Experts Make The Case For More College Behind Bars

College classes cost less than half of what Mass pays to incarcerate people. So why aren’t we educating more prisoners?

“Knowledge of the power structure that runs society has made the biggest difference in my life.”

John Yang was released from MCI Concord in 2020, and is now completing his BA at Emerson College in Boston. In a far-ranging interview, he spoke about being one of four students featured at a March 24 Education in Prison conference at Emerson which aimed to show how and why college programs behind bars need expansion.

“By picking up a book, I was creating a different way of being, finding new strengths and abilities that I didn’t know I had.”

That kind of positive response is common among those who have attended one of the five institutions that offer certificate or degree-granting programs for people incarcerated at Department of Correction (DOC) facilities across the state—Boston College, Boston University, Emerson College, Mt. Wachusett Community College, and Tufts University. All of these programs are funded by the colleges themselves; Yang began his journey through a program known as the Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI). Still, only 213 incarcerated people are currently enrolled in higher education classes across six DOC facilities.

In a 2021 editorial in the Boston Globe, Lee Pelton, the former president of Emerson College who is currently the president and CEO of the Boston Foundation, along with EPI founder and director Mneesha Gellman urged then-governor Baker and the DOC to expand the number of students admitted to college programs and provide more dedicated space for them in prison. “Access to higher education while incarcerated is a lifeline,” they wrote at the time.

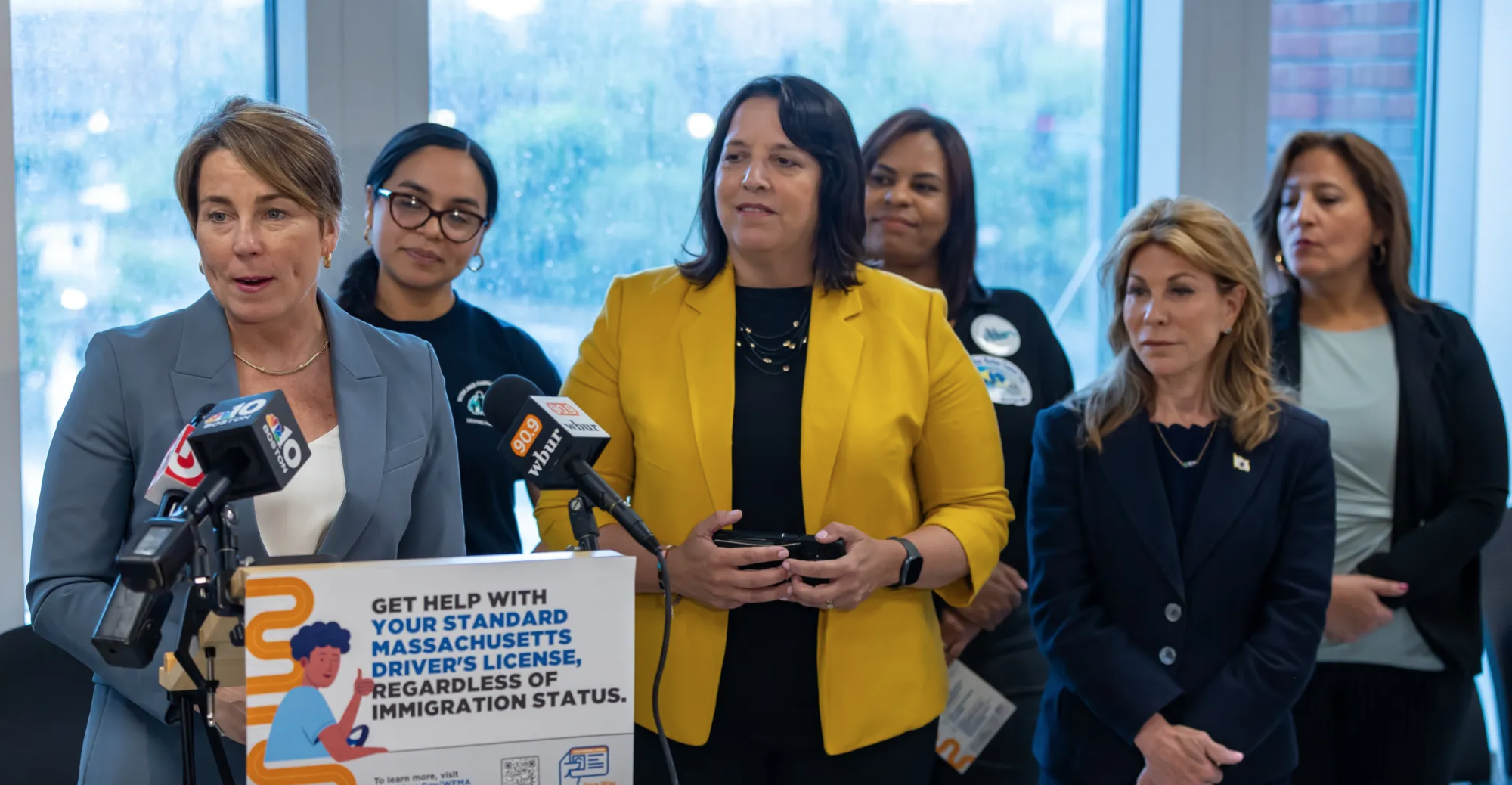

Now, the ball is in Governor Maura Healy’s court. On a panel at the aforementioned March 24 conference, Pelton said, “We need to scale up these programs. … Larger scale provides greater influence.”

The initiative

EPI, founded in 2017, offers courses behind bars and a pathway to a degree in media, literature, and culture, with the same challenging program that would be available to any Emerson student. The goal of college-in-prison programs, says EPI’s website is “to help stop the cycle of incarceration.” Yang said he feels he is no longer at the mercy of the world he was living in before EPI.

In this program, higher ed in prison aims to be as demanding as higher ed outside prison. Yang applied to Emerson through a rigorous admissions process, which whittled approximately 100 applicants down to 20, through essays and interviews. Courses include basics such as Introduction to Literary Studies and Business Mathematics, and unique offerings such as Rainbow Nation: Race, Class, and Culture in South Africa.

After his release to his brother’s home in Fitchburg, Yang got rides to Boston for classes, sometimes staying with a friend overnight in Lynn to make it easier to commute—anything, he said, to keep himself going.

“Someone from my background doesn’t usually have the opportunity or income for this,” he told me, acknowledging the unique chance he’s had with a full scholarship. As of 2021, tuition alone was approximately $50,000 per year at Emerson, whereas as of 2022, per stats from the conference, it cost the state almost $120,000 to house a prisoner in the DOC. Yang was the first in his Concord cohort to transition to “the free world” campus. This fall, he will earn his degree with a minor in nonprofit communication.

The class where Yang learned life-changing lessons, he said, was Power and Privilege taught by Professor Gellman. Speaking to a packed conference audience, the professor, whose father was once incarcerated, quoted a current EPI student in her opening remarks: “We believe the classroom is a sanctuary, Noah’s Ark in hell.”

Why higher ed behind bars?

It is well documented that the more education one has, the less likely they are to return to crime. One of the best known of hundreds of studies on college-in-prison was done by the Rand Corporation and presented at the March conference by Emerson economics professor Sally Moran Davidson. She showed the cost savings and drop in recidivism that results when prisoners receive education while incarcerated.

While Massachusetts lowered its state prison population from 11,403 in 2013 to 6,236 in 2022, costs to house an individual rose in that same time period—from $45,053 to nearly $120,000. Davidson’s graph (below) shows the savings and the low reincarceration rate for those who get a college education.

![]()

A 2022 position paper by the Boston Foundation, Unlocking College: Strengthening Massachusetts’ Commitment to College in Prison, notes “college in prison reduces the likelihood of recidivating by nearly half (48 percent).” The paper, signed by 22 notable advocates including college deans and presidents, also mentions how other states—in particular, New York, Connecticut, and California—have invested more fully than Mass in higher education behind bars. In addition, the report points out that while such programs increase critical thinking, improve racial inequities, develop personal power and mental freedom, and are “recidivism reduction tools” for reentry, they are also “valuable for those with very long sentences and even those who might never go home.” The report urges the commonwealth to “enroll students irrespective of release dates … to foster a community of healing within prisons.”

The Boston Foundation points out that since the 1970s, Mass higher-ed institutions have awarded 487 degrees or certificates to incarcerated students in the Bay State. However, most of those degrees and certificates were awarded before the 1994 Crime Bill banned people in prison from accessing federal need-based financial aid for postsecondary education. Privately funded institutions then became the only route to higher ed behind bars.

After the crime bill

Mac Hudson, one of the other four EPI panelists on March 24, was an angry kid when he was sent to Walpole (now MCI Cedar Junction). But in 1994, he had an epiphany while locked in the notorious Department Disciplinary Unit (DDU). Another term for solitary confinement, the DDU allowed Hudson only one hour a day out of his cell. His mother said to him, Son, don’t you think when they have to keep locking you up inside a prison, something is wrong? Then things began to change. Hudson started reading, discovering that books could help him transform himself and the conditions he found himself in.

That was the same year when the country was aflame with fears of rising crime, and President Bill Clinton signed into law the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. Current President Joe Biden has since apologized for his role in enacting the legislation, acknowledging that it was a “mistake” that increased mass incarceration for people of color.

The law authorized the death penalty for 60 new federal offenses and, according to the Center for American Progress, added “a mandatory life sentence for individuals with three or more felony convictions,” and “levied harsh new penalties for justice-involved youth.” It also had a little-known provision taking away Pell grants from prisoners.

In 1994, nationwide, there were 772 schools offering college programs to people in prison. Those programs were funded by Pell grants, a form of need-based federal aid for college students. Some argued that awarding Pells to prisoners was taking away grants from those outside of prison, but in reality, fewer than 1% of awardees were incarcerated in 1993 to 1994. By 1997, after the Clinton bill went into effect, only eight programs remained. Prisoners like Hudson were locked out of college.

In 2016, under President Barack Obama, the US Department of Education renewed its commitment to allowing prisoners to access state aid through Pell grants by announcing Second Chance Pells. According to the Vera Institute, a partner in the fight for Pell restoration, this was put into law in 2020. By the summer of 2023, Vera reports up to 463,000 people who are currently incarcerated will be eligible for aid. That means many more universities and community colleges will be able to get back inside. But as the Boston Foundation points out, “the impact of Pell restoration has yet to be seen, as [is] the quality control on how it is implemented, through what types of programs, and with what oversight.”

By the time Hudson got to EPI in 2017, he was a self-taught man and a prison lawyer, he said in a phone interview. He had even won a few cases from behind bars, including Hudson v. Dennehy, winning the right to Halal meals for Muslim prisoners. He began classes at Concord, but when he earned parole in 2021, he went first to serve “pre-release” time at a lower-security facility, Northeast Correctional Center (or the Farm), across from MCI Concord.

“I had to raise hell to get education there,” he recalled. Hudson took one class at the Farm before he was released on parole. Now, he works full time at Prisoners’ Legal Services (PLS), an organization serving people who are incarcerated. Between 2006 and 2022, he was an inside liaison on the PLS board; now, as the org’s community liaison coordinator, he “organizes events, builds community awareness, and tries to insure access to Black and brown people behind the walls,” he said.

Hudson, meanwhile, is currently taking four classes at the Boston campus. In May, he will be the first from the Concord EPI cohort to graduate.

Scaling up

An afternoon panel at the Education in Prison conference attempted to answer how scaling up could occur. Lee Pelton, state Sen. Jamie Eldridge, state Rep. Mary S. Keefe, and former state Sen. Sonia Chang-Díaz discussed building a network and the need for more dedicated space for education in these institutions, and emphasized that students should be able to tap into college programs if they transfer from one prison to another. All agreed with Sen. Eldridge that “higher education programs should be welcome at all institutions.”

According to Unlocking College, if Mass hopes to take advantage of the restoration of federal funding for college behind bars, the new governor needs to make college programs a priority. To quote the report, “Giving people a reason to invest in themselves—an opportunity many in the prison population have not had before—can alter the value they put on their own life and the lives of others.”