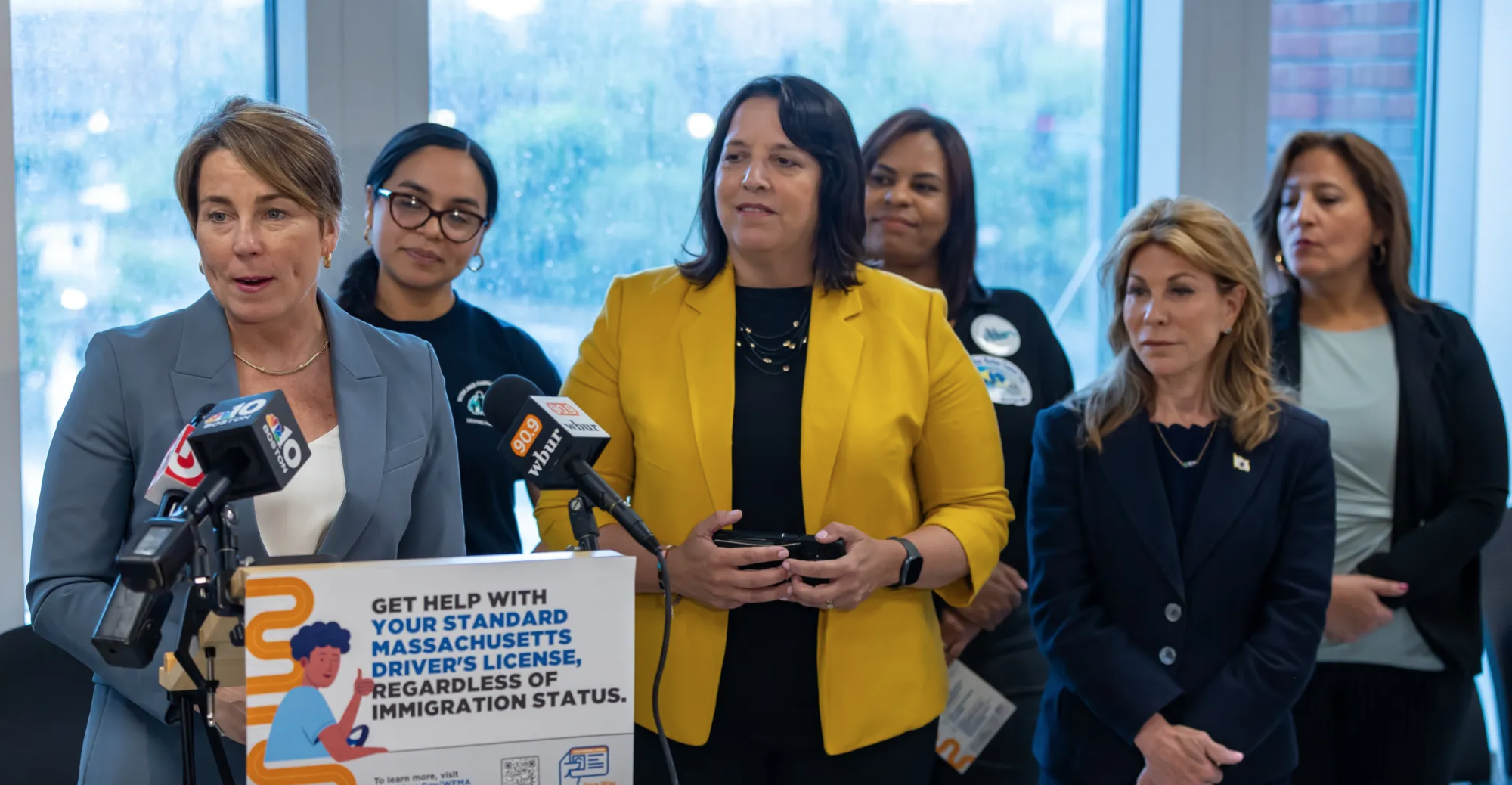

The Massachusetts Parole Board still faces big challenges despite making some improvements this past year. Its final member was approved this week, but is the body equipped to operate efficiently?

At a March 27 hearing on Beacon Hill for the nomination of Rafael Ortiz to serve on the Massachusetts Parole Board, the candidate gave the agency he hoped to join an “A” grade. He never specified exactly why it deserved the high evaluation, but when asked to elaborate, Ortiz said he came to that conclusion “from meeting the Parole Board and from comparing them to the way they were years ago.”

Ortiz was testifying before the Governor’s Council. The elected eight-member body must approve all gubernatorial nominations for judgeships, clerk-magistrate positions, public administrator spots, and members of the Parole Board, among other deliberative positions. For the most part, the council is known for rubber-stamping nominees. Currently the council has seven members; one seat is open since Robert Jubinville became a clerk magistrate in Framingham District Court.

For the past 15 months, the Parole Board has also operated without its full complement—of seven members. Ortiz was nominated by Gov. Maura Healey to fill the seventh slot, and today was confirmed unanimously by the Governor’s Council.

Ortiz, who lives in Worcester, has worked as a juvenile probation officer in Central Mass for more than 30 years. At the hearing, he said that, as a Latino, he has faced racial bias in his community and at work, adding that he looked forward to being on the board and “addressing the glaring racial disparities and bias in the criminal justice system.”

During the late-march hearing, Governor’s Councilor Tara Jacobs expressed disappointment that the governor did not nominate a formerly-incarcerated person for the last spot on the board. Healey already filled two seats: one with social worker Sarah Coughlin, and another with probation officer Edith Alexander. Jacobs was the only councilor who expressed any hesitation about the nominee.

Limping along, the Mass Parole Board functioned with only four members throughout the first nine months of Healey’s tenure. Members face Olympian levels of work—in 2022, they held about 3,000 parole hearings, including 200-plus full board lifer hearings in their Natick office, with the rest held at prisons and houses of correction throughout the state. They decide if petitioners are ready to enter the community and serve the rest of their parole under supervision outside of prison.

In its other role as the Advisory Board of Pardons, the board reviews clemency petitions, including requests for both commutations and pardons—a commutation is a reduction in sentence; a pardon removes the underlying offense from the petitioner’s record.

In a telephone interview for this article, Ortiz said he had attended two lifer parole hearings, watched online hearings for life-sentenced individuals, and read reports to learn about the board and its charge to uphold public safety.

Considering that he has had limited exposure to the board, I asked the applicant why he gave the body such a high grade. He said he based his response on listening to Governor’s Council hearings. He’d heard councilors say that “hearings used to be chaotic.” Ortiz also mentioned the failed nomination of Sherquita Hosang (we wrote about that here), saying, “So many people were against her.” At that time, the board was under the leadership of Gloriann Moroney, now a district court associate justice.

In 2021, we called Moroney’s board “dysfunctional,” citing then-Prisoners’ Legal Services Executive Director Elizabeth Matos: “Parole is not being used as a public safety tool the way it should be.” At the time, pardons and commutations were not being heard by the board, while many in prison who already had hearings were still waiting more than 10 months for a decision. At Hosang’s hearing, Councilor Eileen Duff said, “I honestly don’t know why there hasn’t been a class action lawsuit against the Parole Board.”

From an F to an A?

Lisa Berland has attended 54 hearings for life-sentenced prisoners. In a telephone interview, she said that from her observations, under Moroney, “The board was close to an F. Now, under Tina Hurley, it’s close to a B.”

Berland works with the group Parole Watch (in which this reporter participates) along with 10 to 12 others, and keeps records on the way hearings are conducted and on the kinds of comments board members make to petitioners. She also notes how well prepared those are who seek parole.

Berland sits on the board of directors of the Massachusetts Parole Preparation Partnership (MPPP), a nonprofit which “helps people serving life sentences with the possibility of parole prepare for their parole hearings and live successfully in the community.” MPPP currently has a pilot program with board members inside and outside prison, helping prisoners prep for parole at MCI Norfolk.

Berland said since Hurley took over, the board has “dramatically lessened the amount of time to get a [parole] decision out which is hugely important to people inside.” Decisions are regularly posted on the Parole Board’s website.

According to a report by Gordon Haas, who chairs Lifer’s Group Inc. at MCI Norfolk, the average time people waited in 2023 for their decisions was 86 days. Four and five-year setbacks have also significantly decreased under Hurley, Haas wrote, meaning people wait one, two, or three years to see the board again if they are refused parole. Haas is concerned that written decisions sent to petitioners still do not specify why a parole was not granted.

Berland said that during Hurley’s tenure, the board has started having commutation and pardon hearings, as well as public termination of parole hearings for life-sentenced prisoners. As of Jan. 1, 2024, 13 petitioners successfully had their paroles terminated; between 2019 and 2021, only one had that privilege (and no records can be found of any other lifetime parole terminations). However, Berland said such hearings have slowed considerably since Jan.1. “That could be a capacity issue,” she said, “but we’d like to see a lot more of those kinds of hearings.” According to statute, petitioners with life sentences are eligible to apply after 15 years on supervised parole.

The MPPP board member is also concerned about a lack of transparency “around hearings for prisoners other than lifers.” “The rest,” she said, “are not public or being recorded—although they are supposed to be—and those are the majority.” Additionally, Berland said, “the tenor of the hearings under Moroney was very prosecutorial, and recently, there seems to be a return to spending an enormous amount of time on the original offense”—rather than on the petitioner’s behavior and accomplishments in prison. “I hope it’s not a trend,” she added.

Berland cited a recent hearing where councilors spent more than an hour discussing the underlying crime—the facts of which were not in dispute. This particular hearing was also attended by Attorney Kim Jones, another board member of MPPP, and was one of the first of two hearings where members from MPPP had worked to prepare prisoners for parole, to prove how they have changed during their 15 or more years behind bars.

“MPPP partners do not have to have a legal background,” Jones said by phone. The nonprofit’s materials explain, “Most partners collaborate with parole petitioners to identify potential family and community support for their release on parole, assist with reaching out to potential supporters, identify strong re-entry plans, collate information in support of the individual’s release into a packet to submit to the Parole Board, and help parole petitioners prepare to testify at their parole hearing.”

Both Berland and Jones said that in the aforementioned hearing, the lead questioner spent so much time retracing details of the crime—more than an hour—that, as Jones put it, “the rest of the board didn’t have enough time to go into other aspects of the petitioner’s success.”

The board from behind bars

Shawn Fisher, currently housed at Old Colony Correctional Center (OCCC), earned a positive parole vote on Nov. 29, 2023, three months after his hearing in August. He had served approximately 30 years for the murder of Ralph James Tracey. It was his third time before the board.

Fisher has been cleared to head to lower security at Northeast Correctional Center in Concord, also known as the Farm, but has not yet been transferred, and is thus serving “dead time” at OCCC. In other words, since December, the Department of Correction has not moved him, and he gets no credit towards the nine months in lower security until he actually moves to the Farm. In a phone call, he said that he had asked his attorney to contact the board and see if his time in lower security can be reduced.

Fisher is currently co-chair of the Lifer’s Group at OCCC and wrote to me on the prison email system, CORRLINKS: “The new board seems more focused on the individual and not on who the person was 20+ years ago . . . .What I noticed in my limited encounter may be different from others but for the first time the board was more focused on the ‘what’ and ‘how’ have I changed. In the past, it was more about the facts of a case that were beyond my control to change. I even think there was more recognition toward my victim’s family.”

He added, “I do believe this board is heading in the right direction for the first time in many years although they need help by expanding the board. Even an outsider can see that.” Currently, there is a bill before the Massachusetts legislature to add two more members to the Parole Board: An Act to Promote Equitable Access to Parole, with versions filed by Sen. Liz Miranda and Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa.

“Parole packets are close to a hundred pages thick,” Fisher wrote, emphasizing what goes into preparation. “And with several packets submitted daily [to the Parole Board], no normal person can read that many pages. Not even if it were all John Grisham novels. Common sense has to recognize that.”