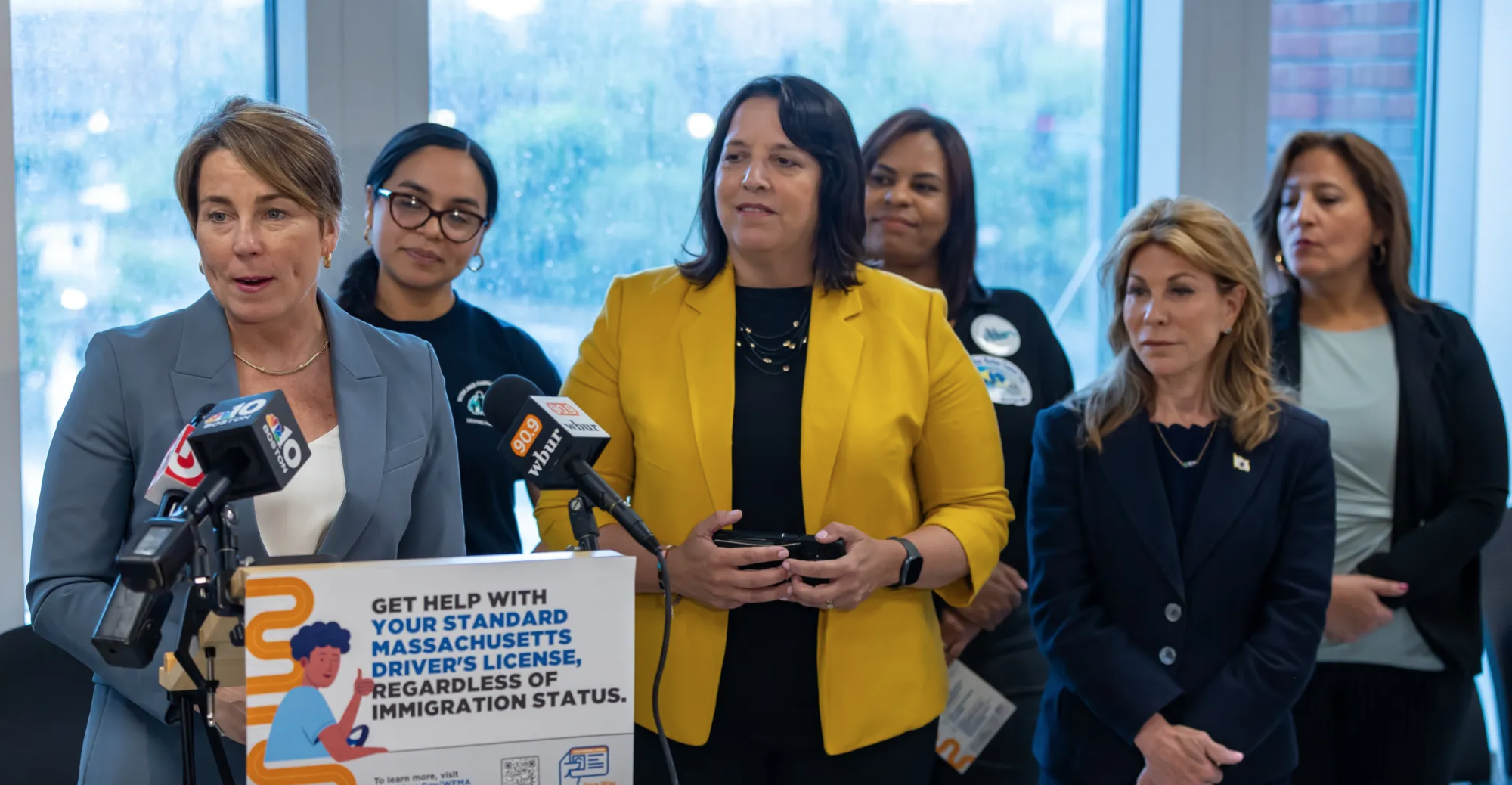

To much fanfare and media coverage last month, MBTA officials announced that their long-planned new T fare collection technology will go online, at least in part, starting this summer.

The system was originally supposed to be running by 2021 at a cost of $700 million. After significant reworkings of the contract between the MBTA and the conglomerate it hired to bankroll and oversee the work in a public-private partnership, the price tag is now close to a billion dollars.

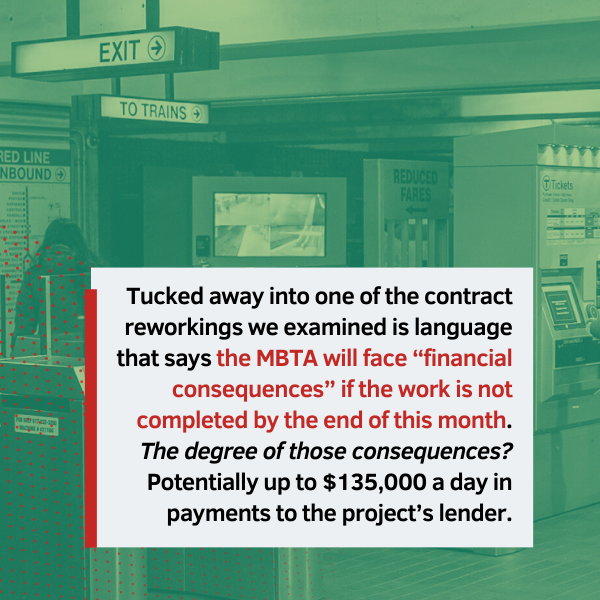

Tucked away into one of those reworkings is language that says the MBTA will face “financial consequences” if the work is not completed by the end of this month. The degree of those consequences? Potentially up to $135,000 a day in payments to the project’s lender.

MBTA officials did not respond to questions about whether those provisions are still in effect after the most recent contract amendment, or if they have been extended to a later deadline. And finances around the deal, already difficult to parse, are even harder to understand now. The entity in charge of AFC 2.0 is a limited liability company created by two massive tech and finance firms, who have since been absorbed by even larger private equity groups.

That means those firms are no longer subject to the government oversight of publicly traded companies—although state lobbying disclosures show that the private LLC they created to handle the billion-dollar MBTA contract has spent $250,000 on Beacon Hill lobbyists.

The finances around the project amount to a “billion-dollar question mark,” according to Stacy Thompson, executive director of LiveableStreets Alliance, a Boston-based transportation advocacy group.

“How much are we actually spending at the end of the day, and what are we getting out of it? This is something the T is continually unable to make clear to the public,” Thompson said. “The finance side is unnecessarily complicated, it’s hard to get answers.”

Thompson and other public policy experts said that while public-private partnerships are often sold to taxpayers as a way for a private company to take on the risk of a public project, the reality is much different.

“This is all public money, there’s a lot of risk that the public sector still retains,” said Shar Habibi, research and policy director for the nonprofit group In the Public Interest. She added that the possibility of the MBTA being liable for additional payments undermines the theoretical lack of risk—and said the private company’s profit incentive means it will be trying to maximize value to itself.

“Their main point in this is to make money; this contract has provisions to make sure they do make money, presumably a lot of money off this,” Habibi said. “The MBTA’s mission should be the provision of a public good to residents. Those are completely different goals.”

Corporate shells

The May 23, 2024 MBTA board meeting laid out the latest change in the eight-year saga of what is known as AFC 2.0. The existing Charlie Card system is Automated Fare Collections 1.0, and the new 2.0 version will go online this summer for buses and subways—excluding the Mattapan Line—where customers will be able to use contactless payments like credit cards and smartphones to pay fares.

It’s a functionality that will ultimately lead to fare inspectors working buses and trains, which civil liberties advocates say could disproportionately target minorities. It’s also a system that has been promised since 2017, when the T hired a national fare collections firm and a British financier to combine their forces for the project, paying most of the costs up front. This kind of public-private partnership is often described as funding, the way a public entity would pay for a project, Habibi said. But it just kicks payment down the road—and jacks up the price.

“It’s a really expensive loan.” The In the Public Interest policy director continued, “They’re not providing funding in the sense of giving money—the MBTA is going to have to pay this back. Developers use that language, We’re giving you funding. It feels less risky than, We’re giving you a super expensive loan and taking control of the asset.”

For this public-private partnership, known as a P3, Cubic Corporation teamed up with the John Laing Group, with Cubic handling construction and operations for the project and Laing providing financing—and that’s where things get complicated.

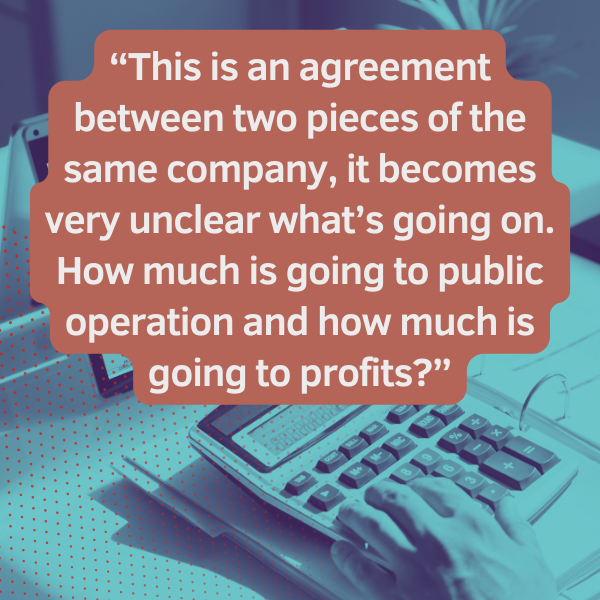

To perform the work, Cubic and Laing created the company Boston AFC 2.0 HoldCo LLC, which is owned 90% by Laing and 10% by Cubic, according to Cubic financial statements. That company in turn created the subsidiary Boston AFC 2.0 OpCo LLC, which is the entity that actually entered into a contract with the MBTA.

OpCo then made its own contract for the design, build, operations, and maintenance of the MBTA’s new system—with Cubic. And John Laing made more than $26 million in bridge loans to HoldCo to kickstart the project. So Laing formed a company and then loaned itself money, while Cubic formed a company and contracted with itself.

These kinds of agreements and company combinations are not unusual in the corporate world—but in this case, Habibi noted, the public is paying for the work, and it can be impossible to track how the money is being spent.

“They’re both [the] financing body and operations body,” Habibi said. “It seems like they’re contracting with themselves to do some of the actual work. This is where it becomes really opaque and becomes really hard to see what is actually going on. … If the operations and maintenance subsidiary is sending invoices to the larger company, who is to say what kind of overhead they’re charging, what profit they’re charging? This is an agreement between two pieces of the same company, it becomes very unclear what’s going on. How much is going to public operation and how much is going to profits?”

‘Financial consequences’

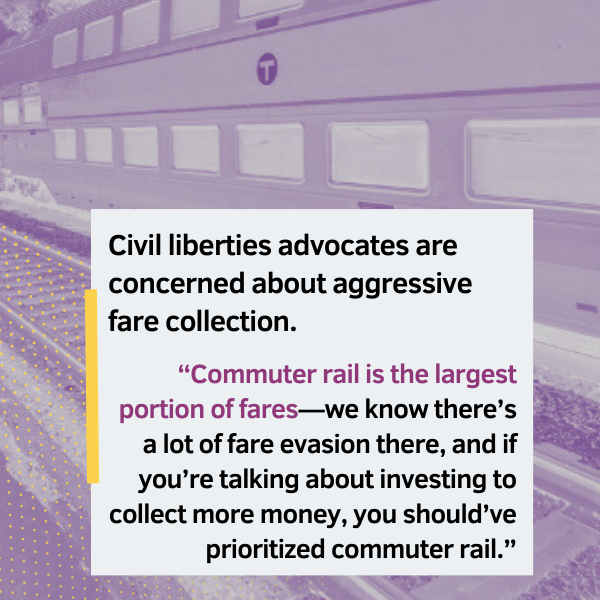

T officials have said they plan to collect $8 billion in fare revenues with the new system, which will be overseen by Cubic—leading civil liberties advocates to wonder in turn if that will incentivize aggressive fare collection. Thompson from LiveableStreets and other public transit advocates have also questioned the idea of developing an expensive fare program for buses in the first place.

“For people who touted this system as a way for the MBTA to do a better job collecting fares, they’re not being smart on return on investment,” Thompson said. “You have to spend a lot more money on equipment you’re putting on buses in order to collect a lot less money. … Commuter rail is the largest portion of fares—we know there’s a lot of fare evasion there, and if you’re talking about investing to collect more money, you should’ve prioritized commuter rail.”

In any case, the path to raking in billions of dollars in fares went awry almost immediately, leading to a massive reworking of the initial agreement two years after it was signed.

That 2018 contract between the T and Boston AFC 2.0 OpCo, the creation of Cubic and Laing, cost $723 million and promised a new system by 2021. But as soon as 2019, it was clear there were major problems. Riders raised concerns about access to cash payment options and demanded more input. T officials disagreed on how fast to bring changes online. An MBTA summary in 2020 refers to “Technical challenges encountered by Cubic,” while a 2019 Boston Globe article is blunter: “the work quickly ran off course because of technological glitches with Cubic fare readers.”

The T re-opened the contract for negotiation in 2019 and by June 2020 all parties had agreed to the “Amended and Restated Project Agreement”—a 3,000-page document laying out the new terms of the deal. Cubic and Laing would be known as the “Systems Integrator” for the AFC 2.0 project.

The new price tag: $935 million. The new due date: June 2024.

The ARPA describes how the T and OpCo can be liable for “compensation events” if they do not live up to the terms of the contract. Seeking to amend the contract at the MBTA board meeting last month, MBTA Chief Procurement Officer Jeff Cook described how Cubic will be held to agreed-on terms—the company will get an $11 million bonus if it fully delivers the system by the spring of 2026. Or, “if they miss it by one day,” Cook said, “they do not get it.”

“The agreement still has metrics,” Cook added. “If they’re not met, they are subject to penalties.”

But what wasn’t mentioned at the May board meeting is whether the MBTA has to meet its own metrics—or face penalties of its own. While the board voted to amend the contract, an MBTA spokesperson said that change order is still being reviewed and not public information. But under the previous agreement, a missed deadline could cost the T dearly.

A 2020 MBTA presentation called “Fare Transformation Overview: Summary of the Systems Integrator Amended and Restated Project Agreement” appears to lay out a major compensation event if that June 2024 due date isn’t met because of something the T does:

“If MBTA action or inaction impedes progress such that the project completion pushes out after June 2024, it can expose the MBTA to financial consequences to compensate the lenders and equity investors. While the calculations are complex, as a point of comparison, in the event of a delay caused by Cubic, the lenders and equity would be entitled to damages of $135,224.78 per calendar day,” a slide reads in part, with the emphasis in the original document. Furthermore, “Sufficient resourcing of all the MBTA disciplines necessary to deliver the project is the single most important step the MBTA can take to mitigate its risks.”

Lenders for the project, according to the Federal Highway Administration, include the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, and MetLife. And John Laing “made loans … totaling $26.2 million in the form of bridge loans that are intended to be converted to equity in the future in accordance with its equity funding responsibilities,” according to Cubic financial statements.

Laing did not respond to a request for comment and a spokesperson for Cubic said the company could not comment due to the terms of its contract with the MBTA. And the MBTA did not comment when asked if that timeline remains in effect, or what damages the MBTA might face. But according to Habibi, the inclusion of the language is worrisome regardless.

“It seems to me that they’re trying to push the risk to the MBTA for project delays,” the nonprofit research and policy director said. Adding, “Even if it’s a lowball estimate, $135,000 a day is not insignificant. … If the delays are due to the MBTA, it becomes arguing between two parties. They are going to try to push as much of this on the MBTA—These delays are caused by you guys, therefore you are subject to all these penalties.”

Private partnership, public risk

Habibi and others said the whole T fare collection situation contradicts the proposed benefits of public-private partnerships like the one between the MBTA and Cubic and Laing. By hiring them, the T let the companies bear most of the cost burden for bringing the system online. At the May 23 meeting, Cook, the chief procurement officer, said the T has paid about $23 million for the project so far.

Cubic and Laing will start getting paid once the system is working. The companies are set to get a series of payments of $105 million, $160 million, and $39 million once the bus and subway system, new Charlie Card system, and commuter rail and ferry systems go online in the next three years, plus more than $70 million a year from fare revenue over the next decade, according to Cook’s presentation at the May 23 meeting.

But the T could potentially be on the hook for even more payments through “compensation events.”

“One of the arguments for public-private partnerships is around risk transfer,” Habibi said. “The argument goes that the private entity takes on more risk and insulates the public entity from risk. … When we see a contract that has a bunch of these compensation events, that the public sector is on the hook for A-B-C-D-E, that risk didn’t actually get transferred. The public sector is on the hook.”

“It’s important for the public to have insight into any major procurement contract,” said Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy for the Center for American Progress. “Unless people know the cost and liability incurred by MBTA and the maximum possible financial rewards to the contractor, it’s impossible to know if the public is getting value for their money. In general, too much information is withheld from the public under the guise of proprietary business information.”

A chart on page 1,358 of the 2020 ARPA provides some information about Laing and Cubic’s financing for the project at the time. It describes $382 million in construction costs—actually building the system—and another $410 million in various financing costs and debt repayments. This drew the attention of the local nonprofit Community Labor United, which issued a severely critical report about the deal in 2022. Using figures in the ARPA, CLU estimated the T could have saved $45 million by using municipal bonds instead of getting higher rates through a P3, and estimated the deal would give Cubic and Laing $288 million in profit and corporate overhead.

“While public finance creates significant costs for the MBTA, private financing can be even more expensive, because typically that financing includes payments to both equity investors and other lenders,” the report reads. “Municipal bonds can have relatively low interest rates because they are low risk to the investor and are often tax-exempt. Private financing does not necessarily have that benefit.”

Private equity, private accounting

The CLU report noted that since the ARPA was signed, financing for the deal has become even harder to follow. Cubic was acquired by private equity giants Veritas Capital and Evergreen Coast Capital Corp., taking them off the public markets and away from stronger SEC oversight—and taking Boston AFC 2.0 OpCo with them.

For example, Cubic had to routinely file reports with the SEC about its finances and projects. Its last quarterly statement, for the period ending March 31, 2021, gives some insight into how Boston AFC 2.0 OpCo was financing its AFC 2.0 work:

“In connection with the execution of the Amended MBTA Contract, Boston OpCo entered into an amended credit agreement with a group of financial institutions (the “Boston OpCo Amended Credit Agreement”), which includes two long-term debt facilities and a revolving credit facility,” the statement reads in part. “The long-term debt facilities allow for draws up to an aggregate of $421.6 million during the design and build phase. The long-term debt facilities, including all interest and fees incurred, are required to be repaid on a fixed monthly schedule commencing once the design and build phase is completed in 2024. The long-term debt facilities bear interest at variable rates of LIBOR plus a margin of 1.75% to 2.0%. At March 31, 2021, the outstanding balance on the long-term debt facilities was $225.3 million, which is presented net of unamortized deferred financing costs of $16.7 million.”

But now that Cubic is under Veritas’ umbrella, it no longer has to reveal that information publicly. And that lack of information dovetails with private equity managers’ philosophy of getting the maximum return out of their acquisitions, rather than supporting the actual business of those acquisitions, analysts said.

“Private equity firms use investor money or debt to take ownership of other companies, using a number of strategies to extract resources before eventually reselling. Cubic’s takeover by Veritas and Evergreen raises concern that corner cutting and understaffing will worsen performance problems and delays for riders using Cubic systems,” the CLU wrote in its report.

And Laing was also scooped up by another private equity giant, KKR. KKR and Veritas did not respond to a request for comment.

“Private equity purchases companies they know they can make money on, usually through internal consolidation,” Thompson of LiveableStreets said. “Private equity didn’t purchase Cubic if they didn’t see that potential for consolidation—that in and of itself should be concerning. … We can’t see how this lines up with other parts of [the private equity groups’] business model that the public may be concerned about. I’m not saying they’re doing something nefarious, but the public has no way of knowing that and that in itself is a problem.”

Habibi agreed: “What’s difficult is that if the company is publicly traded, there are SEC records, even if it’s a very high level. Once it’s private equity you’re dealing with, it is difficult if not impossible to get any sort of info unless they’re handing it out and reporting to the public. … There is this idea that, theoretically, you could have the public entity write into the contract that we need to have this info. Unfortunately, we don’t see provisions in this kind of contract often: Hey, we need you to share this information because it’s important to see where public money is going.”

‘Shady’ lobbying

It’s hard to see the details of OpCo’s spending—but one area is public record.

According to the Secretary of the Commonwealth’s lobbying database, Cubic paid the firm Preti Consulting in excess of $400,000 from 2016 to 2019. Preti is a big player on Beacon Hill, boasting former Senate Minority Leader Richard Tisei among its lobbyists.

Starting in 2019, Boston AFC 2.0 OpCo itself started hiring Preti, paying the firm more than $250,000 through 2023. Records show the company hired Preti again in 2024. Preti did not return a request for comment.

While information beyond that is mostly scarce—OpCo’s interest is listed as “transportation”—the initial 2019 hire has more detail. OpCo hired Preti lobbyist Kris Erickson, who previously worked as chief of staff at the MBTA. According to filings, Erickson’s mission was to “Be instrumental in introducing management and board members to OpCo/Cubic/John Laing staff.”

Some questioned why a company created solely for a contract with the MBTA would need to continue lobbying at the State House—and whether that affected calls for increased oversight.

“It’s shady,” Thompson said. “Everyone has lobbyists, but what exactly does [OpCo] need at Beacon Hill, what are they asking for?”

The LiveableStreets ED added, “We’ve asked the Transportation Committee to call a hearing on this project … it is concerning that there’s all this lobbying going on at the same time we can’t get folks on Beacon Hill to wake up and pay attention to this project.”

MBTA and Cubic officials have hyped the latest promise of contactless payments in the summer as a sign AFC 2.0 is almost complete. But Thompson viewed it as just another shifting of goalposts for an ongoing boondoggle.

“Because it’s so opaque, the T keeps coming back and reframing the project,” Thompson said. “If we are able to offload risk to a private entity but it goes a couple hundred million dollars over budget and is delayed for years, is that a win?

“I struggle philosophically with that as a win.”